Over two days of testimony before Congress earlier this month, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg dodged a litany of questions from lawmakers about how the data of 87 million Americans ended up in the hands of voter profiling firm Cambridge Analytica.

The spectacle put a spotlight on the company’s murky data-collection and sharing practices, and sparked a much-needed discussion about if and how to hold companies accountable for their handling of user data.

However much deserved, Facebook has, so far, born the brunt of public scrutiny for what has unfortunately become standard practice for web platforms and services. As the Ranking Digital Rights 2018 Corporate Accountability Index—an annual ranking of the some of the world’s most powerful internet, mobile, and telecommunications companies that was released this week—shows, companies across the board lack transparency about what user data they collect and share, and tell us alarmingly little about their data-sharing agreements with advertisers or other third parties. (Disclosure: I work with RDR and worked on this report. RDR is a project of New America, which is a partner with Slate and Arizona State University in Future Tense.) The majority of the 12 internet and mobile companies we evaluated for this index also failed to give users clear choices about how their data is used, or options to control how they are being tracked and profiled, and why.

In practice, this means the intrusive data harvesting practices that led to the Cambridge Analytica scandal could be far more common, and more pervasive, than we know. This not only exposes the massive amounts of intimate information these companies collect on us to a bevy of privacy and security risks, but also likely sets us up for more attempts by bad actors to use our data against us—as we’ve seen with political ads aimed at spreading propaganda and fomenting division. That is, unless we’re able to hold companies accountable for these bad practices and pressure them to reform.

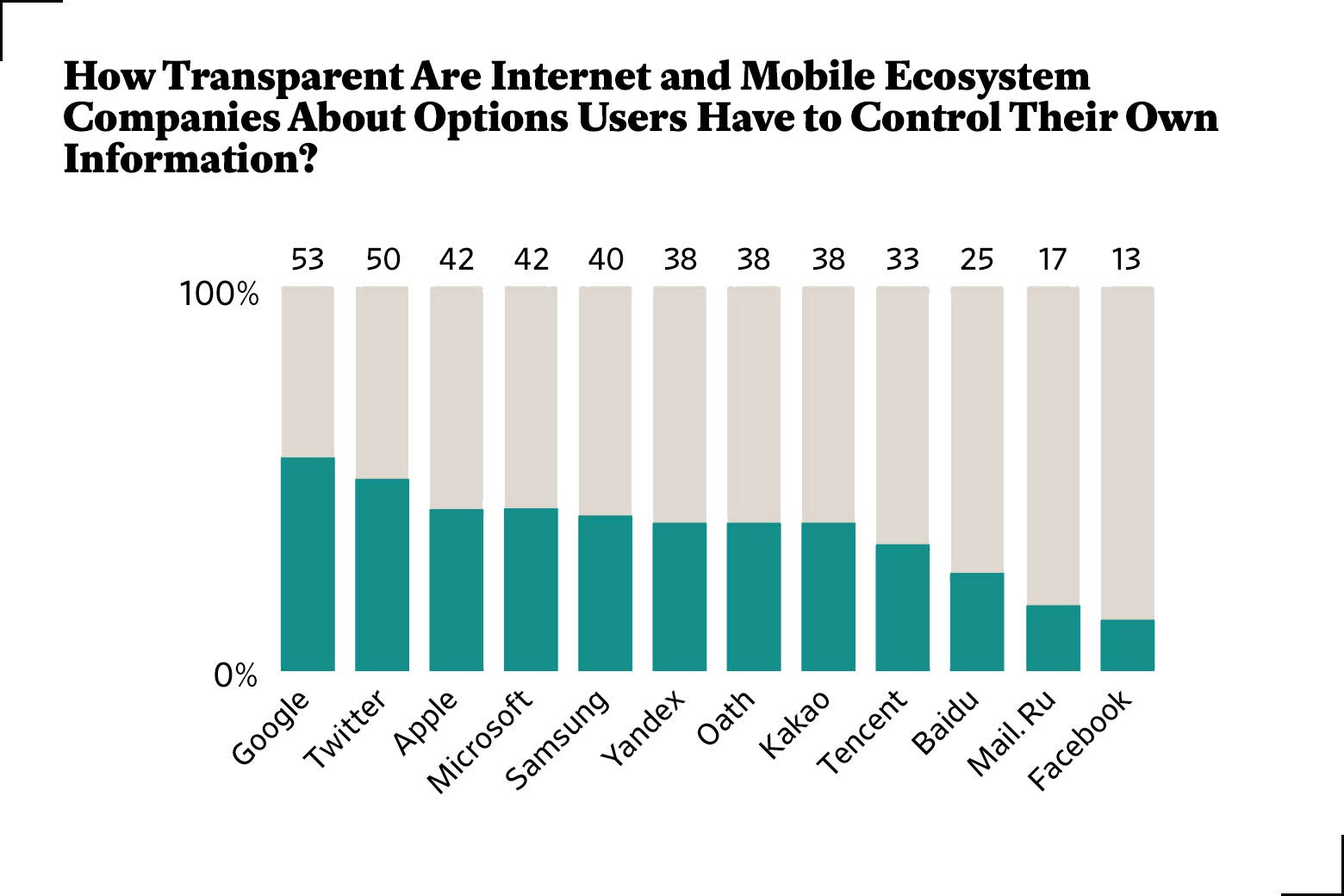

Not surprisingly, our analysis found that Facebook was less transparent than the five other U.S.-based internet and mobile platforms—Apple, Google, Microsoft, Oath (formerly Yahoo), and Twitter—about its handling of user data, such as what information it collects, shares, with whom, and why. The company also offered fewer disclosures than any other internet and mobile platform in the entire index, including two Chinese companies and two Russian companies, about options users have to control what’s collected about them and how that data is used. Over the past several weeks, Facebook has clarified some options users have to control their data, but these measures have not fundamentally changed the company’s existing policies.

Facebook’s poor showing on these questions is notable given the current controversy, but no company fared especially well on these issues. Because these companies are collecting such personal data on you—potentially who you’re messaging and when, your browsing and search history, your online purchases, your public profile information, among other details of your digital life—they should be transparent about what they’re collecting, how they’re share it with advertisers and third parties, and how it’s being used to serve you targeted ads. Ideally, companies should give users a clear choice to “opt in” to receive these targeted ads, rather than having the sometimes-creepy personalized content served by default. They should similarly give users options to control what personal data the company collects and how it’s allowed to be used and shared.

But our research shows that most internet and mobile companies we evaluated, including Facebook, only gave users the option to opt out of receiving interest-based ads, should they wish to do so and manage to navigate through often-labyrinthine settings pages to toggle them off. None clearly informed users if and when they were being automatically tracked and profiled. Nor did any appear to operate on the ideal “opt-in” model.

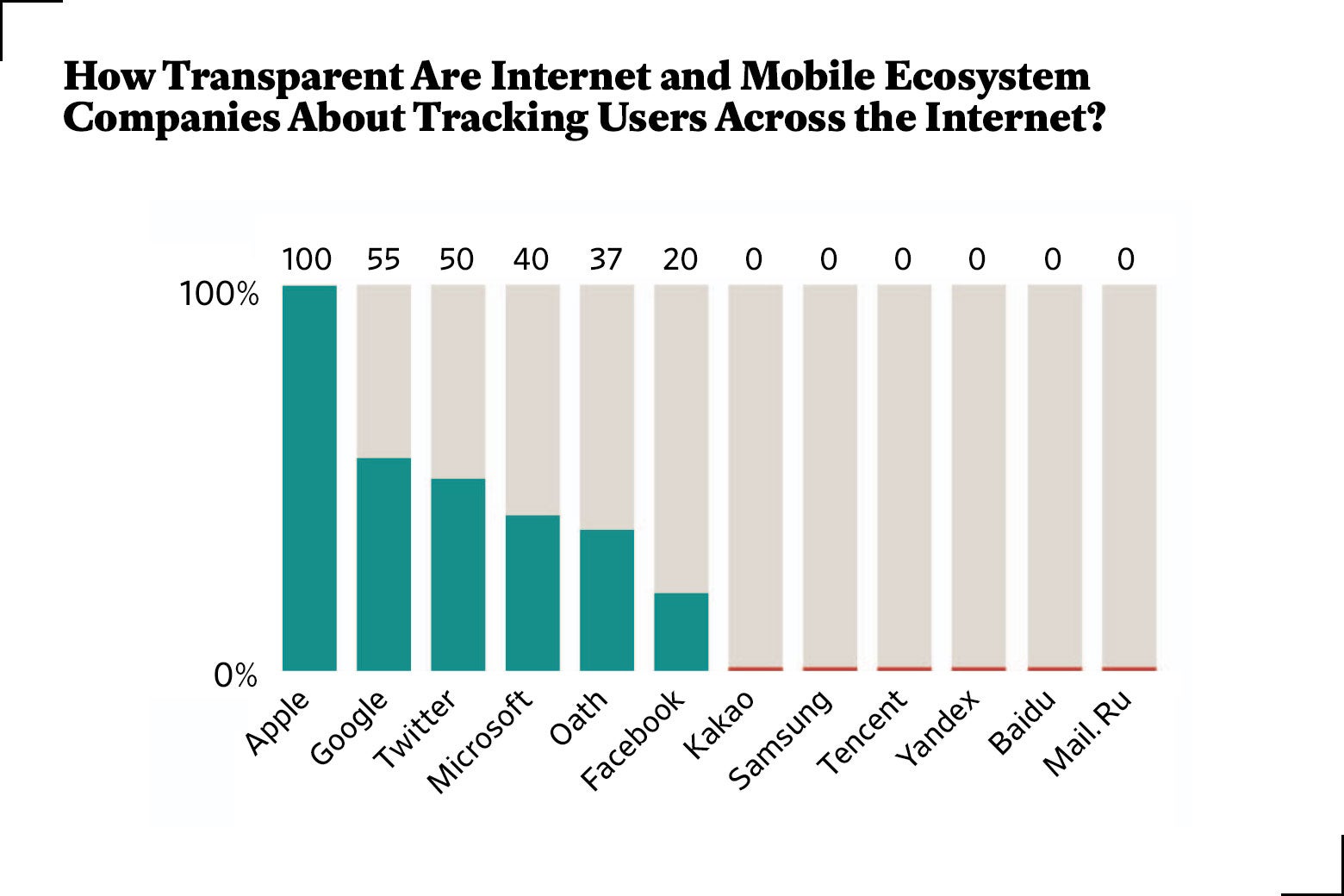

This problem goes beyond corporations recording what users do on their platforms. The companies we evaluated also proved especially evasive about clearly advising users if and how they track users across the internet, whether it be deploying cookies to follow and collect data on individuals across websites and devices, or casting similar data-collection nets via widgets or plug-ins, like social media buttons, or via other types of web-tracking tools embedded on other websites. For instance, Google Analytics, a tool that records website visits and feeds that information back into the company’s ad-targeting system, is embedded on a vast majority of the internet’s most-visited websites.

To platforms like Google and Facebook, these types of tracking tools and practices are worth big bucks. Combined, the pair, nicknamed “digital duopoly,” controls nearly 60 percent of total U.S. online ad investments—largely because the pair can sell more highly-targeted ads on systems that use the detailed individual behavior and preference profiles they’ve been able to amass (including on people who aren’t even registered on the platforms). But the companies’ lack of forthrightness about these practices means they’re making massive profits on tracking, recording, and sharing our information without meaningful consent.

It’s an issue that was on full display during Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional testimony, when he deflected multiple inquiries from representatives asking him whether Facebook tracks people around the web who aren’t logged into Facebook. As Slate’s Will Oremus pointed out in his piece detailing the most dishonest answers Zuckerberg gave, the CEO mostly deflected such questions. “It would probably be better to have my team follow up afterward,” he answered to one. To another: “I’m not—I’m not sure of the answer to that question.” “Really?” the senator replied. “Yes,” said Zuckerberg, despite the fact it’s been the subject of lawsuits and is buried in Facebook’s own user policies. (In fairness, his team did follow up on this question in a post on the company’s “Hard Questions” blog, and has since updated its privacy policy and ad settings to make them easier to navigate.)

But, once again, Facebook wasn’t the only internet or mobile company that lacked clear disclosure about whether and how they track users across the internet. Ten other internet and mobile systems that we evaluated in our ranking—including Google, Microsoft, and Twitter—either said little about these tracking policies or provided no information at all. Only Apple clearly stated that it does not track users on third-party websites.

These results should come as no surprise to rights groups and experts, many who have warned of the privacy and human rights risks posed by surveillance capitalism, a goliath industry of monetizing user data that has flourished with little oversight, accountability, or public awareness. Many of world’s most powerful companies—including Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft—rely on this advertising-based revenue model to varying degrees. For those who haven’t had the time to read the legaled-up language of every single privacy policy we encounter (which, considering Carnegie Mellon researchers estimated it would take the average user the equivalent of 76 work days per year to do, is most of us), and even for people like me who do it for a living and still find disclosure gaps, the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal managed to shed a bit of light on the otherwise obscure relationships between some tech companies and advertisers. But it only exposed a sliver of the harm and potential harm wrought by the opaque profit-over-privacy business model that continues to dominate tech.

In the U.S., calls for tougher regulations are growing louder. Policymakers and the public seem fed up waiting for tech companies to rein themselves in. Yet even in the European Union, often looked to as a model for the stricter data protection rules it imposes on companies, EU-based telecommunications companies measured still lack transparency about key policies affecting users’ privacy, as our index shows. Many privacy advocates now see the regional body’s forthcoming General Data Protection Regulations, or GDPR, (the reason you’re getting notifications on sites like Twitter about privacy policy changes starting May 25), as a step in the right direction. The rules require companies to give users clear options to control the collection and use of their personal data, and include stricter standards about transparency. Yet there is no telling how the GDPR will be enforced, and whether or how companies outside the EU will comply. The GDPR and new proposed legislation in the U.S., like Social Media Privacy Protection and Consumer Rights Act of 2018, may help establish some baseline data controls and transparency for users. Yet it’s not hard to imagine these powerful companies using their compliance with these minimum legal standards as a cover to say “we’re doing everything we can,” while continuing with a host of shady but profitable data-harvesting practices.

Whether this is a moment of reckoning remains to be seen. What is certain is that that unless tech companies work to improve transparency and accountability about what they do with user data, public trust in these companies will continue to erode. But given that most major companies are at present are not telling people enough about their data collection and tracking practices, it’s likely that, in the meantime, we’ll see more of our personal data caught up in controversies like the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica fallout.