The gleaming white skin and hairless head. The emaciated body carried out on a stretcher. The worshipful natives on every side, fulfilling even the most capricious commands. The almost spectral character of Kurtz, from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, seems like one of the author’s most improbable figures. We never so much as learn his first name. But was he based on a real person?

Many scholars think so. Over the decades, research has led to viable prototypes in several members of King Leopold’s colonial government in the Congo—the setting for the 1899 novel—and other individuals Conrad might have encountered while traveling through that region.

Three years ago, I stumbled across a potential flesh-and-bone Kurtz of my own, in an unlikely place, and without consciously looking. I was just beginning to draft my new novel, The Last Bookaneer, about rival literary pirates infiltrating Robert Louis Stevenson’s life in the Samoan Islands in 1891. To prepare my approach to Stevenson’s character, I reread Heart of Darkness in search of parallels between the ways in which Conrad’s immortal character, Kurtz, “goes native” and Stevenson’s striking experience as a European in tropical exile.

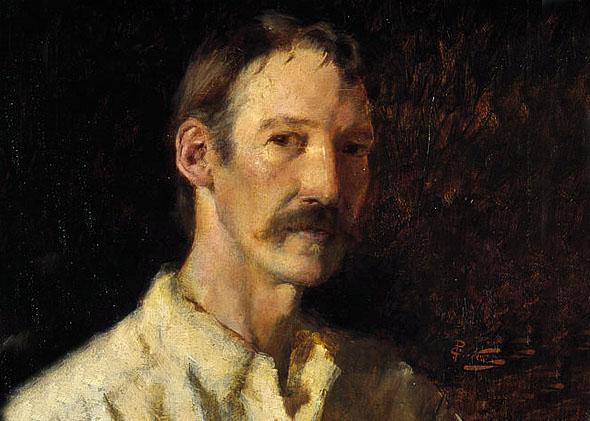

In one dramatic photograph from 1892, shirtless Samoan natives with axes and palm-leaf kilts surround an emaciated, wild-eyed middle-age white man in light-colored flannel. This is Stevenson. The author of Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde had relocated his family two years before to Upolu, the island capital of the nation of Samoa, to revive his fragile health and to sate his lifelong wanderlust.

Image via Memories of Vailima/Isobel Field/Creative Commons

The expatriate writer adopted Samoan titles for their new estate (“Vailima,” meaning five streams) and for himself (“Tusitala,” meaning the teller of tales). The family hired a large and loyal staff and depended upon them for physical protection in the event that discontented natives ever turned against the white colonists. The servants, in turn, relied on the Stevensons for safe harbor from the whims of the foreign consulates, particularly the dominant Germans.

Around the time the Stevenson family settled in Samoa, Joseph Conrad was crisscrossing the Pacific as a sailor. The two writers would never meet. But in March 1893, a pair of young adventurers returning to England boarded the clipper Torrens at Adelaide, Australia, and met 35-year-old first mate Joseph Conrad (then still going by Jozef Korzeniowski). “For fifty-six days I sailed in his company,” recalled one of the travelers, novelist-to-be John Galsworthy, of the future literary giant. Spending the evenings in conversation, they heard Conrad’s “tales of ships and storms … and the Congo.” Galsworthy’s traveling companion, Ted Sanderson, later recounted that before sailing on the Torrens, he and Galsworthy had planned another stopover in their journey: “We arranged a tour to Australia, New Zealand, and the South Seas, especially Samoa, where we both hoped to meet R. L. Stevenson, for whose writings we both had a profound admiration.”

But the literary pilgrimage hit a snag. Samoa was not a common destination for business or pleasure in the 1890s. “Things did not work out according to plan,” remembered Sanderson, “as we could get no boat from Sydney to Samoa.” So the young men ended up on Conrad’s modest cargo ship, where the three formed lasting friendships.

In all these talks late into the night, it would be reasonable to assume Galsworthy and Sanderson spoke about their thwarted plan to meet Stevenson in Samoa. It’s impossible to know precisely what the would-be pilgrims had heard about Stevenson’s life on the island, but plenty of information was in the ether. Only a few months after the family first settled in Upolu, the Athenaeum, a prestigious literary magazine in London, ran a letter from Stevenson that included a pronouncement that he would stay in Samoa “for good.” This may have been the first public confirmation from Stevenson’s own pen that he was not just taking an extended sabbatical. The Scottish novelist’s relocation became a subject of public fascination.

Critic Edmund Gosse informed Stevenson that “the gossip-columns of the newspapers pullulate with gossip about you that cannot be true” and included amusing mock examples about Stevenson becoming the king of Tahiti and eating his meals with a silver pin. Gosse’s letter continues: “Since Byron was in Greece, nothing has appealed to the ordinary literary man as so picturesque as that you should be in the South Seas.”

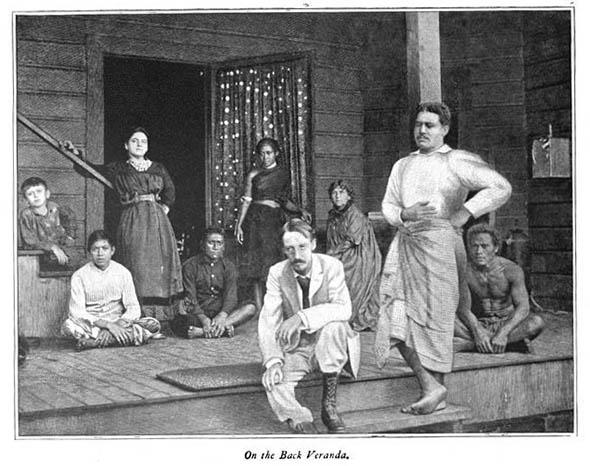

Image via Memories of Vailima/Isobel Field/Creative Commons

The potential contents of the late-night bull sessions on the Torrens could shed light on some intriguing resemblances between the future fictional colonial despot, Kurtz, and the larger-than-life Samoan incarnation of Stevenson. The most obvious parallel is that of a European with a magnetic personality making a kind of a fiefdom for himself among the natives. Stevenson labeled himself not just “head of a plantation” but “Chief Justice of Vailima.” Even if somewhat tongue-in-cheek, the title reflects reality. Stevenson became a kind of independent authority on Upolu, with chiefs “from far and near” (as one English visitor observed) visiting to ask for the novelist’s advice and influence. Recall Marlow’s description of Kurtz’s relationship with the native peoples: “He was not afraid of the natives; they would not stir till Mr. Kurtz gave the word. His ascendancy was extraordinary. The camps of these people surrounded the place, and the chiefs came every day to see him.”

With the grotesque violence surrounding Kurtz in Conrad’s novel—including a collection of decapitated heads (Stevenson reported those signs of war around Upolu, too)—it’s easy to forget that Kurtz is also an author. He’s writing a report on the situation in the Congo for an organization called the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs. Kurtz’s prose turns out to be quite effective, at least according to Marlow, who after reading the report in manuscript notes the “unbounded power of eloquence—of words—of burning noble words.” Stevenson had been working on his own report on the situation in Samoa, which became A Footnote to History, his 1892 account of the Samoan political turmoil triggered by foreign intervention. In the first sentence of his preface, Stevenson calls it a “pamphlet.” Kurtz uses the same word to refer to his report, pleading repeatedly that Marlow take care of “my pamphlet.”

Both real and fictional authors have unrealistically high hopes for their pamphlets. “Immensely proud” of his report, Kurtz tells Marlow “it was sure to have in the future a good influence on his career,” though it never did. Stevenson believed his tract could actually sway the foreign governments toward his vision for Samoa, which involved restoring an exiled native as king.

In a letter to English critic and scholar Sidney Colvin, Stevenson wrote of Footnote “pray God that it be in time to help,” and the subtext is clear—not just in time before the next civil war inevitably overtook the islands, but while Stevenson’s health allowed him to write. Both Stevenson and Kurtz write their respective pamphlets on what seem to be their deathbeds (Stevenson died at Vailima about two years after publication and was buried on a volcanic mountain).

As early as 1950, Stevenson biographers took notice of Galsworthy and Sanderson’s attempted sojourn to Samoa and their subsequent voyage with Conrad. Meanwhile, scholars have long studied Stevenson’s literary influence on Conrad, in part because both wrote seafaring stories and a torch seemed passed. We know that Conrad was an admirer of Stevenson’s work, and in fact that he thought more highly of Stevenson’s South Seas nonfiction writings than of his novels, at least according to Colvin, who knew both men. To my knowledge, however, no one has connected the next set of dots, not just from Stevenson’s writing to Conrad’s, but from Stevenson’s Samoan persona to Kurtz. Why not consider whether Stevenson’s grandiose island life influenced Conrad’s masterpiece? Since the middle of the 20th century, the academy has conditioned us to stay grounded within texts and steer clear of writers’ biographies for insights while biographers are often timid about the kind of playful speculation that we can undertake here in Slate. Readers, myself included, tend to wonder about the sources for characters the likes of Kurtz, Sherlock Holmes, and Jay Gatsby—larger-than-life, mysterious, existing on a kind of separate plane—and in doing so we are continuing the quests of the narrators who tried first (Marlow, Watson, and Carraway).

If Conrad absorbed some of Stevenson’s attributes into Kurtz, it would be just one literary development to come out of the passage of the Torrens. “Tall, handsome, bearded” Ted Sanderson, wrote biographer Jeffrey Meyers, served as a “prototype” for the titular character in Conrad’s Lord Jim. Galsworthy—who became a Nobel Prize–winning writer for his fiction—used Conrad as a model for the character of Armand in his story “The Doldrums.” No surprise that another man from that passage—not in the flesh but on the tips of their tongues—might have gotten mixed up in the brew of life and fiction.

None of this is meant to suggest that Robert Louis Stevenson equals Kurtz, any more so than Marlow, with his “propensity to spin yarns” about the Congo aboard the Nellie equals the novelist Conrad aboard the Torrens. The megalomaniac Kurtz diverges from Stevenson in plenty of ways, and Conrad had other sources from which to draw, including the people he met and heard about during his journeys and, of course, his imagination. But if some of the figures he encountered in the Congo may have plausibly contributed examples of cruelty and specific experiences as traders, other dimensions—the lofty writerly goals and the inescapable charisma—might well have been moved along by word of the exiled Stevenson. Rarely is there a single model for a complex literary character, and writers often aren’t even fully aware of their inspirations. What Marlow notes of Kurtz’s background might have been true of Conrad’s literary creation: “All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz.” Maybe there was some Samoa in there, too.