Last week, video of Black Lives Matter protesters in Cleveland made the rounds, and they were chanting the chorus to one of the most acclaimed songs of 2015 so far: “We gon’ be alright! We gon’ be alright!”

The song is Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” from his sprawling, topical masterpiece To Pimp a Butterfly, and I’m surprised it took this long for it to be used during a protest. (Or at least, for it to be caught on camera and made viral.) The chorus is simple yet extraordinarily intoxicating, easy to chant, offering a kind of comfort that people of color and other oppressed communities desperately need all too often: the hope—the feeling—that despite tensions in this country growing worse and worse, in the long run, we’re all gon’ be all right. And more than that—the specific kind of comfort that comes from repeating that line over and over. When protesting police brutality and police duplicity—when reminding the authorities and the watching world that we can survive this, too—what more timely, relevant chant could there be?

I’ve been returning to this song again and again this spring and summer. In part that’s because “Alright” is just damn good ear candy, with its breezy Pharrell-produced harmonies, its swinging, laid-back production contrasting with Lamar’s skittering wordplay. But I also listen to it because it’s been a long and difficult year since Ferguson, and the world sometimes seems like a terrible place, and I need Lamar’s reminder that we’ve been down before. Another black person shot by police? Turn on “Alright.” A young black teenager’s graduation party turns into an unnecessarily horrifying police encounter? Turn on “Alright.” A white supremacist murders black church members during a prayer session? Guess it’s time for “Alright.” A black woman found hanging in her jail cell under suspicious circumstances? Well …

I’m not alone in this. Just in the past few months I’ve attended dance parties in which the majority of the attendees were people of color. When “Alright” comes on, the sense of community in the room has been astounding, people exuberantly shouting the chorus in a way that echoes that of those protesters (though obviously, under radically different circumstances). On a recent episode of the BuzzFeed podcast Another Round, co-hosts Tracy Clayton and Heben Nigatu discussed the power of the song at this moment, with Clayton saying she also turned to it when things in the news made her sorrowful. In a blog post for Very Smart Brothas, Jozen Cummings wrote about “things we can’t do while black,” including: “Listen to some song about being in love or being happy without listening to Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Alright’ first.”

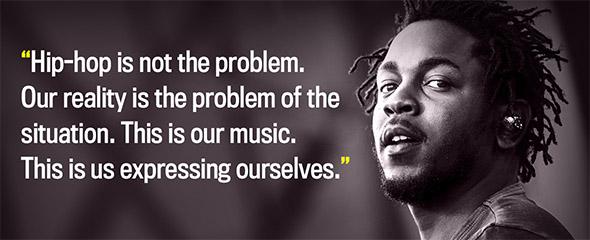

Lamar clearly means for the song to echo across the news of the summer. His late-June performance at the BET Awards, perched atop a police cruiser, American flag waving behind him, seemed to be making a kind of argument for the role the song might play in black communities and black protests. When Fox News unsurprisingly attacked this unflinching stage performance—“Hip hop has done more damage to young African Americans than racism in recent years,” opined Geraldo Rivera—Lamar responded, “Hip-hop is not the problem. Our reality is the problem. … This is our music. This is us expressing ourselves.” Could “Alright” be, as one Twitter user suggested, “the new Black national anthem?”

It’s a complicated question. The widely recognized black American national anthem is actually “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” not “We Shall Overcome.” Both songs are associated with the protests of the civil rights movement and bear some thematic similarity to “Alright.” In “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” for example, the lyrics, written as a poem by school principal James Weldon Johnson and first publicly performed in 1900 in honor of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, are proud and uplifting:

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

“We Shall Overcome,” which in its early incarnation had slightly different lyrics (and the title “I’ll Be All Right”), is likewise optimistic:

The Lord will see us through, The Lord will see us through,

The Lord will see us through someday;

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe,

We shall overcome someday.

It’s worth looking at the context in which those Black Lives Matter protesters were chanting “Alright.” The activists had convened for a conference in Cleveland when an allegedly drunk 14-year-old boy was arrested outside the venue and allegedly roughed up by police. Demonstrators gathered around the scene, locked arms, and were pepper sprayed by police. What the viral clip of the Cleveland protesters doesn’t make clear is that, according to ABC 5 Cleveland, the chanting of “Alright” came after the boy was treated by emergency medical technicians and then released to family members, instead of being taken to the police precinct—what some at the scene considered a small victory. The song, for those protesters, seems both a way to be defiant and proud in the face of those who don’t see you as anything more than a “race-baiter” or a “thug”—and a way to mark the moments when protest seems to make a difference.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Simon Laessoee/Scanpix via Reuters.

Whether “Alright” can truly become the next “Lift Every Voice and Sing” or “We Shall Overcome” depends, that is, not just on whether it continues to appear at protests but on whether those protests can help yield real progress for the movement—giving even greater weight to the song’s promise that we’ll push on through. For now it’s clear that “Alright” is the absolute perfect song for this moment, in the way that Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam,” James Brown’s “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud,” and Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” all captured their eras. It’s blunt and fed up: “We hate po’ po’/ Wanna kill us dead in the streets fo’ sho’.” Like the rest of To Pimp a Butterfly, it is completely, unapologetically black, with all the complexity that implies. It’s unafraid to bring up the vices of its author (namely, materialism)—“Painkillers only put me in the twilight/ Where pretty pussy and Benjamin is the highlight”—but stresses that those only make him human. (Think of the specious arguments people make to suggest that black people dead at the hands of police somehow “had it coming” because they smoked weed or sold loose cigarettes or just weren’t deferential enough at a traffic stop.) And the song holds out hope that things will get better—because how else do you carry on?