At the dawn of the 21st century, Netflix was a small company mailing out red envelopes, The Sopranos was new, AMC was short for American Movie Classics, and reality TV was going to steamroll every other form of television. Survivor debuted in 2000. Nearly 52 million people watched its first finale, kicking off a craze for the format that led to American Idol, Big Brother, The Amazing Race, The Bachelor, and less enduring experiments now lost to the sands of Wikipedia. Reality TV was cheap, easy to make, and popular. Scripted TV was expensive, laborious, and not popular enough to make up for being so much less cheap and easy than reality TV. Scripted television was a dinosaur and reality TV was its meteor.

A decade and a half later, scripted and reality TV have switched roles, and we need another provisional metaphor: Scripted TV is the tortoise and reality TV is the hare. Scripted television is #peaking and, as Vulture’s Joe Adalian pointed out in a piece on the diminished state of reality television, neither the networks nor cable has been able to create a reality smash in years. The most successful network shows have been on for over a decade, and while the Kardashians keep truckin’, nothing has replaced the likes of Duck Dynasty, Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, or Jersey Shore at the watercooler.

Reality TV’s flagging fortunes may be due to the cyclical nature of taste, fatigue with the format, reality shows’ resistance to binge-watching, TV’s consumption model du jour, or some combination of all three. One can binge on a reality show, but as Mark Harris put it for Grantland, “watch four episodes of a reality-competition show in a row and I think that, with surprisingly few exceptions, you will want to die.”

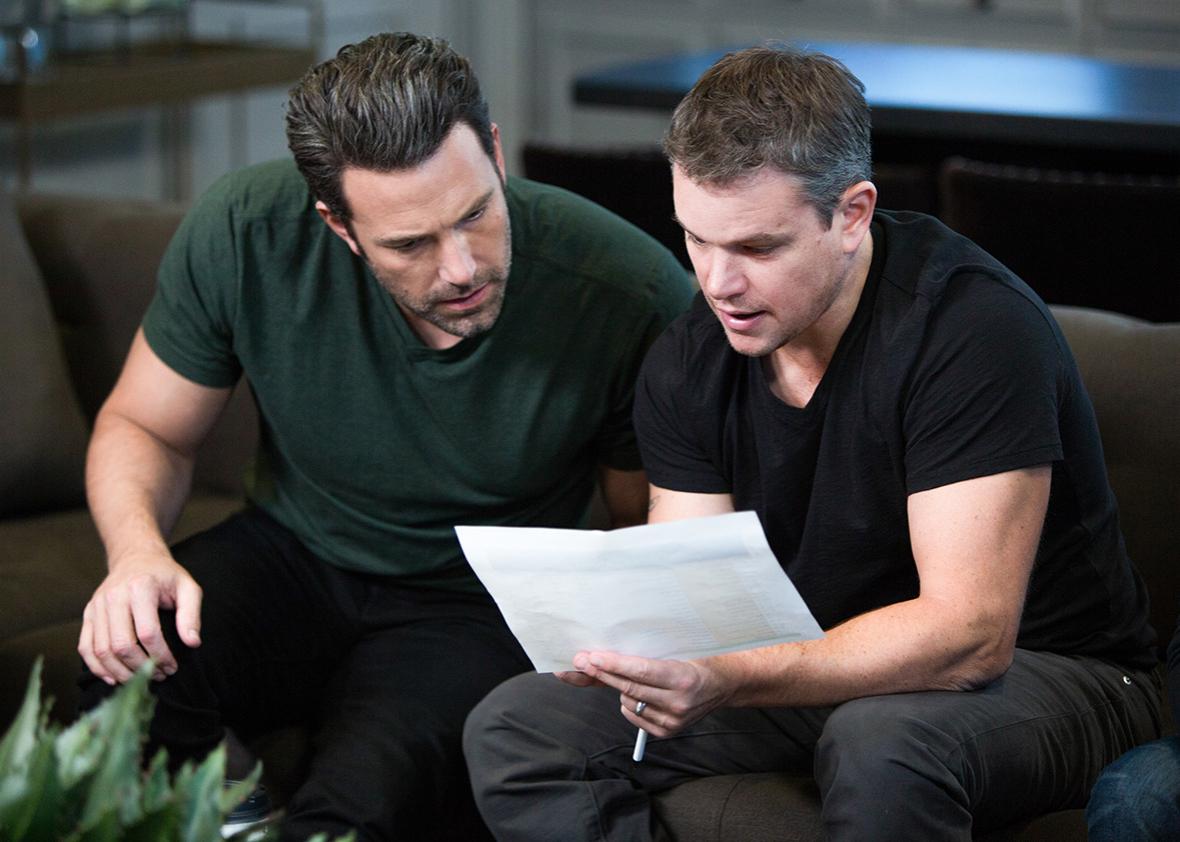

Project Greenlight, currently in its fourth season on HBO, is one of those exceptions. The series, produced by Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, in which a young director is given the funds to make a movie of Damon, Affleck, and HBO’s choosing, aired its first three seasons between 2000 and 2005. Each resulted in a decent TV show and an execrable film. Project Greenlight returned after a decade with a renewed dedication to hiring a director who might plausibly make a decent movie, or at least that’s what I gleaned from the decision to hire gangly cinephile Jason Mann, an Edward Gorey illustration come to life, even after he walked into his interview and negged everyone there by expressing distaste for the existing script. (It was during the interview process that producer Effie Brown called attention to the extreme whiteness of the potential directors and was condescendingly, and unconvincingly, told by Damon that on-screen diversity is what really matters.)

As Harris explained, this season has been primer on the “death by a thousand cuts” that can eventually compromise a film. In the first episode, Mann described his aesthetic as an avoidance of moments that feel too movielike, too familiar, too rote, too cliché. A few episodes later, he had filmed both a pillow fight and an incorrigible character drawing penises on another’s sleeping face, activities that are as movielike as they come—existing, for the most part, only in movies.

But Project Greenlight has also been a primer on reality TV’s best quality: the way that it can capture unspeakably complex human relationships in all their unspeakable complexity. However orchestrated and fabricated a reality show may be—however not “real” it is—it can also get at interpersonal dynamics in a way that scripted dramas can’t, because it, like life, is full of the sloppy, contradictory, chaotic, subliminal behaviors of people who believe themselves to be the center of the story, no matter the title of the show.

The particular relationship I speak of is the one between director Jason Mann and producer Effie Brown. If one were casting a drama, one would have to be more subtle in creating antagonists. Effie is a black woman experienced in making small-budget features. Jason is an inexperienced white man who has never before made a movie with other people’s money. Their dysfunctional rapport can be seen as a referendum on race, gender, privilege, and entitlement. It can be taken as a commentary on creativity, vision, flexibility, and compromise. It can be used as an explainer on the hierarchy of a movie set. It can be understood as an examination of two very particular people’s very particular personalities banging into each other like pots and pans. The best thing about Project Greenlight is that you should read it all these ways at once.

The root conflict between Effie and Jason seems to me to spring from a fight about whether the movie should be shot digitally or on film. From such concrete beginnings a psychological aria has arisen. Jason, a dedicated cineaste, was hellbent on using film, though it is more expensive and rare. Effie, who has worked on many films shot digitally, was sure she could convince Jason to do otherwise. Stubborn, meet stubborn. As the line producer, Effie is in charge of the budget, and she first tried to convince Jason that digital could look just as good as film. When that failed, she proceeded as if using film was not even a possibility. But Jason was not to be denied, eventually going to Affleck, who secured some more money from HBO for Jason to shoot on film, at the cost of losing two shooting days.

In this situation, was Jason behaving like an entitled white man who refused to compromise on something he should have? Or was Jason behaving like a director who refused to compromise on something integral to the movie? And how can you tell when entitled white man and director so obviously share a skill set? Was Effie acting like a line producer or a line producer irked that her director wasn’t behaving like a malleable rookie? Was she so irritated by Jason’s stick-to-itiveness because he wouldn’t compromise or because he ignored her authority? And did his ignoring her authority feel more disrespectful because he is an inexperienced white man?

This was only the beginning. Effie has grown increasingly aggravated with Jason’s entitlement and his obliviousness, his lack of gratitude and appreciation, the way his pickiness (or is it perfectionism?) puts stress on everyone else on set. But what looks to her like ingratitude could just be focus and inexperience. What looks to her like entitlement could just be social awkwardness and a bad habit of judging people too soon. It could also just be directing. (“I always worry about directors who are too agreeable,” Affleck said when he visited set.) And whether Jason is an ingrate or a weirdo, decisive or plain clueless about how a budget works, perhaps he is picking up on the way Effie jumps to say no—to film, to a Farrelly brother acting as Jason’s mentor, to roller skating on set—not just because she has to, though she often does, but because she wants to teach him that he can’t always get what he wants. At the very end of the shoot, after a stunt had gone poorly, Effie wondered if Jason now regretted giving up those two extra shooting days. She’d been keeping score.

I could go on. There’s no interaction the two have had that doesn’t merit dissection. Even their lack of interaction rewards examination. Effie is regularly spun out by Jason. Jason almost seems like he has to be reminded that Effie exists. Run that through lenses of race, gender, job description, and personality.

Reality TV has always inspired hand-wringing and temperature-taking: Can America really be healthy if it wants to watch Survivor, Joe Millionaire, Paula Abdul, the Situation, or the Kardashians? But now that reality TV has been revealed not as some malignant mind fever but another genre of entertainment, as great or foul, good or bad, watchable or unwatchable, as any other, let’s appreciate when it gets this deep.