If Finding Nemo, ostensibly the story of a widowed clownfish’s search for his missing son, was in fact a canny parable about the joys and anxieties of parenthood, its 13-years-later sequel Finding Dory explores—in Pixar’s typically whimsical, jewel-toned, sight-gag-stuffed fashion—an entirely different existential condition of adulthood: the grown-up child’s quest to reclaim and understand his or her ever-receding past.

This delightful new movie’s heroine, a blue-and-gold surgeonfish voiced to perfection by Ellen DeGeneres, played a supporting (albeit crucial) role in Finding Nemo. Dory’s breezy inability to retain new information for more than a few seconds at a time served, in the original film, primarily as a source of comic relief in contrast to the high-strung and micromanaging fish-dad Marlin (voiced by Albert Brooks). As they navigated the perils of the open sea beyond Marlin’s cozy home reef, he operated at a constant slow boil of very Albert Brooksian frustration over his unflaggingly cheerful sidekick’s short-term memory deficits. Though it must be said that Dory’s courage and openness to experience also permitted the risk-averse Marlin to embrace crazy rescue-mission tactics he would otherwise never have dared to try.

But Nemo—directed and co-written like its follow-up by Pixar regular Andrew Stanton, who also co-wrote and directed Wall-E—never stopped to ask why Dory’s thought processes operated so differently from those of the marine life surrounding her, or how she might have come to be a lone, wandering fish with enough time on her fins to drop everything and join Marlin on his quest. Finding Dory furnishes the forgetful surgeonfish with an origin story—a pair of words that may strike fear into the hearts of understandably sequel-weary audiences. But the way Stanton expands on the nature of Dory’s condition and subtly connects it to familiar land-based phenomena, such as the existence of differently abled brains in our own human world, means that Finding Dory often goes, if you’ll forgive the maritime metaphor, to a level a few fathoms below the cruising depth of its much-loved predecessor.

What it lacks in originality and narrative momentum—even more than Nemo, Finding Dory is in essence a loosely connected series of comic-suspenseful chases, bookended by heart-tugging moments of family separation and reunion—this new movie makes up for in psychological acuity and sensitivity. For the first time, starting with the very first scene, Dory’s tendency to slip in and out of a state of distracted oblivion is presented not as a personality quirk but as an inborn cognitive challenge, one that her parents (lovingly voiced by Diane Keaton and Eugene Levy) attempt to compensate for by teaching baby Dory (an adorable Sloane Murray) various tricks for not losing her way. “Just keep swimming, just keep swimming,” her mother reminds her, in a made-up chant of encouragement Nemo viewers will remember as the adult Dory’s mantra in times of trouble.

But when little Dory forgets her parents’ repeated admonishments to steer clear of the violent undertow that rushes past their seaweed-protected cove, she’s washed away into the vast, lonely ocean, where her inability to recall any particulars about her home or parents dooms her to an early life spent navigating the perilous depths on her own. Her solitude is underscored by a recurring image of Dory as a tiny blue figure floating, almost indistinguishable, against a background of endless deeper blue. Finally, in a scene that recreates line-for-line her first encounter with the distraught Marlin in Finding Nemo, Dory gains a purpose, a home, and a kind of second family.

Fast-forwarding to one year later—thereby skipping over all the action of the first film—we find Dory living happily next door to the snug anemone shared by Marlin and Nemo, now voiced by Hayden Rolence. (Alexander Gould, the young actor who played him before, has long since aged out of the part.) But some part of Dory still retains fleeting memories of the loving home she left so long ago, and Marlin reluctantly finds himself and his son accompanying her on a second journey across the open ocean. This time, they’re headed for the fictional Marine Life Institute in Morro Bay, California (an ecologically correct facility clearly based on the Monterey Bay Aquarium), where Dory believes she can finally locate her long-lost parents.

Once they’ve hitched a ride across the sea aboard the shell of surfer-dude sea turtle Crush (voiced here, as in Nemo, by writer-director Stanton), Dory and her companions are separated by chance. Marlin and Nemo make the acquaintance of some new marine wildlife, including a pair of lethargic sea lions voiced by Idris Elba and Dominic West. (There’s something wonderful about imagining The Wire’s Stringer Bell and Jimmy McNulty granted a second life as pinniped best buddies, sunning themselves all day on a toasty rock.) Dory, having been scooped from the sea by workers from the institute, is eventually befriended by a nearsighted whale shark (voiced by Kaitlin Olson) and an underconfident beluga whale (voiced by Ty Burrell).

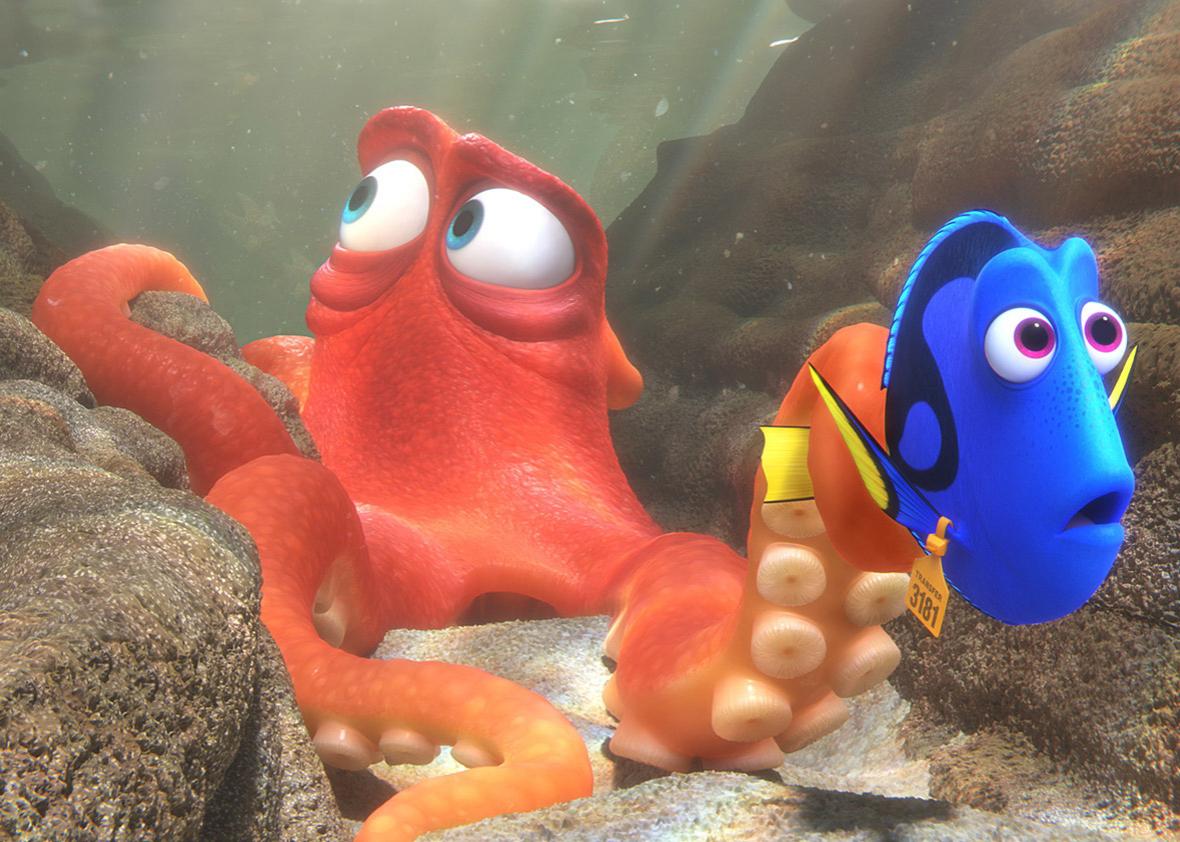

My favorite new character may be the misanthropic octopus Hank (voiced by Ed O’Neill), who uses his camouflage skills and ability to survive for brief periods out of water to help ferry Dory—whom he carries around in whatever receptacle is available, from coffeepot to child’s sippy cup—from one part of the institute to another, looking for anything to trigger her dependably spotty memory. (Hank gets a well-earned curtain call during the credits, and another instant fan favorite comes back for an encore after they’re over, so be sure to stick in your seat.)

Finding Dory is more squishily plotted than the drum-tight Finding Nemo, and some parents may find the middle section—an escalating series of antic chases through various spectacularly rendered aquarium exhibits—a tad repetitive, though I doubt the under-12 set will notice or care. There are more octopus-camouflage sight gags than you can shake a tentacle at (though none more amazing than the quick-change abilities of real-life cephalopods), and a climactic freeway chase sequence involving echolocation, the soothing recorded voice of Sigourney Weaver, and a pack of sea otters so adorable their snuggling can be effectively weaponized.

But even at its silliest and most action-packed, Finding Dory never loses sight of its emotional center: that deeply human (and, apparently, piscine) desire to understand where one came from and to reunite with the creatures one loves best. Without giving the ending away, I can say that Dory’s final fate is both a vindication of her drive to go home and an affirmation of her ability to succeed not just in spite of, but because of, her weird and wonderful sieve of a brain. That resolution is enough to send viewers out of the theater afloat in a small salt-water sea of their own making.