I predict that The Dictator (Paramount) is the movie that will siphon off the casual Sacha Baron Cohen fans from the hardcore ones. People who spent the fall of 2006 quoting lines from Borat about “making sexytime,” then found themselves laughing hollowly through the singing-penis scene in Brüno, may decide they’re through with the boundary-ignoring British comedian after this half political farce, half romantic comedy. For one thing, the stunt aspect of those first two films is absent for the first time. The Dictator is a fully scripted comedy (the screenplay is by Baron Cohen, Alec Berg, David Mandel, and Jeff Schaffer) with none of its star’s signature ambushes of unsuspecting public figures. This robs the movie of that anarchic, anything-could-happen energy that animated the first two features.

The Dictator also represents the moment in which Baron Cohen runs up against the limitations imposed by his own abrasive persona. I think it’s safe to say that he has no equal as an un-embarrassable guerilla satirist, but for that very reason, he’s an odd fit as a romantic hero. The conventional meet-cute love story at the center of The Dictator (a North African tyrant in hiding falls for a crunchy Brooklyn peace activist) feels like a bizarre concession to some nonexistent demographic that prefers its sick black comedy with a side of humanist sentiment. Isn’t the whole point of going to a Sacha Baron Cohen movie to get away from humanist sentiment, to go to a place where darker regions can be accessed?

In The Dictator’s early scenes at least, some of that darkness is on view as we get a vision of what life is like in the fictional country of Wadiya, over which Adm. Gen. Aladeen (Baron Cohen) rules with casually capricious brutality. Aladeen orders a weapons engineer’s execution because the engineer refuses to make the nuclear missile he’s developing sufficiently “pointy,” and Aladeen wins multiple medals in the Wadiya Olympics by shooting his competitors dead during the race. He substitutes his own name for many important words in the language, including both “positive” and “negative” (leading to some confusion vis-à-vis HIV test results). The obscenely wealthy Aladeen also flies celebrities to his lavish palace for a night of sex (a Polaroid wall of his conquests reveals past visits from Lindsay Lohan, Halle Berry, and Oprah Winfrey), then begs them in vain to stay for a cuddle.

The movie veers away from political satire in the middle section, as Aladeen travels to New York, intending to deliver an Ahmedinajad-style rant at the U.N. Instead, the Wadiya resistance kidnaps him and begins training a feebleminded lookalike double (also played by SBC) to read a statement promising democratic reforms. After escaping his captors, Aladeen holes up at an organic grocery store in Brooklyn run by hippie bleeding-heart Zoey (Anna Faris.) The two gradually fall in love, despite Aladeen’s near-nonstop awfulness (in addition to being a font of anti-Semitism and racial hate speech, he kicks one customer’s loudmouthed son and delivers a couple’s baby on the store’s floor, only to tell the parents, “Bad news. It’s a girl. Where’s the trash can?”)

“It’s a girl. Where’s the trash can?” did elicit a hoot of shocked laughter, though the critique of sexism implicit in that line is undercut by the carefree misogyny of many other scenes in which Aladeen mocks the unglamorous (but adorable) Zoey for being a “lesbian hobbit” who should shave her underarms and lose five pounds. Most of The Dictator had me neither laughing nor shocked, but just staring at the screen in anxious is-that-all-there-is? silence. The movie has a deadening sluggishness at its center, a sense of exhausted shtick on Baron Cohen’s part and missed opportunities for the supporting cast. Anna Faris, Ben Kingsley, and John C. Reilly, all gifted comic actors, do little more than drift in and out to set up punch lines. (As Aladeen’s always-about-to-be-executed right-hand man Nadal, Jason Mantzoukas does get off a few agreeably deadpan jokes.)

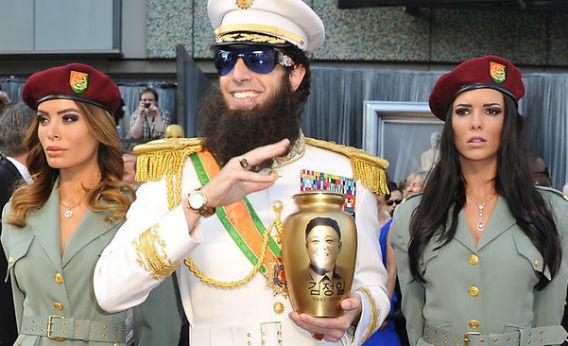

Though each of his movies so far has shown diminishing returns, Baron Cohen hasn’t lost me entirely; in fact, I’m eager to see where his career goes next. As a performer, he’s a transfixing enigma, with a monklike commitment to the repellent characters he creates (his resistance to appearing in public as himself runs deeper than just showbiz pranksterism, I think) and a near-superhuman tolerance for social opprobrium. He’s also an agile physical comedian, as he showed in a Peter Sellers-like bumbling-cop role in Hugo, and can even put over a Sondheim song, as he demonstrated in Sweeney Todd. At their best, Baron Cohen’s puerile provocations can tap into deep wells of desire, envy, and shame—the audience laughs because he does things so awful we’d never dare to try them. Now if he would just try doing something he’s never done before.