Read all Slate’s coverage of The Jinx.

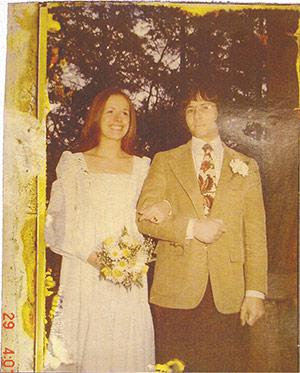

In 2010, Andrew Jarecki—the documentary filmmaker responsible for the disturbing, brilliant Capturing the Friedmans—made his first fictional feature: the not particularly well-received All Good Things. The movie starred Ryan Gosling and Kirsten Dunst and was based on a true story, the 1982 disappearance of Kathleen Durst. When she vanished, Kathleen was a 29-year-old medical student married to Robert Durst, a scion of a New York City real estate fortune. Her disappearance became tabloid fodder, but in the absence of a corpse or a crime scene, the police believed that she had skipped out on a bad marriage, even as Kathleen’s friends and family became more and more convinced that her husband had murdered her. As the years passed and Kathleen failed to appear, Robert Durst became the only suspect—even more so after the execution-style death in 2000 of a friend with possible knowledge of the crime—but no charges were filed against him. Then, in October 2001, Robert Durst was arrested for the murder and dismemberment of a man in Galveston, Texas.

Jarecki wanted All Good Things to be a relatively balanced film, a movie that, he says in The Jinx, “Robert Durst could sit and watch and have an emotional reaction to.” He seems to have accomplished this, because soon after the film’s premiere he got a phone call from the real Robert Durst, who, for the first time, agreed to sit down and be interviewed at length. Thus was born The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, a fascinating, unsettling six-part documentary premiering on HBO this weekend. It’s the latest true-crime story to unfold with all the narrative force—and narrative devices—of fiction. Like Serial and the riveting true-crime documentary The Staircase, The Jinx metes out information like a time-release capsule, turning each episode into a series of revelations and the audience into detectives. But The Jinx, as perhaps befits the substance of a true-crime story, has a grotty kick: Close proximity to Robert Durst is exactly as disquieting as you would expect close proximity to a probable murderer to be.

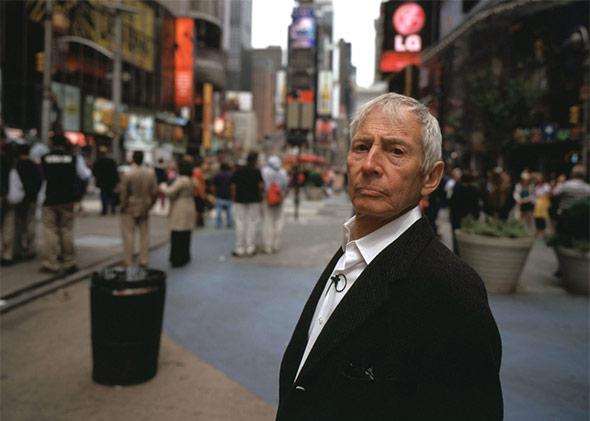

Courtesy of HBO.

Superficially, Jarecki plays his opinions about his subject close to the vest. The Jinx does relatively little of the step-by-step emotional hand-holding that Sarah Koenig did for the audience of Serial. Instead of mellifluous asides, Jarecki does his signposting with the deployment of various narrative conventions. Durst is presented as an extremely suspicious character. The series begins not with Kathleen’s disappearance, but rather a torso washing up on the shore in Galveston. The police methodically trace it back to Durst, to whom we are introduced almost exclusively through the eyes of others using interviews, archival footage, and some overly beautiful restagings.

The picture of Durst that emerges from cops, lawyers, Durst’s brother, and Durst’s second wife is unflattering and odd. The case against him seems airtight. An officer, explaining to Durst his bail, asks if he has $250,000. “Not on me,” Durst replies. He apparently cross-dressed as a deaf-mute woman to avoid attention from the police. He steals a hoagie while he has $37,000 in his car. His brother felt compelled to hire a bodyguard to protect his family from Robert. In an interview from that time, Durst denies he would cause his brother harm, while noticeably smirking. It is only after all of this that The Jinx jumps forward to Durst’s call to Jarecki, and we learn that the substance of the series will be an interview with Durst, as he makes a more chronological accounting of his alleged crimes, starting with Kathleen’s disappearance.

There is a narrative necessity to this setup. A guilty man’s being in jail, like an innocent man’s being out of it, is not a particularly high-stakes starting point. Only in the possibility that something has gone seriously wrong with the criminal justice system does a story like The Jinx take on urgency. (This is why, among other reasons, both Serial and The Staircase began with the implication that their protagonists were innocent, before complicating things.) Robert Durst is currently a free man who was never tried for the disappearance of his wife. The dictates of building narrative tension insist The Jinx at least begin by viewing him with suspicion.

But Durst is also, to put it in scientific jargon, a hella creepy free man. This is, obviously, a highly personal evaluation, but so much of the pleasure and passion of true (and fictional, for that matter) crime comes from mastering facts to defend exactly these personal determinations. Durst, his skin almost translucent, blinking like a baby, and matter-of-factly admitting his alibi for the night of Kathleen’s disappearance was completely made-up, seems bone-chillingly off. The Jinx, while maintaining the façade of a certain kind of neutrality—Jarecki says he didn’t want to “walk into [the interview] with very strong assumptions”—has to take into account what I, unhumbly, assume will be a fairly common reaction to Durst: five-alarm stranger danger.

There is something inherently unsavory about true crime, the way it turns a murder into a story we can debate at dinner parties and on Reddit and Twitter. In both true and fictional crime stories, the victim gets overshadowed by someone else, a detective or a murderer, by Sarah Koenig or Adnan Syed, by Rust Cohle or the Yellow King. No matter how seriously a project takes the victim and her absence, there is no substitute for presence. Syed, The Staircase’s Mike Peterson, and Robert Durst are much more fascinating and tangible than the women they may or may not have killed simply because they are alive, and we can hear their voices.

The Jinx accentuates the fundamental ickiness of this imbalance, which makes it both less thrilling and also, perhaps, less ideologically off-putting than its aforementioned predecessors. It’s a drag to consider, but should learning about a murder be fun? True crime often makes it so. The Jinx tries to purely entertain at times. It has an opening credit sequence with a rousing soundtrack that could belong to a scripted series, and it restages some of Durst’s memories with uneasy glamour. But through the first two episodes, all that HBO sent out for review, Durst makes for such eerie company that it is hard to forget the horrifying circumstances that have brought him to our attention—and difficult to engage in the internal back and forth about guilt or innocence that makes true crime so absorbing, even as it renders the victim an afterthought. The Jinx is as unnerving as it is engrossing, and that’s exactly as it should be.