When Frank Gehry told Spanish reporters earlier this year that “98 percent of everything that is built and designed today is pure shit,” he wasn’t putting his colleagues on blast. Limit “everything” to construction in the West, after all, or even just the buildings that go up in major metropolitan areas like New York City or Chicago, and most of them aren’t designed by architects Gehry would call peers. It’s the retail and residential architecture, the anonymous CVS outlets and invisible apartment buildings, that makes up the dark matter of our built universe, the stuff we hardly detect that surrounds us in every direction.

So after an El Mundo reporter asked him during the same hostile press conference about practicing the “architecture of spectacle,” Gehry gave him the finger. Fair enough: Why focus your hate on stellar architecture, the buildings designed for people to see, when the universe is filled with so much work that’s built not to be noticed?

Of the 2 percent of the built environment that’s not pure shit, there’s still plenty to hate. The following list should be read as a plea for 2015: Leave Frank Gehry alone. Every one of these is worse than Gehry’s Fondation Louis Vuitton, which opened this fall and may in fact be the best building of 2014. It’s time for a new punching bag. The dubious designs and blustering egos collected here all make a strong case for the worst architecture of 2014.

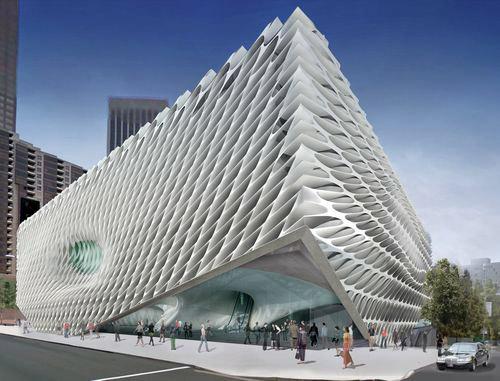

The Broad (Los Angeles, Diller Scofidio + Renfro)

Photo by Joe Wolf/Flickr

Kimball Art Museum (Park City, Utah; BIG Architects)

Progetto Manifattura, Green Innovation Factory (Rovereto, Italy; Kengo Kuma and Associates)

The peekaboo wedge was unavoidable in 2014. Three designs by some of the world’s most prominent architecture firms all seemed to sample the same hook.

True, only one of these designs is sure to see the light of day. The Broad, a contemporary art museum by DS+R, is nearing completion in Los Angeles. Kengo Kuma’s plans to turn a former tobacco factory in Rovereto, Italy, into a mixed-use landmark wedge were revealed this year, but won’t be finished until 2018 at the earliest. And the wedge for Park City, Utah, isn’t going to happen at all. Officials in the ski resort town recently rejected BIG’s wedge, the firm’s second draft for the museum, as not in keeping with Main Street values.

What Park City leaders don’t realize is that the wedge is actually too conventional. Essentially, it’s a jewel-box museum design with fancy façade trimmings. While it’s hard to say where trends like these start, it could have something to do with the very narrow career path that young architects take to get to boutique firms like DS+R, BIG, and Kengo Kuma. How bold can the thinking be that follows the beaten path from Columbia or the Harvard Graduate School of Design through an internship in Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture? That’s not the track that most architects follow, but it is the path to luxe design. Elizabeth Diller (of DS+R) and Kengo Kuma both studied at Columbia; Bjarke Ingels (of BIG) worked for OMA.

All 1,715 Designs in the Guggenheim Helsinki Contest

Screenshot of All 1,715 Designs in the Guggenheim Helsinki Contest via http://designguggenheimhelsinki.org/

Earlier this month, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation released its six finalist designs for the Guggenheim Helsinki, a project that Finns have been debating since 2009. For people who hate contemporary architecture, the Guggenheim’s design contest is a godsend: The website features hundreds and hundreds of lazy renderings that have no context in Helsinki’s South Harbor, each one more fantastical than the next in a bid for the design jury’s attention. As a whole, the contest is bad for architecture: Only firms that can afford to work pro bono bother entering contests, which rules out the scrappy designers that a big net is meant to catch.

In the end, the jury picked five designs that are less offensive, at a glance, than the median contest entry, but the sum here is more heinous than the parts. (Although one finalist entry doesn’t appear to show a building at all.) How much time could a jury have afforded to each entry? Even at a scanty five minutes each, the jury would’ve needed to stay empaneled for days and days to sort through them all. It’s hard to think of a better way to pick a building designed to irritate its host.

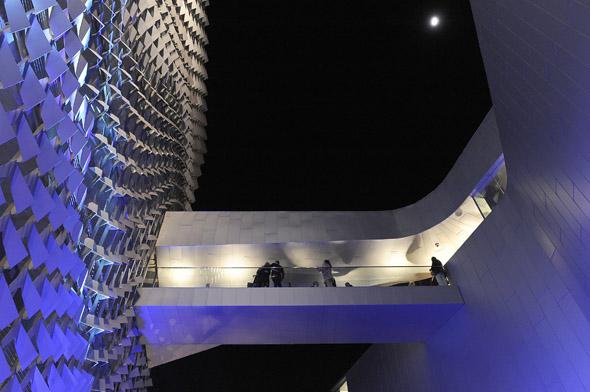

Emerson College Los Angeles (Morphosis)

Some people will tell you that Thom Mayne’s design for 41 Cooper Square was the nail in the coffin for the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York’s historically tuition-free and highly selective school of art, architecture, and engineering. Unable to make good on the $175 million loan that trustees took out to build this statement engineering building, the Cooper Union—free to all its students since the 19th century—started charging tuition this year.

It’s not the architect’s fault that the financial plan was a bad one. Still, to see Mayne build a similarly eye-grabbing building for the Los Angeles campus of Boston’s Emerson College raises red flags. Yet again, the crisis in higher education—with universities emphasizing the bells and whistles over fairly paid faculty at the expense of rising tuition—takes physical form in a Morphosis jam. “It’s like living in the Guggenheim,” one student told the Los Angeles Times, which tells you everything you need to know.

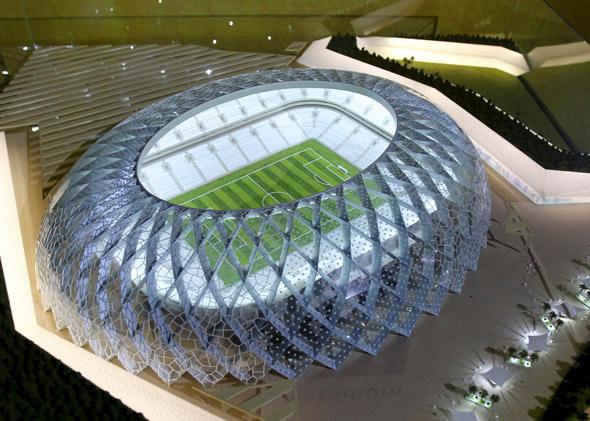

Al Wakrah Stadium (Al Wakrah, Qatar; Zaha Hadid Architects)

Photo by Fadi Al-Assaad/Reuters

New National Stadium (Tokyo, Zaha Hadid Architects)

Photo by Toru Yamanaka/AFP/Getty Images

Technically, Zaha Hadid cannot be blamed for the deaths of slave-labor workers in the construction of the stadium she’s designed for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, because that work hasn’t begun in earnest yet. The architect sued Martin Filler for laying the responsibility for workers’ lives at her feet in the New York Review of Books, and he took back his words. Work on the site began only in August, and construction does not gear up in full until next year.

Yet the internationally renowned architect might have responded to mounting criticism otherwise. In Qatar, some 1.4 million migrant workers are building the World Cup site from the ground up under miserable conditions. At the rate they are dying now, an estimated 4,000 workers will perish by the time the first match kicks off in 2022. Typically, it’s not plainly obvious in advance that hundreds of workers may die to fulfill an architect’s vision. She might have withdrawn her work from the project and suffered only a boost in her reputation as a human rights champion. Instead, she outlined a preemptive self-absolution of responsibility for the lives of the workers that will almost certainly be claimed in building the stadium.

After all, Qatar isn’t the only mega-stadium that Hadid has in play, as her firm is designing the Olympic stadium for the Tokyo Games in 2020. This stadium is controversial, too: Some of the greatest Japanese architects (Toyo Ito, Kengo Kuma, Fumihiko Maki, and Sou Fujimoto among them) say that her stadium is just too large for the scale of the neighborhood. These aren’t the simpletons reacting in shock to the vulva-shaped design of the stadium (and those critics are wrong: The world needs all the yonic architecture it can get). Professional courtesy might compel Hadid to revise her draft, but instead, earlier this month, she lashed out at her critics, calling a pantheon of Japanese designers “embarrassing” and “hypocrites.” In terms of design, neither of these stadiums is a hill worth dying on—either professionally or literally.

Florida Polytechnic University’s Innovation, Science, and Technology Building (Orlando; Santiago Calatrava)

The enormity of the problem with Santiago Calatrava’s transit hub at the World Trade Center is both easy to understate and hard to pin down. It cost nearly $4 billion in the end, although it was projected to cost half that, and it took twice as long to build it as was planned. Easy math, and yet even the full forensic report from the New York Times this month only scratches the surface of the bureaucratic missteps that have marred this project over the last decade.

But I choose the Innovation, Science, and Technology Building for Florida Polytechnic University as an even worse Calatrava project. It was reportedly completed on schedule and for just a fraction of the cost of the Ground Zero transit hub (although still slightly over budget). According to Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne—who reviewed the building in Architect magazine, where I used to work—this Orlando campus project might not be a fatal liability for the school, in the way that so many Calatrava projects are.

Except, of course, that it is an architectural temple built over green farmland to anchor a new campus for a far-flung commuter school, a project that violates possibly every tenet of good planning and design in 2014. The extraordinary arrogance of this design has to count as a debit for architecture, whether he finishes on time or not. (His bridges, on the other hand, are pretty cool.)

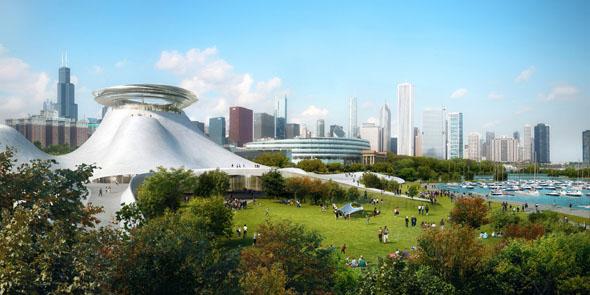

Lucas Museum of Narrative Art (Chicago, MAD Architects)

Courtesy of the Lucas Musuem of Narrative Art

Lucas Cultural Art Museum (San Francisco, Urban Design Group)

Screenshot from the Lucas Cultural Arts MuseumFinal Proposal, SF, Jan 17, 2014 - Urban Design Group via http://www.presidio.gov/

A long time ago (February), in a design contest far, far away (San Francisco), the Empire was dealt a crushing blow. The board of the Presidio Trust declined a proposal from George Lucas to build the Lucas Cultural Art Museum, a $700 million development that would have occupied eight valuable acres near Crissy Field. Later in the year, the Empire struck back: Lucas announced in June that he would park his Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Chicago instead.

What a difference four months make. Over the interim, Lucas jettisoned the museum designs that Urban Design Group had developed for the Presidio plan. That makes sense: The Presidio Trust had set forth strict design requirements in keeping with the Spanish Revival and Beaux Arts architecture of the area. According to notes in the final proposal, one of the early drafts from Team Lucas was rejected for being too monumental and unwelcoming.

For the Chicago museum, Lucas’ designers (Beijing-based MAD Architects) ran in the opposite direction. The museum, which will occupy land near Soldier Field, looks like the kind of ship that could do the Kessel Run in less than 12 parsecs.

No doubt, Ma Yansong is a talented architect. He’ll make an excellent (albeit controversial) contribution to Chicago’s world-class architecture. (While it’s especially sensitive to the landscape and lakefront, the building will occupy two parking lots that Chicago Bears fans presently use for tailgating, meaning that Lucas is practically inviting Da Bears to trash his building like a bunch of drunk Wookies.) The building itself is fine, an example of China’s “weird architecture,” which Chinese President Xi Jinping recently trashed. But could George Lucas care any less about it?

It’s a hopeless museum. Lucas’s gift store–ready collection of treacly illustration and fantasy memorabilia will be a huge detriment to the city. That’s not in any way the architect’s fault. But in the span of one year, Lucas pretty much admitted that his museum would fit just as well in a Colonial Revival building as it would in a design that’s Star Wars Modern. That’s not the biggest sin, but it’s not exactly a sign of great vision. For Lucas, apparently, design matters not.

One World Trade Center (New York, David Childs)

The other major component of the World Trade Center that finished this year is One WTC, and it may stand as the worst project of a generation. The problems with this building are as storied as those of the World Trade Center transit hub. The architect of the erstwhile “Freedom Tower,” David Childs, can’t be blamed for all those problems. The elegant 7 World Trade Center stands nearby as proof that he can do better, as do his preliminary designs.

If One WTC is a “cautionary tale,” as New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman puts it in his review, it’s a warning against design by committee. Kimmelman writes that the public didn’t have enough say in the design of the building. Rather, developers had too much say. The process whittled away at the tower’s spire until it was merely an antenna; the system revised and revised until the building’s four faces were all identical, and all plain.

In the strictest sense, there were worse buildings in 2014: hundreds of drive-thrus and strip malls in an ever-expanding universe of American sprawl. Instead, the worst of the best buildings proved that even starchitecture is subject to the same powerful forces as everything else.