Several passages in this article are adapted from Koji Kondo’s Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack, out now from Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros.—a game that broke sales records and set new standards of game design. Celebrated for its colorful levels, phantasmagoric characters, and intuitive controls, Shigeru Miyamoto’s masterpiece is familiar even to those who’ve never played it. Yet when brought up in conversation, the game rarely incites a discussion of the Minus World, Goombas, or programmable physics. It provokes instead an almost primal urge to belt the music with which Mario’s adventure begins: Ba-dum-pum-ba-dum-pum—PUM!

But those 8-bit bleeps that fill the Mushroom Kingdom so memorably are more complicated than they sound. Unlike most game music of the time, the original Mario score was not put together by a computer programmer with little musical background; it was meticulously crafted by a talented composer—the first to be hired by any game company—who elevated music to an unprecedented role in video game design. His name: Koji Kondo.

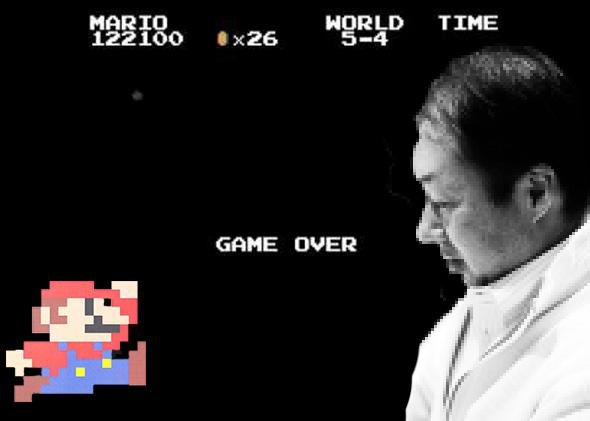

It’s easy to take Kondo’s work for granted, downplaying his talent as a mere knack for writing memorable tunes. But the truth is quite different. Kondo managed to create rich musical tapestries with severely limited means. The Nintendo Entertainment System’s programmable sound generator—Kondo’s orchestra—had just three monophonic sound channels, a noise channel, and a rarely used sample channel. To a composer, that’s the equivalent of two alto flutes, a bass clarinet, and a snowy television screen. And that’s to say nothing of the severe memory constraints that required Kondo to keep his tunes short and repetitive. Try doing that without driving a gamer nuts. Not so easy! Yet Kondo crafted something that still resonates with the masses 30 years after its conception. Even the four-second “Game Over” theme—our window into his craft—oozes compositional rigor, technical knowhow, and inventive spirit.

Transcription courtesy Andrew Schartmann

Kondo’s artistry, however, is only part of the story. Nintendo’s dedication to quality game design, fueled by a strong desire to avoid mistakes that caused other companies to perish in the video game crash of 1983, opened the door to forward-thinking minds. Any composer at Nintendo in the 1980s would’ve benefited from the company’s synergy, especially with now-legendary game designer Miyamoto (Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda) at the helm. But Kondo went the extra mile. Rather than compose run-of-the-mill tracks, he used Nintendo’s collaborative environment to develop core aspects of a new compositional philosophy—one driven by a perfect marriage of game design, gamer experience, and music: “I wanted to create something that had never been heard before,” he said, “where you’d think, ‘This isn’t like game music at all, [is] it?’ ”

In the spirit of a studio album, Kondo created a unified set of pieces without sacrificing the individual character of each. This move alone is enough to cement his place in video game history. Of course, it didn’t hurt that Super Mario Bros. was originally packaged with the Nintendo Entertainment System, guaranteeing that every kid with the console would have Kondo’s tunes etched into their eardrums. But this should not detract from Kondo’s musical vision—a vision that pervades his work and continues to influence the industry as a whole.

At the 2007 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, Kondo outlined the basic tenets of his approach with three keywords: interactivity, rhythm, and balance. This musical Triforce encompasses Kondo’s lifelong contribution to game music. What makes his music so special is that no passage, no matter how short, is exempt from these compositional criteria—as “Game Over” illustrates, even music that will be heard only once during almost every playthrough of the game is carefully molded with them in mind.

Interactivity

The interactive aspect of this theme is self-evident: When Mario missteps on his final life, the music kicks in to tell us that our adventure is over—at least temporarily. In short, the soundtrack responds to the player’s actions. Less evident, however, is how the music interacts with the player’s psychology. And this is where Kondo sets himself apart.

In 1985, Nintendo escaped the blackness of arcade screens by adorning Mario’s first level with a bright and cheerful blue sky. Ever since, the company has developed its whimsical image through cutesy games that downplay the darker side of life. This is why Kondo insists on saying “Play again!” rather than “You’re done for!” with his music. No matter what level you’re on, any Mario “death” is greeted first by the “Power Down” theme—a brief excerpt from the “Overworld” tune that recalls the playful bounce of Level 1-1. When Mario has no lives left, the “Game Over” ditty that follows begins with the familiar three notes of the “Overworld” theme. When played side by side, these themes sound like the beginning of a new “Overworld” loop—renewal instead of defeat, and certainly not death. And so Kondo combats the psychology of defeat with a subtle reminder of where we began and where we can begin again.

Rhythm

Kondo’s take on rhythm is more complicated. In one respect it refers to the syncing of music with on-screen animation (e.g., when Cheep-Cheeps flap to the beat of the “Underwater Waltz”). But in another respect, it refers to a player’s inner movement as he or she guides Mario through the Mushroom Kingdom. Think of it this way: If you play the game without sound, an internal rhythm emerges based on jumping patterns, running speed, and the like. In Kondo’s view, it’s possible to harness this rhythm and build it into the music. Anything less is filler.

The most visceral example of this is the “Overworld” theme. As Mario jumps from platform to platform—a stunt that causes real anxiety in players—the music mixes percussive triplets with a syncopated duple melody. In other words, it grooves in twos and threes at the same time, with several notes sounding off the beat. The result sounds off-kilter, just like the gamer who can’t quite find her footing.

Another of Kondo’s strategies is to interrupt the established rhythm—the steady beat to which we entrain. This is precisely what happens in the “Game Over” theme. By incorporating a ritardando (i.e., a gradual slowing down) into the music, Kondo forces us out of our rhythmic groove. With no steady pulse, our internal dance comes to an end. The idea is to make the “Game Over” message as visceral as possible: We don’t just see words on a screen, we feel their meaning in our bones.

Balance

According to Kondo, balance in video game music exists on multiple levels. At a local level, music and sound effects must harmonize, such that neither overpowers the other. And at a global level, the soundtrack must cohere as a single unified gesture. Although this sounds esoteric, it’s rooted in compositional choices that can be studied and explained. Ultimately, Kondo’s balance refers to the set of musical features responsible for that distinct “Mario sound.”

Kondo achieves balance with the “Game Over” theme by reusing music from the “Overworld.” As I’ve noted, the syncopated notes in the first measure recall the bounce and excitement with which Mario’s journey began. But something’s not quite the same—this time Kondo silences the noise channel, which had previously provided a lively percussion track in the corresponding part of the “Overworld” theme.

Transcription courtesy Andrew Schartmann

Kondo then takes us off course by lengthening the last note of the measure (it’s no longer staccato) and placing those that follow firmly on the beat. This neutralizes the music’s sprightly character and takes the familiar tune in a new direction—one that is appropriately somber. The end result is unity in variety—or, to use Kondo’s word, balance.

* * *

Had Nintendo fostered a less collaborative environment, the Super Mario Bros. soundtrack might have been nothing more than background noise. But the company’s gamble—hiring a young composer, giving him rudimentary tools, and freeing him to make new, adventurous music—paid off. Now a new generation of composers is making more complex and sophisticated music for video games—but it’s using many of the same techniques that Kondo pioneered 30 years ago.

Several passages in this article are adapted from Koji Kondo’s Super Mario Bros. Soundtrack, out now from Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series.