A new Beowulf translation has come flowing out of the fiend-infested mist: The author is J.R.R. Tolkien, who upon his death in 1973 left behind reams of lecture notes about the poem, as well as a typescript. According to his son Christopher, the typescript, “on very thin paper,” is in poor condition, the “right-hand edges being darkly discoloured and in some cases badly broken or torn away.” In this it bears “an odd resemblance to the Beowulf manuscript itself,” almost consumed in an 18th-century fire, “the edges of the leaves … scorched and subsequently crumbled.”

The sense of precariousness and melancholy in that shared detail is reflected in the poem as a whole. (Tolkien, with his love of scholarly trivia, would have loved the coincidence of two texts dissolving at the margins.) Beowulf begins when a mysterious foundling arrives at Denmark from shores unknown and ends with a gray-haired king on a pyre, his spirit passing into the beyond. The bright tale in between is transient—already disintegrating at the edges long before it was even written down—and past those borders stalk the monsters, incomprehensible, laden with our oldest fears.

Tolkien was 34 when he finished the translation, one year into his post as a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. Ahead of him lay decades of Old English scholarship and study, as well as The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy, for which he’s best known. “I have all Beowulf translated, but in much hardly to my liking,” he wrote to a friend in 1926. He would later go back and emend the manuscript as his thoughts on the poem evolved; the edition coming out this month splices the heroic narrative with extras and deleted scenes—notes, commentary, a poetic condensation of his prose translation (the Lay of Beowulf), and a colloquial retelling, the Sellic Spell, that reads a lot like fan fiction.

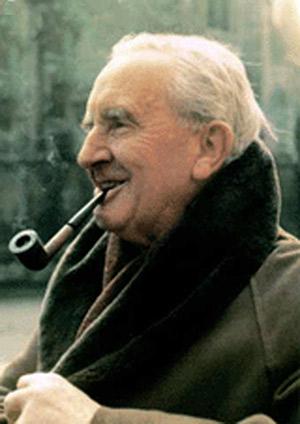

Photo by John Wyatt

Tolkien’s aim, according to his son’s introduction, was to hew “as close as he could to the exact meaning in detail of the Old English poem, far closer than could ever be attained by translation into ‘alliterative verse.’ ” So this Beowulf runs unmetered, in sentences, without the characteristic Anglo-Saxon thumping beats. Tolkien once wrote that Old English poetry was “more masonry than music,” and his prose translation largely reflects that architectural bias. Stacked clauses and other syntactical pileups impede the tune, though you can sometimes hear a latent rhythm: “Eagerly the warriors mounted the prow, and the streaming seas swirled upon the sand.”

Luckily, the plot and mood elements of Beowulf survive the form-switch. This is still the story of a Geatish warrior who crosses the sea to succor the people of Denmark and their once-glorious king. For 12 years a monster called Grendel has haunted Hrothgar’s meadhall, gobbling up his men, upsetting its order of wealth and song. Beowulf defeats Grendel by tearing off his arm, and then dives into a demonic mere to finish off his mother. He returns in victory to Geatland, weighed down with Hrothgar’s gifts of treasure, and rules for 50 years—“aged guardian of his rightful land.” And then a dragon wakes in a deep, gold-glittering barrow and begins to fill the sky with fire. Beowulf must kill the worm in a final act of bravery, which he carries out at the cost of his own life. Menaced by political enemies, kingless, his people conduct his funeral and wait for the end.

Womp. Of course, Beowulf is more than that suddenly collapsed lung of narrative. It’s a rising and a setting, remote, strange, and sad, and it contains some of literature’s brightest illuminations and deepest, least knowable darks. In his 1936 essay, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” Tolkien made an argument for the poem not just as a historical or cultural document but as a work of art. His theory—that behind the text hovers a unified and masterfully potent creative imagination—transformed the way the world read Beowulf. People began to see the loveliness in it (the lamplight, the hearth heat, the bonds of kinship) offset by the elegy (“resting places swept by the wind robbed of laughter.”) Novels could explore its philosophical root system. Seamus Heaney could write in the 2000 introduction to his own translation: “This is not just metrical narrative full of anthropological interest and typical heroic-age motifs; it is poetry of a high order, in which passages of great lyric intensity … rise like emanations from some fissure in the bedrock of the human capacity to endure.”

Shoot. Oh shoot. I shouldn’t have mentioned Heaney. I’m sorry. Now I feel like I need to compare the two Beowulfs, and though I can’t speak to their relative scholarship, in terms of pure, thane-devouring pleasure, there’s no real contest. “It is a composition not a tune,” wrote Tolkien of the Anglo-Saxon original. Yet the Irish bard Heaney made it both. His Beowulf, at once airier and rougher, feels more contemporary, less bogged down in academic minutiae. Grendel equals “reaver from hell,” “dark death-shadow who lurked and swooped in the long nights on the misty moors.” By contrast, here is Tolkien: “Grendel was that grim creature called, the ill-famed haunter of the marches of the land, who kept the moors, the fastness of the fens, and unhappy one, inhabited long while the troll-kind’s home.”

I understand how some might prefer Tolkien’s version. The description, stately and involved, seems sprinkled with an Arthurian grandeur; readers who love the Lord of the Rings may resonate to that high diction and steady, exact pacing. And it’s not that Tolkien can’t do immediacy. When he first conjured the dragon—“Now it came blazing, gliding in looped curves, hastening to its fate”—I was breathless (and very reminded of Smaug). But he just as often loses the story’s thread in a kind of reverent hairsplitting. After that incandescent dragon sentence, we get: “The shield well protected the life and limbs of the king renowned a lesser while than his desire had asked, if he were permitted to possess victory in battle, as that time, on that first occasion of his life, for him fate decreed it not.” I think that means that Beowulf’s arms buckled in the flames, but the translator’s admirable fidelity to—and, likely, his matchless handle on—the precise turnings of the Old English fogged up the action.

But maybe you waive your right to those sorts of complaints when you open a Tolkien rendering of Beowulf. (And it’s important to remember that Tolkien never intended this manuscript for publication.) The fantasy-shaper of Middle Earth was also a “don’s don,” a leading scholar more or less fluent in Greek, Latin, Old English, Welsh, Finnish, and a handful of Germanic Gothic tongues, who modernized medieval lyrics like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. Where Heaney has his ear to the ground, trained on a nightmare’s thudding footsteps, Tolkien’s nose is in his books.

Tolkien’s assessment of the Beowulf poet is revealing: “It is a poem by a learned man writing of old times, who looking back on the heroism and sorrow feels in them something permanent and something symbolical.” Tolkien himself was a “learned man” who, gazing on ancient things, felt acutely, even as he brought worlds of erudition to bear on his responses. Probably, the project of scholarship refined and deepened those responses. Nostalgia and regret, so central to Beowulf, are presumably familiar mental states for someone who spends much of his time sifting through the past.

So the new translation seems especially attuned to transience and loss, from Beowulf’s premonitions before he fights the dragon (“heavy was his mood, restless hastening toward death”) to a gorgeous passage about the last survivor of an ancient civilization burying his gold. In his commentary on the scene, Tolkien remarks, with great emotional sensitivity:

The whole thing is sombre, tragic, sinister, curiously real. The “treasure” is not just some lucky wealth that will enable the finder to have a good time, or marry the princess. It is laden with history, leading back into the dark heathen ages beyond the memory of song, but not beyond the reach of imagination.

Actually, the commentary may be the best part of this new Beowulf. Not only does it offer context and aid (teasing apart the webs of loyalty and conflict entwining Geats, Danes, and Swedes, for instance), but Tolkien-as-guide is delightful, an irresistibly chatty schoolmaster in the Chaucerian mold. Also an ornery one. I got pissed when I read the famous opening lines and saw “the sea where the whale rides” instead of the familiar “whale-road.” So I flipped, pissily, to the back, where Tolkien explains that he derived the phrase from a kenning: one of several “pictorial descriptive compounds” that “can be used in place of the normal plain word.” I know what a kenning is. Where the hell was whale-road?

Funny I should ask. “It is quite incorrect to translate it (as it is all too frequently translated) ‘whale road,’ ” grouses Tolkien. “It is incorrect stylistically since compounds of this sort sound in themselves clumsy or bizarre in modern English … in this particular instance the unfortunate sound-association with ‘railroad’ increases the ineptitude. It is incorrect in fact … ”

The scolding goes on for, I joke not, three pages. At the end, Tolkien pronounces, Q.E.D., that the “word as kenning therefore means dolphin’s riding. … That is not evoked by ‘whale road’—which suggests a sort of semi-submarine steam-engine running along submerged metal rails over the Atlantic.”

Burn! In the same way, Professor Tolkien kvetches about scribes who may have mistakenly written the name “Beowulf” where they meant an earlier folk presence, Beow. (“One of the reddest and highest red herrings that were ever dragged across a literary trail,” he sniffs.) But the glossary contains more than shade. At one point, Tolkien considers Beowulf’s ancestor Scyld Scefing, who sails into the lives of the Danes from a magical “elsewhere.” Scyld’s name means something like Shield Sheaf-guy; he is modeled in part on pagan myths about a harvest god washed ashore in a shining, corn-filled ship. Around J.R.R.’s commentary Christopher Tolkien has woven descriptions of “King Sheave” from a time-travel book, The Lost Road, that his father penned but never published. (The figure turned into a minor obsession for Tolkien, and perhaps a model for Gandalf the Grey.) As you read, these layers and echoes become seductive, sounding the edges of a vanished continent of meaning. It’s as if, through intricate cataloguing, you might retrieve the old things from the past—as if scholarship were chiefly memory, sent out like a flare against the dark. Desperately, Hrothgar’s scop sings “how the Almighty wrought the earth … how triumphant He set the radiance of the sun and moon … and adorned the regions of the world with boughs,” while, outside, “the shapes of mantling shadow [come] gliding over the world.”

What I am trying to say is that Tolkien’s learning and Beowulf’s patterns of gloom and fragile light feel intimately related. The finicky diction (as well as everything in the commentary section) follows from a sensibility that knows too well what happens when order begins to fail. You can see the signs of social disintegration when Tolkien evokes his hero’s pyre: “Then upon the hill warriors began the mightiest of funeral fires to waken. Woodsmoke mounted black above the burning, a roaring flame ringed with weeping, till the swirling wind sank quiet, and the body’s bony house was crumbled in the blazing core.”

In the spirit of collaborative scholarship, or maybe of genealogy, here is Heaney with the next few lines:

with hair bound up, [a Geat woman] unburdened herself

of her worst fears, a wild litany

of nightmare and lament: her nation invaded,

enemies on the rampage, bodies in piles,

slavery and abasement. Heaven swallowed the smoke.

In this moment Beowulf collapses all the nice distinctions scops, poets, and academics try so hard to preserve. The bound hair seems to pour out of its constraint along with the vocal cascade of terror and grief. Images bleed together as the bodies heap. Then, suddenly, the entire vision is consumed, made into “smoke,” and absorbed by an implacable sky.

Meanwhile, if a group of scholars hadn’t broken into a burning building in 1731 to rescue the Beowulf codex, we’d know nothing of Grendel or Hrothgar. I do not begrudge Tolkien his pedantry in the face of the void. “Almost fate decreed,” he writes of the original manuscript, “that shall the blazing wood devour, the fire enfold.” Now his noble translation joins the ranks of the narrowly saved. Hwæt!

—

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary by J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.