All celebrity memoirs come loaded with double barrels of doubt—“Did he even write it?” and “Is this actually necessary?” In the case of one Mr. Bruce Springsteen of Freehold Borough, New Jersey, and the book inevitably titled Born to Run, authorship seems guaranteed: The Boss, as his (disliked) nickname implies and his book repeatedly avers, is a control freak. He wasn’t going to let anyone ghost his life story except for his own personal ghosts.

If that doesn’t convince you, here’s the style of the prose:

“Like a Rolling Stone” gave me the faith that a true, unaltered, uncompromised vision could be broadcast to millions, changing minds, enlivening spirits, bringing red blood to the anemic American pop landscape, and delivering a warning, a challenge that could become an essential part of the American conversation. … “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Louie Louie” let me know that someone, somewhere, was speaking in tongues and that absurd ecstasy had been snuck into the Constitution’s First Amendment and was an American birthright. I heard it on the radio.

Crack goes the snare, whirl goes the organ, cue the sax solo.

And then there are the paragraphs in which our memoirist stretches out … his sentences … with ellipses … for tension … and then CLIMAXES WITH PHRASES IN ALL CAPS! (The crowd roars.) If this book wasn’t actually hand-scribbled by the man himself over the course of seven years, as he claims, someone has been working way too hard on an impersonation. There are vivid landscapes, dream sequences, character sketches, personal missteps, sermons on survival and politics and rock ’n’ roll, travelogues, travelogues, travelogues, and rare flashes of sex. In other words, a Bruce Springsteen album, though in a very extended, 503-page, 79-chapter mix.

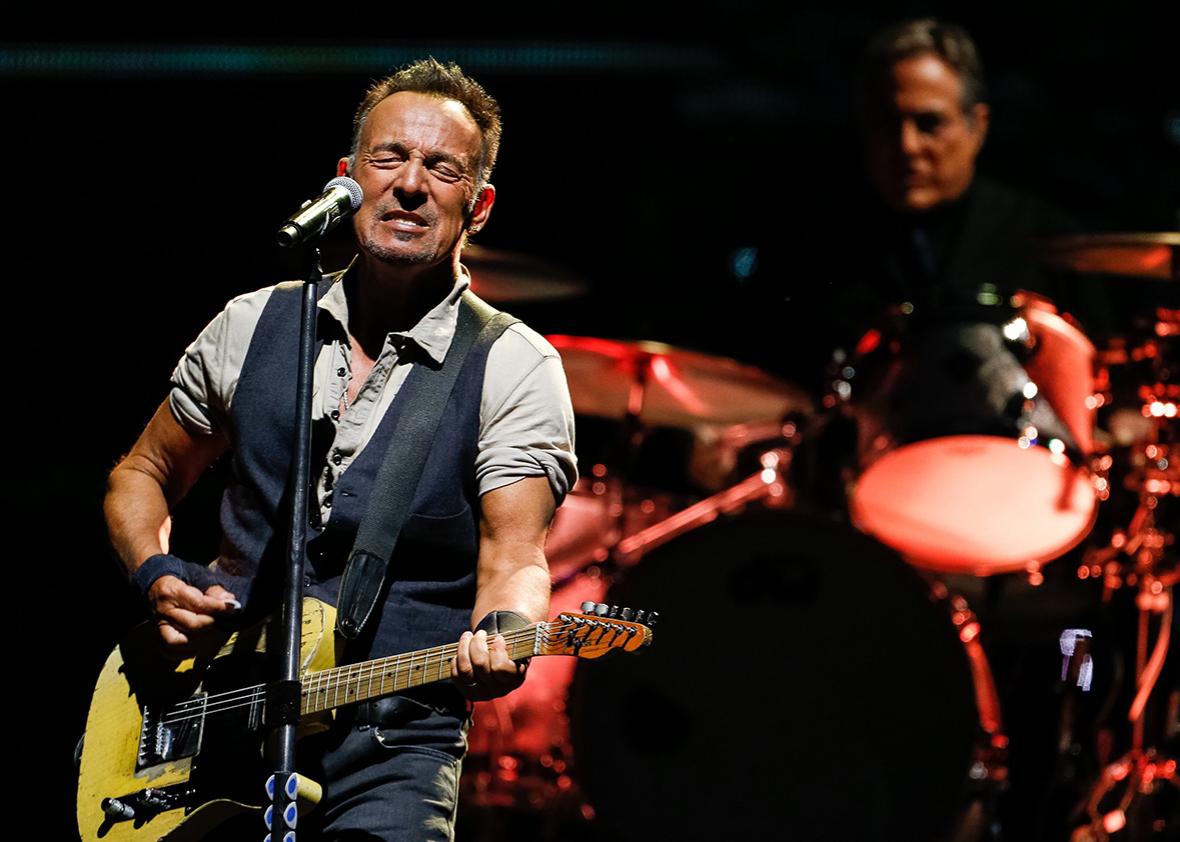

Which leaves the second question: Who really needs it? There’s an oppressive side to the whole notion of a memoir by Springsteen, who turned 67 on Friday. Call it the Bruuuuuuuce! factor. Today the guy is a relic, a very sturdy but perhaps overvenerated one, among the last of the old gods in a religion to which fewer and fewer people subscribe: the faith of the rock era, in which the holy commandments were what muscled but sensitive white dudes in stadiums yelled about America and Chevy engines in 4/4 time. This is not the way most young people now get their kicks, or their transcendence, not as Beyoncé turns domestic crisis water into cultural crisis wine (to mix another liquid metaphor with her Lemonade), or as trans punk Laura Jane Grace defies gender-binary bullies in the band Against Me (whose new album comes out this week).

Springsteen always has been an ink magnet, ever since he was on the covers of Time and Newsweek simultaneously in 1975, when few readers had yet heard any of his songs. There are shelves of worshipful books by fans, critics, and scholars; feature documentaries accompanying the reissues of his most classic albums; and that’s not to mention the multiple fictionalized versions of his life in song after song after song. His book stops in at most of the mandatory stations of the baby boom rock memoir: the rough childhood redeemed by the annunciation of the savior Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show, the Kennedy assassination, second salvation via the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, etc. (Thankfully he doesn’t always dole them out in the expected places.) Yes, Baby Springsteen wisely chose the greatest moment in the history of moments to be born a guitar man. Late in the narrative he writes, “The birthing conditions of today’s musicians will be different — just as valid, but different,” which is a good diplomatic try, but no way does he believe that.

So it’s tempting to tell Springsteen that old rock dudes have had their say and it’s time to pipe down. But there is more to it. This particular relic was always one of the most relentlessly self-examining of those lumbering gods, and he spends as much time tarnishing his silver here as varnishing it. Even at his more florid, he must be conceded a magic with words: He can spin not only a yarn but often an extended analysis, too. Most celebrity memoirs fall apart in the second half, when the compelling origin and rise narrative is followed by the dull triumph and lists of charity works and award shows. Springsteen’s compressed chapters, instead, are assigned fairly specific themes, a level of focus that ensures he continues to have not just anecdotes but things to say. There are slumps, like the chapter in which he tells us about his horses (who knows, maybe that’ll be your jam). Mostly, though, he’s in pursuit of a different kind of throughline, or rather two.

One is of course the story of his career and his bands, up through school dances to the bars of the Eastern Seaboard to European football stadiums: the albums they made and the shows they played. It has colorful settings and characters, strategizing and setbacks, and conflicts and lawsuits and reconciliations. Its larger meaning, if it has one, is as an exhausting itinerary of labor. If you ever feel guilty about your own productivity, Springsteen’s book will not be comforting. The intimidating feeling kicks in before our protagonist has even graduated from high school, by which point he’s already put together multiple bands, one of which (the Castiles) released a single, became “the big dogs” on the local circuit, and moved up to playing Greenwich Village clubs. It continues on into the last demonically animated four-hour (or more!) stadium concert with the once-fired and now-reunited E Street Band, as he skids on both knees toward septuagenarian status. Stardom always comes out of ambition as much as talent, sure, but in Springsteen’s case it’s as if the talent itself was willed into being out of sheer want, need, and stubbornness. He admits the role luck’s played, but few rock picaresques seem less accidental.

Thus, the more compelling thread in the book, the one that justifies its existence, is about where that drive, dare we say mania, came from. Even casual fans may already know about his Italian-Irish Jersey family’s humble circumstances (which were starker than I knew), as well as his father’s drinking, moodiness, and opposition to his son’s ambitions. “I haven’t been completely fair to my father in my songs,” Springsteen writes, “treating him as an archetype of the neglecting, domineering parent … a way of ‘universalizing’ my childhood experience. Our story is much more complicated.” Specifically, it’s a story about the hereditary mental illness (diagnosed at one point as paranoid schizophrenia, but maybe just bipolar disorder) that ate away at Doug Springsteen and burdened his wife all their lives. Some of the best chapters about it come late in the book, when Bruce is a family man himself but still dealing with his now-elderly father’s erratic and dangerous behavior and searching for some peace and reconciliation between them. (It comes, in small but touching ways.)

The added revelation is that Springsteen has had to cope with his father’s legacy not just psychologically but genetically: He undergoes his own major depressive swings, in fact several of them in recent years. The idea of the Boss on antidepressants, or spending months unable to stop crying, is a touch startling, although it shouldn’t be for those who’ve heard, say, Nebraska. Touring is his way of self-medicating, but he tends to crash when he is off the road, sometimes severely, because “when you’re on tour, you’re king, and when you’re home, you’re not.” In fact, he credits years of work with his psychiatrist for having made this book possible. He is often vague about his specific symptoms, but passive aggression and surly withdrawal are definitely two. His relationships with women were the major casualties, until his lasting second marriage, to Patti Scialfa, the Jersey girl and E Street Band backup singer who proved to be the one who could both endure and challenge his caprices.

Had Springsteen focused in on this family saga and downplayed the professional one, Born to Run would be a slimmer and more perfect book, a more powerful literary and emotional one. However, there are plenty of sad family memoirs out there; the amalgam of personal and vocational tale makes the book messier but also somewhat distinctive, the firsthand account of a man who is at once running like hell from his demons and also collaborating with them in a highly disciplined, satisfying working partnership.

His disclosures here are rich, deep, and useful to help destigmatize mental illness. Still, I finished the book knowing I wouldn’t want to be Bruce Springsteen’s spouse, and not so sure about friend or bandmate, either. It’s a credit to the openness of his writing that this love-hungry celebrity chances making people like him a little less. Yet in places he also sidesteps slightly harder admissions, the ones not just about his pain but about his pleasures: the selfishness that makes someone chase the limelight, which seems to have been part of his makeup from the start.

Early on he blames his grandmother, who often had his charge, for her doting indulgences, letting him stay up all night as a small child. When this mixes badly with schoolwork, young Springsteen takes his stand, refusing to acknowledge “a world where I am not recognized, by my grandmother’s lights and mine, for whom I am a lost boy king. … I don’t know shit, nor care, about ‘the way things are.’ I hail from the exotic land of … THINGS THE WAY I LIKE ‘EM.” Sure sounds like a Boss in waiting.

A reader might think about that passage later, for example, when he talks about deliberately setting up conflict between his manager and sometime producer Jon Landau (his foil for discussing “the life of the mind”) and his best friend and lead guitarist Steve Van Zandt (all instinct, opinion and energy). It’s for the good of the music, the good of the band, Springsteen writes, but he admits it can be at the expense of the two men’s feelings. He can seem rather callous about how he instrumentalizes relationships, pun intended.

The most vexing case is that of the late saxophonist Clarence Clemons, the only long-term black member of the E Street Band, “the Big Man,” as Springsteen always called him. Theirs is possibly the most iconic cross-racial partnership in rock history—think of the Born to Run album cover, the two musicians leaning against each other as they often did onstage. Yet the nature of the partnership is discomfitingly blurry in his telling. He and Clemons seldom spent personal time together outside the band, and while for Springsteen work decidedly is a form of love, their vaunted closeness comes to seem only partial. He treasured Clemons musically, but it seems just as vital to him that there is a black man in the band, period, as a genuflection both to rock history—“There he was,” Springsteen writes of their first meeting, “King Curtis, Junior Walker and all my rock ’n’ roll fantasies rolled into one”—and to liberal ideals of integration and social change.

As my fellow Slate critic Jack Hamilton discusses in his new book, Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, the 1960s in which Springsteen came of age was the period when rock ’n’ roll was whitewashed into rock: Instead of a music through which America worked out its racial tensions, it became the music, we might say, through which young white Americans dealt with the fact that their fathers were abusing them. By extended metaphor, it also became sometimes the music through which young white Americans dealt with the fact that their country was abusing other parts of the world. But what then about its own racial legacy? Clemons was Springsteen’s way of answering that question, but Clarence the person ends up seeming second to Clarence the symbol, which does not sit right.

Springsteen writes sensitively about race issues several times here, including with regard to his relationship with Clemons. I’m not accusing him of anything except some inevitable Jersey-boy generational blinders, but it is a reminder of why we might not want to look back too nostalgically on rock’s supposed glory days.

He is better, overall, on another aspect that’s troubled many people about the Springsteen hero complex, its fixation on masculinity. He frets over it in these pages, about the unhealthy parts of the ideals of manhood he inherited and the misogyny that complements them, both in his own psyche and in the rock lifestyle. It was not easy for the men to adjust when Scialfa “broke the boys’ club,” Springsteen admits, with both grudge and gratitude. “The E Street Band carried its own muted misogyny (including my own), a very prevalent quality amongst rock groups of our generation.”

He acknowledges that the insecurity that made him push himself to extremes was always partly a desire to become the manly figure he felt his father despised him for not fulfilling. Think of that gym-pumped 1980s Born in the USA look—which he jokes ultimately read as a gay leather-bar daddy look—but beyond that, too, his characteristic working-class framing of his art, always as a “job” that he was doing in service to the demands and needs of the audience: “I’m a repairman,” he writes, fixing the broken hearts of the masses. “So I, who’d never done a week’s worth of manual labor in my life (hail, hail rock ’n’ roll!), put on a factory worker’s clothes, my father’s clothes, and went to work.”

It is this uncanny and compulsive ethic of service, carried through in his music’s conscience and his willingness to leave every drop of blood and sweat on the stage floor, that still commands my respect for Springsteen, against and beyond the band-of-righteous-bros entitled image. In many ways, as inequalities widen, it becomes more countercultural than ever. There’s a moment in the book when he goes to see Against Me (before Laura Jane Grace’s coming out) because his son and friends are big fans, and they learn the bassist has not only Springsteen’s image tattooed on one arm but a whole verse of “Badlands” (from his leanest, punkest, and I would contend best album, Darkness on the Edge of Town) adorning the other. For all that Bruuuuce is a holdover from an age gone by, I suspect Springsteen himself might be a resource to which seekers yet to come will keep returning. To the extent this book deepens that well, it’s worth every overwrought and self-serious syllable.

—

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen. Simon and Schuster.

See all the pieces in the Slate Book Review.