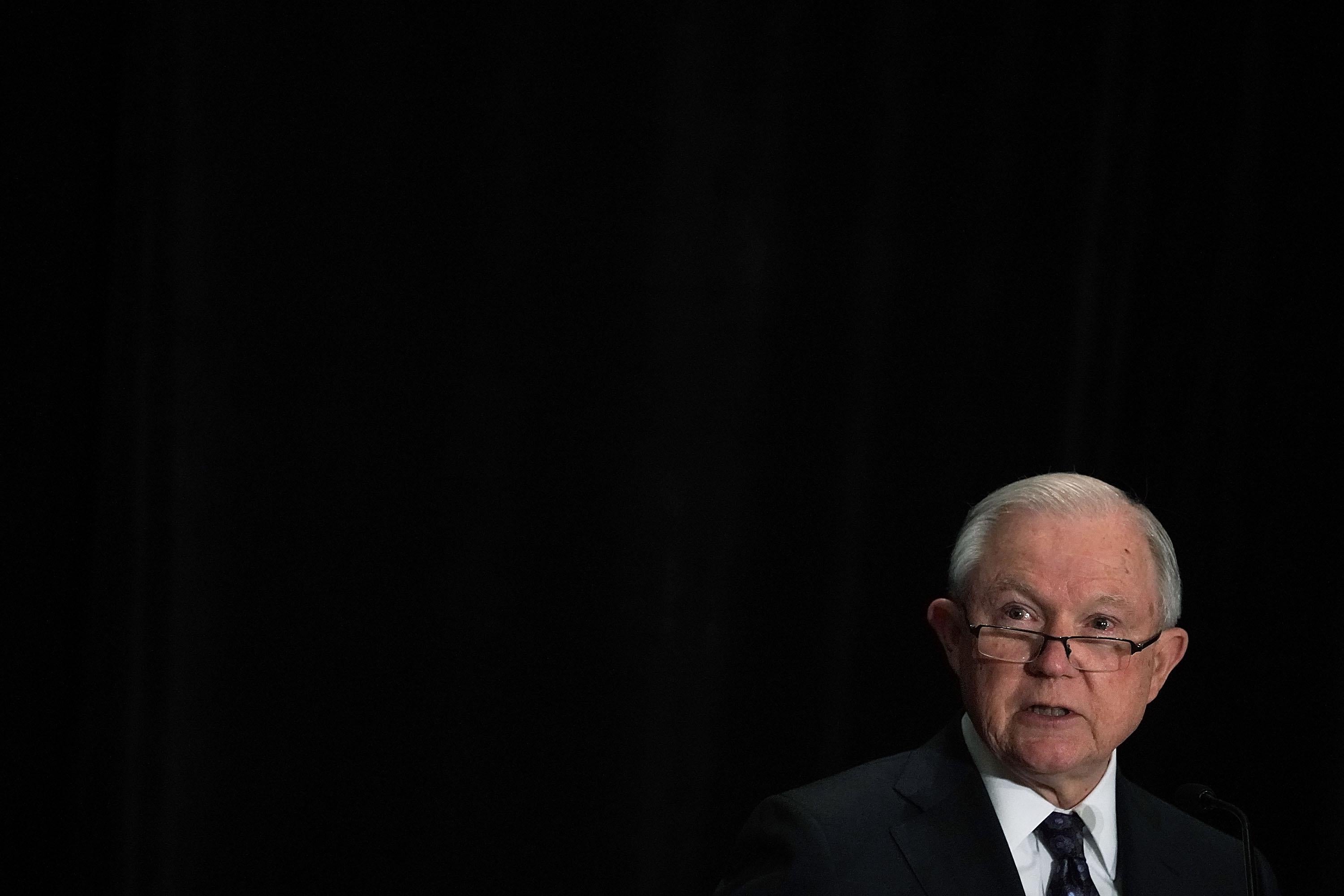

Attorney General Jeff Sessions ruled on Monday that most victims of domestic violence may not apply for asylum in a decision that is likely to condemn thousands of women to brutality. His ruling overturns four years of precedent permitting abuse victims to obtain asylum in the United States. Immigrants who fled to the U.S. to escape domestic violence may now be deported back to their home countries—even when they face near-certain torture and death.

Sessions’ decision in Matter of A-B- revolves the proper interpretation of asylum rules. Under federal statute, asylum-seekers may receive relief if they show they were persecuted on the basis of at least one protected trait: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or “membership in a particular social group.” The Board of Immigration Appeals has long held that an individual fits into that last category if her “social group” shares a “common immutable characteristic” that can be “defined with ‘particularity’ ” and is “socially distinct within the society in question.”

In 2014’s Matter of A-R-C-G-, the board considered the case of Aminta Cifuentes, a Guatemalan asylum applicant. In Guatemala, Cifuentes’ husband beat her weekly, raped her, and once poured turpentine on her skin in an effort to light her on fire. Although Cifuentes called the police, law enforcement declined to help her, explaining that they would not interfere in a marital relationship. Her husband threatened to murder her if she kept calling the police or left him.

In a landmark decision, the board found that Cifuentes and other spousal-abuse victims could apply for asylum. It first wrote that these women share two immutable traits: their sex (female) and their marital status (unable to leave their spouses). Then it noted that each element of the group can be “defined with ‘particularity’ ” as “married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave their relationship.” The board explained that “a married woman’s inability to leave the relationship may be informed by societal expectations about gender and subordination, as well as legal constraints regarding divorce and separation.” And it found that these women are “socially distinct” because “Guatemalan society” is distinctly unwilling to protect their lives and well-being. (For instance, the police regularly allow them to be raped and murdered by their husbands.)

A year later, the board expanded this precedent to include women in domestic relationships, not just legally married women. Under these decisions, immigrants hoping to escape violent partners were not guaranteed asylum in the U.S.—but they had a good chance of obtaining it, and could not be summarily deported back to their abusers. Asylum applicants still had to prove their status as abuse victims unable to leave their partners, and that this status was “at least one central reason” for their persecution. Still, the law was on their side, and they stood a fighting chance of winning the right to remain in the U.S. lawfully.

That all changed on Monday. A quirk in immigration law allows the attorney general to single-handedly reverse a decision by the Board of Immigration Appeals, and Sessions exploited that power to overturn the precedents permitting domestic abuse victims to apply for asylum. In his opinion, Sessions wrote that, to qualify for asylum, a “particular social group” must have more in common than their shared persecution. Abuse victims, he held, do not generally satisfy this requirement, because they are defined by their “vulnerability to private criminal activity.” Moreover, Sessions found, these victims did not suffer true “persecution.” Persecution is “something a government does,” and to obtain asylum, an abuse victim must now prove that her government will not help her.

Finally, Sessions held that abuse victims are not typically persecuted “on account of” their membership in a particular social group. Citing Cifuentes’ case, he wrote that the board “cited no evidence that her ex-husband attacked her because he was aware of, and hostile to, ‘married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave their relationship.’ ” Rather, “he attacked her because of his preexisting personal relationship with the victim.” Thus, Cifuentes was not truly “persecuted,” and neither she nor similarly situated abuse victims may claim asylum.

Sessions’ decision is highly debatable as a matter of law. Many of his conclusions are drawn from a concurring opinion that frames the federal asylum statute in the most stringent way possible. His central holding is largely a matter of policy preference recast as a legal command through selective quotations from scattered appeals court rulings. Regardless, it is now law, and it will almost certainly prevent most abuse victims from winning asylum. Now, thanks to Sessions, these victims must show that their governments “condoned” private violence against them, or “demonstrated an inability” to protect them. Very few people will be able to present evidence that satisfies this extraordinarily high bar. (Sessions’ draconian definition of persecution also has dire ramifications for other groups, including victims of gang violence and anti-LGBTQ brutality, who often struggle to prove that their governments condone their persecution.)

It is impossible to separate Monday’s decision from the Trump administration’s policy of separating families seeking asylum at the border. The courts appear poised to restrict the administration’s ability to break up the families of legitimate asylum-seekers; Sessions’ ruling shrinks this category, allowing immigration officials to expedite the deportation of women and children fleeing domestic violence. And it further endangers the lives of immigrants who have risked everything to escape torture, torment, and murder. The Trump administration’s immigration policy now seems designed to inflict maximize cruelty on the most vulnerable among us. Instead of aiding the persecuted, the United States is persecuting the victims.