Facebook has been widely ridiculed for trying to assess the trustworthiness of news outlets via a simple two-question survey of users. A new working paper from researchers at Yale University suggests that might not be ridiculous after all—although it does raise an interesting question about the details of Facebook’s methodology.

The paper highlights both the promise and pitfalls of Facebook’s project to build a trustworthiness ranking into its news feed algorithm. That’s part of the social network’s big new push to stop amplifying fake news and partisan pandering, which have helped to polarize public opinion, destabilize democracies, and facilitate foreign meddling in elections.

In the study, published Tuesday, psychologists Gordon Pennycook and David Rand presented more than 1,000 Americans (via Mechanical Turk) with the same two-question survey Facebook plans to use. For 60 news websites selected by the authors, it asked respondents first whether they recognized the outlet, and second how much they trusted it: not at all, barely, somewhat, a lot, or entirely. Of the 60 sites the authors chose, 20 were mainstream media outlets, 20 were “hyperpartisan” outlets, and 20 were “fake news” hoax sites.

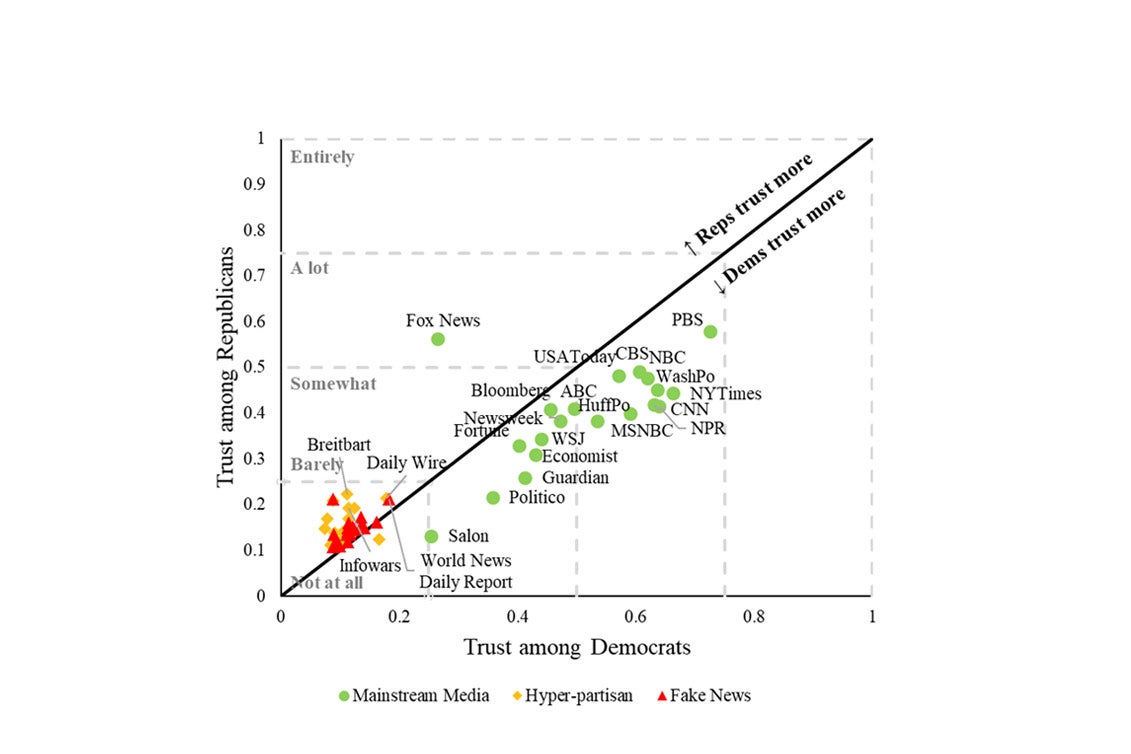

Republicans and Democrats differed on just how much they trusted each one, but on average, they had no trouble rating them all higher than sites that actually traffic in fake news. (The sole exception was left-leaning Salon, which was trusted less by Republicans than the likes of Breitbart or Infowars, though far more so by Democrats.)

In at least one plausible interpretation of the survey results, the respondents distinguished the credible outlets from the sketchy ones with near-perfect accuracy. Nineteen of the 20 mainstream news outlets in the sample were trusted more by both Democrats and Republicans than any of the other 40 outlets were trusted by respondents of either party. That includes sites such as the New York Times and CNN, which Donald Trump has famously branded as “fake news,” along with somewhat more partisan mainstream outlets such as Fox News and MSNBC.

If you find this surprising, you’re in good company: Rand, the study’s co-author, told me he too had initially laughed at Facebook’s two-question survey, before deciding to test it out. “What this suggests is that people are actually not nearly as bad at knowing what is a legitimate news outlet and what is not than we might have pessimistically assumed,” he said.

Before we declare Facebook’s survey an ingenious success, however, there are some important caveats.

First, the study’s authors made survey respondents’ job easier by choosing relatively clear-cut examples of reputable (e.g. PBS, CBS, and the Washington Post) and nonreputable (e.g. usasupreme.com and pamelageller.com) news sites. There are a few edge cases in their sample, such as the conservative Daily Caller (which they classify as hyperpartisan), the progressive Daily Kos (which they also classify as hyperpartisan), and liberal Salon (which they classify as mainstream). But the full set of possible news sources on Facebook includes far more publications that probably fall somewhere in between those two categories. The nonprofit Mother Jones, for example, has a clear progressive viewpoint, but also high journalistic standards. Would conservatives say they trust it more than, say, conservativedailypost.com (a fake news site)?

Then there is the question of new or lesser-known outlets. The mainstream sources in the Yale study are all relatively established and widely known. The results leave unanswered the question of how respondents would rate newer publications such as Splinter, the Outline, or the Federalist. It also would have been interesting to see how they rated BuzzFeed, which produces some top-flight journalism but also a lot of listicles, quizzes, and other fluff.

But the biggest caveat to the study’s findings is this: To get the clean results described above, you have to interpret the survey data differently than Facebook is planning to.

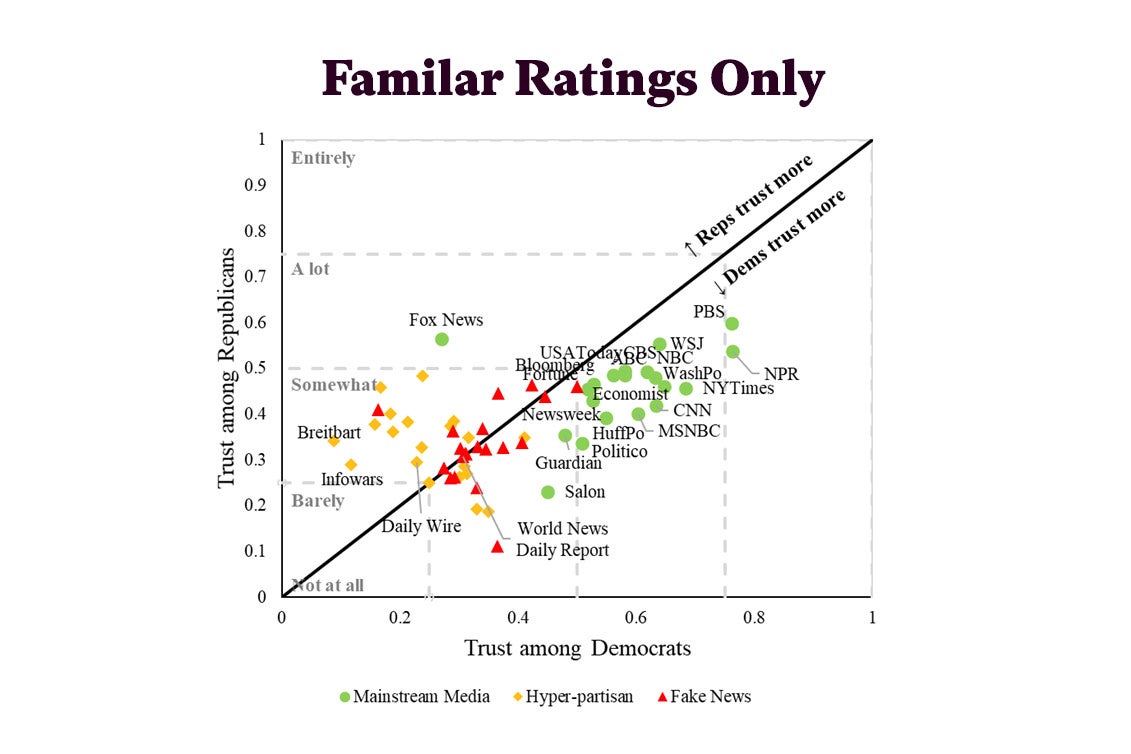

A two-question trust survey sounds simple, but as I explained in January, there are more possible ways to implement it than you might think. Facebook’s head of news feed, Adam Mosseri, told me on Twitter that the company will only consider trustworthiness ratings for a given publication from users who first indicate that they’re familiar with that publication. In other words, if a user says she’s familiar with Breitbart, Facebook will then count her response to the second question about how much she trusts it. But if she says she isn’t familiar with Breitbart, then Facebook will discard her answer to the trust question.

On an intuitive level, that makes sense. You wouldn’t want people rating publications they’ve never heard of. Or would you?

Surprisingly, the Yale study finds that including the trust ratings from people unfamiliar with a publication actually yields more accurate results, assuming the goal is to sift mainstream sources from fringe sites. The promising findings in the first chart flow from that methodology. The authors also produced a second chart using Facebook’s method, and the distinction between credible and sketchy sites in that one is a lot muddier.

Here, several hoax sites—including news4ktla.com, thenewyorkevening.com, and now8news.com—outperform mainstream sources in the trust ratings. How could that be?

The authors’ theory is that respondents’ unfamiliarity with a source is actually a strong signal that it’s not credible. In other words, if you’ve never heard of a news outlet, you’re probably going to be skeptical of its legitimacy—and in most cases, your skepticism will turn out to be justified. On the other hand, users who say that they are familiar with sites such as news4ktla.com or now8news.com are more likely to be the same ones who are getting duped by fake news from such outlets. So if you only count their trust ratings, you’re going to significantly overrate the credibility of fake news sites.

Facebook confirmed to me that it has no plans at this point to consider the trust ratings of people unfamiliar with a given site, despite the Yale study’s findings. That’s understandable. The Yale methodology may be effective in sifting out fake news sites, but it doesn’t feel quite fair to penalize sites just because people aren’t familiar with them. Specifically, that approach seems likely to punish newer and smaller sites, regardless of their journalistic standards.

So where does that leave us? The study’s findings are still encouraging overall, insofar as they demonstrate that even a simple survey can effectively differentiate between real and fake news sites, depending on how it’s implemented.

At the same time, they make clear that the results are likely to be imperfect, and that some sites are likely to be undeservedly amplified or unjustly suppressed in Facebook’s news feed, no matter what methodology it uses. The best hope for reputable news sites on Facebook remains that the company will continually test and refine its ranking system. Better yet would be for Facebook to open up its methodology so that academics, media outlets, and the public can scrutinize it for themselves. It’s one thing for the algorithm to be transparently unfair; it’s far worse for it to be both unfair and opaque, because it forecloses the possibility of constructive criticism.

In the end, it’s hard to escape the fundamental contradiction at the heart of Facebook’s project, which I and others highlighted at the very outset. In short, Facebook is trying to answer a subjective question—how credible are various news sources?—without making any subjective judgments itself. That’s literally impossible, as the Yale study highlights: Even the question of how to interpret the data from a two-question survey requires subjective judgments, which have a major impact on the results. As Rand put it: “Crowdsourcing just kicks the subjectivity one rung down the process, which is what do you do with the ratings.”

It seems that, for now at least, Facebook would rather hide its subjective judgments within the bowels of an opaque survey methodology than come right out and acknowledge them. That might help to insulate it from partisan criticism—at the cost of not quite solving the problem.