On the book table at Urban Outfitters, stacked among the silly Tumblr-to-print tomes that a certain type of young adult tends to store in the bathroom, you will find a curious cultural artifact called Rookie Yearbook Two. A magical thing hiding among sad gimmicks, the book collects a year’s worth of highlights from Tavi Gevinson’s Web magazine for teenage girls. It’s being marketed as a keepsake for regular Rookie readers or as a gift for your niece, so it will be overlooked by most adult eyes. But it shouldn’t be.

As with Gwyneth Paltrow and GOOP, it is difficult to separate Gevinson the person from Rookie the brand. A savvy 17-year-old businesswoman, she is adept in straddling seemingly contradictory worlds. She is a veritable media force and a moony teenager who likes to make flower crowns, and in both roles she is utterly convincing. A smart editor whose work is featured on the toilet-book table, she’s an expert in blurring boundaries.

With Yearbook Two (and its predecessor, Yearbook One), Gevinson has found a novel way to bridge the worlds of Web and print. Writing on the Web is routinely undervalued, in part because it’s ephemeral. We live in a golden age of cultural criticism, but much of it slips through the cracks. Hundreds of thousands of words by original voices like Jacob Clifton and Gabe Delahaye are available exclusively (for free!) on the Web. But with so many outlets publishing at a breakneck pace, the half-life of a successful Web item is maybe 36 hours. If you aren’t actively monitoring the Internet during that brief window, well, too bad—you’ll become aware of a given post only, if at all, by fluke.

This milieu is stressful for everyone. As a reader, it’s impossible to keep up. As a writer, it’s difficult to make yourself heard. And as a Web concern, it’s hard to know what to do with a vast archive of stagnant material that’s getting buried deeper by the day. Sites like the Awl and the Atlantic have turned to subscription-based apps to repackage (and remonetize) their own content. As e-platforms, the only added value these apps really offer is in cutting through a week’s worth of static; each is a service more than an aesthetic entity. In the print format, Rookie’s yearbooks are both.

Published by Drawn and Quarterly—a house otherwise known for printing literary comics by artists like Daniel Clowes and Gilbert Hernandez—Yearbook Two has been playfully designed. It features new illustrations, celebrity doodles, artful collages, tarot cards, and stickers. It is a cool thing to hold in your hands. Most of the writing has been imported from the website, unedited except for length. Some of the material (e.g., essays on college applications and menstruation) will be of interest only to teenagers, or adults who wish to relish the feeling of no longer being teenagers. But there’s also plenty of stuff for the rest of us, like a terrific essay by Jenny Zhang (from the magazine’s “Literally the Best Thing Ever” column) on M.I.A; themed playlists; and frank meditations on identity, sex, and love. There’s the occasional misstep (including a mortifying piece that affirms John Mayer’s opinion that “your body is a wonderland”), but that’s the curse of any anthology.

Gevinson has also included all of her letters from the editor, which she publishes on the website each month. Slices of life more than enduring art, they are a small, but effective, touch that creates a palpable sense of time passing as you follow her notes through the seasons. Since Rookie’s aesthetic traffics so heavily in nostalgia, a yearbook—a sentimental format specifically designed to capture things that are fleeting—is weirdly the ultimate iteration of the Web magazine.

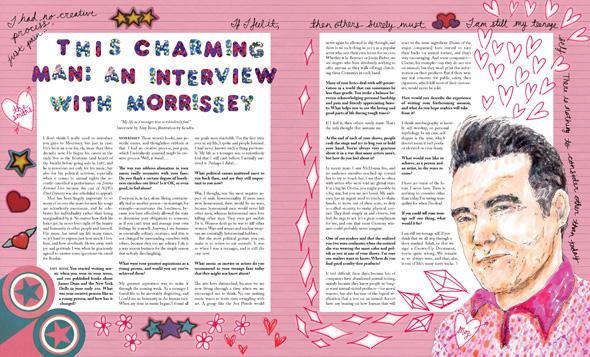

Rookie shines most brightly in its interviews. Consider this excerpt from Amy Rose Spiegel’s conversation with Morrissey, a notoriously difficult subject:

Rookie: The way you address alienation in your music really resonates with your fans. Do you think a certain degree of loneliness enriches our lives? Is it OK, or even good, to feel alone?

Morrissey: Everyone is, in fact, alone. Being contractually tied to another person—in marriage, for example—accentuates the loneliness, because you have effectively allowed the state to determine your obligations to someone, as if you can’t trust and manage your own feelings by yourself. Anyway, I see humans as essentially solitary creatures, and this is not changed by surrounding ourselves with others, because they too are solitary. Life is a very serious business for the simple reason that nobody dies laughing.

Now contrast it with this one from The Guardian:

Guardian: Do you own a valid driving license?

Morrissey: What kind of bland, insipid question is that?

Guardian: It’s a good question, isn’t it? Has anyone asked you it before?

Morrissey: No. But that’s hardly a surprise, is it?

Guardian: I thought it was a beauty.

Morrissey: Why? Because you consider me incapable of operating such large and complex pieces of engineering?

Yearbook Two contains incisive interviews with a wide array of pop heroes, including Carrie Brownstein, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Molly Ringwald, and Chris Ware. At first, it might seem strange that the Rookie universe shares so many cultural touchstones with people twice the age of its target demographic. But, like a long line of teenagers before her—Enid Coleslaw, Rory Gilmore, and teenage me among them—Gevinson’s taste ranges from contemporary fare to artists that “belong” to past generations. Her perspective is youthful, but her sensibility is timeless.

More than taste, what’s of interest is the quality of discourse. Often conducted by teenagers, Rookie’s Q-and-As are consistently among the best in journalism. Why?

“When I interviewed Sofia Coppola for the site, she said she’s consistently drawn to teenage characters when writing films because they have time to be introspective, a luxury that adult lives tend to get too crowded for,” Gevinson writes in the preface, which is one way to answer the question. (While some of the writers at Rookie are grown-ups, you get the sense they all dutifully maintain dream journals.) Another is that Rookie often checks in with celebrities in the off-season, when they’re not necessarily promoting a project. It’s not that Rookie’s editorial approach is contrarian; it’s just not entirely of the world. At the time of this writing, a week after the Breaking Bad finale, it is the only Web magazine I’m aware of that has not published a single word about Walter White. Its coverage is driven by the whims, obsessions, and values of the Rookie staff and, above all, Gevinson.

Courtesy Petra Collins

For now, the literary establishment still promotes a narrow view of what qualifies as “serious writing.” By and large, it is a culture that pigeonholes women writers, undervalues young adult literature, and harbors deep suspicion toward anything on the Internet. Accordingly, Rookie’s treatment in the press, while glowing, is haunted by the air of indulgence with which you might praise a child’s school project. People seem to recognize that Tavi Gevinson is doing great things for girls. The truth is actually much more impressive: She is doing great things. Adults need not turn to Rookie out of nostalgia or to experience catharsis. Read it because it is singular.

—

Rookie Yearbook Two by Tavi Gevinson. Drawn and Quarterly.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.