On Monday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Janus v. AFSCME, a challenge to the idea that public-sector unions can collect fees from nonmembers in 22 states. The court may as well skip the charade of arguments altogether. There is simply no question how the justices will rule in Janus: After Justice Antonin Scalia died in 2016, they divided 4–4 on this exact question. Since then, Republicans installed Justice Neil Gorsuch on the court, and no one seriously doubts that he will come through for the party that kept his seat open for a year.

What’s interesting about Janus, then, is not its inevitable outcome, but the role that it will play in furthering the Republican agenda. Public-sector unions have long helped Democrats win elections and implement progressive policy, counteracting the influence of conservative corporate electioneering. Legislative assaults on unions helped weaken the Democratic Party. The judicial blow could cripple it.

Janus marks the logical endpoint of a laughably spurious constitutional theory. In 1977’s Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, the Supreme Court upheld agency fees in public-sector employment. Unions collect these “fair share” fees from nonmembers to support collective bargaining and cannot use them to subsidize political activities. The Abood court held that it is perfectly constitutional for public-sector unions to compel nonmembers to pay these fees: Because they benefit from the contracts that are achieved through collective bargaining, the court reasoned, they can be forced to help cover the costs of those negotiations.

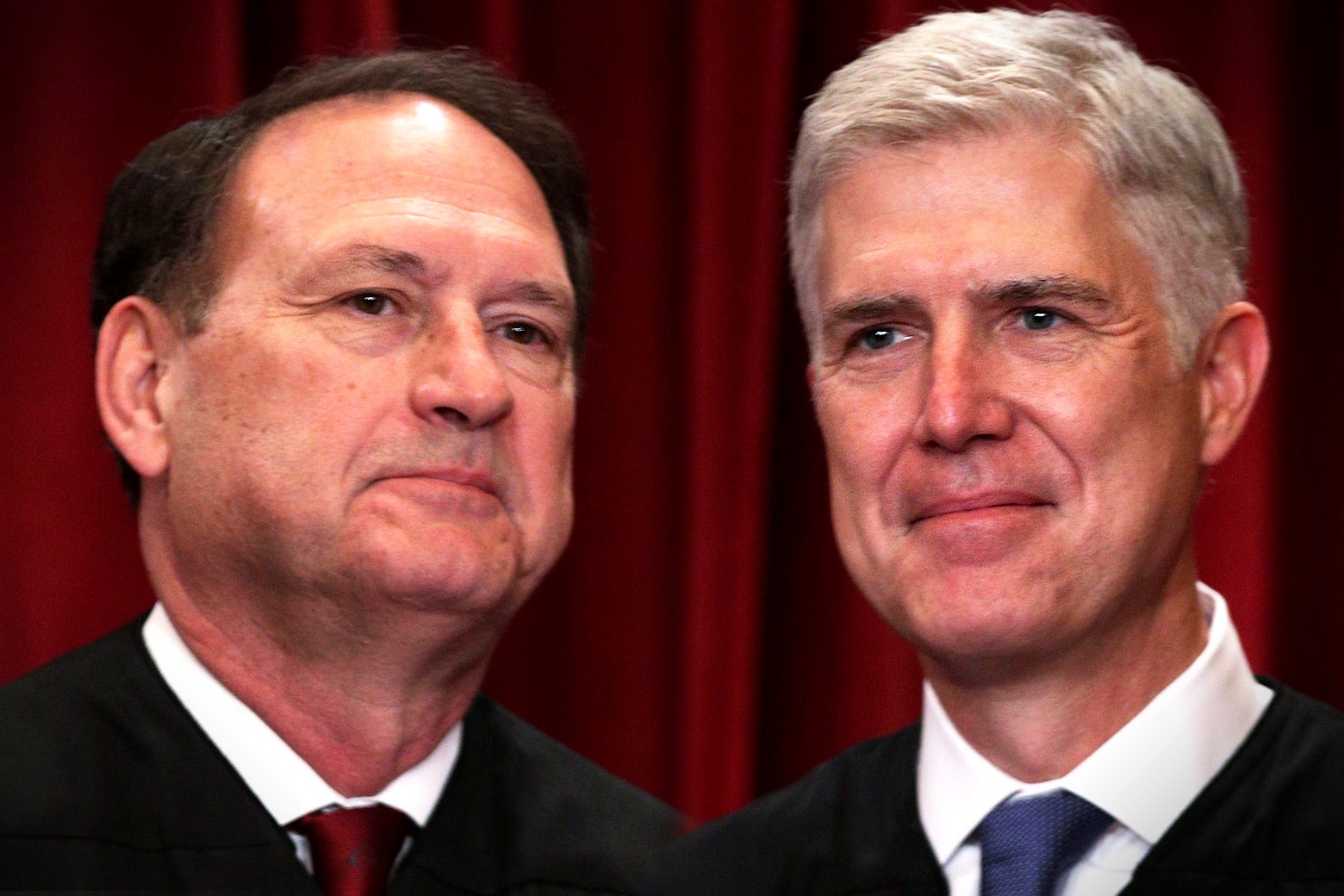

Today, 22 states and the District of Columbia permit public-sector unions to collect agency fees. But in recent years, the Supreme Court’s conservatives have declared war on the decision. In 2014, Justice Samuel Alito essentially declared in Harris v. Quinn that Abood was wrongly decided and should be overturned. Alito asserted that mandatory agency fees constitute “compelled speech” and therefore violate the First Amendment’s guarantees of free expression and association. According to Alito, bargaining for a labor contract is actually political activity, because nonunion workers may hold an ideological opposition to benefits like health insurance and overtime pay.

This framing of unions reflects a profoundly cynical vision of workers’ rights, turning free riders into “compelled riders” who are forced to accept benefits that they reject on political grounds. It also has no real constitutional basis. Eugene Volokh, a right-leaning libertarian who generally opposes unions, contributed to an amicus brief explaining why Alito’s theory is completely incorrect under an originalist understanding of the First Amendment. “Compelled subsidies of others’ speech happen all the time,” the brief explains, “and are not generally viewed as burdening any First Amendment interest.” The government can spend tax dollars on speech with which taxpayers disagree; it can compel lawyers to pay state bar dues, then use the money to promote messages that some lawyers detest; it can even collect a special assessment on teachers to promote education policies that some teachers dislike. Of course it can also let unions collect fees from nonmembers to cover contract negotiations.

Conservative originalist scholar Michael Ramsey agrees with Volokh. The Supreme Court will not. Shortly before Scalia’s death, the court took a case identical to Janus designed to outlaw agency fees in public-sector unions. After he died, the court deadlocked. Months after Gorsuch replaced him, the court agreed to hear Janus. The Trump administration has weighed in against unions. We know how this case will end; the dark-money group that spent $17 million to put Gorsuch on the court will receive a return on its investment.

While the legal theory upon which Janus is based is specious at best, the political theory is brilliant. The Republican Party has done an excellent job persuading the court’s conservative appointees that the thrust of the First Amendment is that constituencies who do not support the Republican Party should not have political power. In Shelby County v. Holder, the court paved the way for massive voter suppression throughout the South by gutting the Voting Rights Act; Republican legislatures quickly passed voter suppression laws, and black turnout dropped dramatically. In Citizens United v. FEC, the court unleashed hundreds of millions of dollars in “super PAC” spending, paving the way for Republican electoral victories. That decision claimed to benefit both corporations and unions—but ever since, the court has further empowered corporations while continually hobbling unions.

Republicans have long acknowledged that they see public-sector unions as a key threat to their political agenda. The conservative American Legislative Exchange Council has seen teachers unions as a major impediment to their agenda for nearly half a century, complaining that the “most effective lobby in the state legislatures … was the National Education Association.” ALEC has worked to undermine teachers unions with “paycheck protection” laws, which require unions to keep separate funds for political activities. ALEC’s model governor, Scott Walker, famously worked to limit collective bargaining, and as soon as Republicans gain political power in statehouses, unions come under fire. Recent research on ALEC’s war on public-sector unions suggests that it has indeed been effective. The onslaught of conservative attacks has reduced union dues, demobilized public-sector union workers, and even led to lower expenditures on education.

New research by political scientists James Feigenbaum, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, and Vanessa Williamson gives us an idea of what will happen when the Supreme Court imposes so-called right-to-work laws from the bench. Right-to-work laws allow workers to benefit from unions’ collective bargaining without having to pay any union dues at all and are often paired with limits on public-sector organizing. (A recent right-to-work law in Kentucky also banned public sector workers from striking, an infringement on constitutional rights the courts have not seen fit to strike down.) The Janus decision, which would bar mandatory agency fees in all public sector unions, is basically a right-to-work law for public employees in every state.

To study the effect of these laws, Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez, and Williamson examined counties that share a border between two states, one with right-to-work laws and one without. These county pairs share demographic, political, and economic similarities. The authors found that the passage of right-to-work measures decreased Democratic vote share by 2 to 3 percentage points in both presidential and down-ballot elections—enough to have swung Michigan and Wisconsin to Trump in 2016. They also found that these laws reduce turnout and demobilize blue-collar workers, with blue-collar workers less likely to report receiving a contact about voting in right-to-work states.

Right-to-work laws also increase Republican power in state legislatures and shift policy to the right. Using historical data, Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez, and Williamson estimate that right-to-work laws lead Democrats to control fewer seats than they otherwise would, by 5 to 11 percentage points. In addition, the authors find that after the passage of right-to-work laws, state policy shifts to the right, even when Democrats control the legislature.

Combine these political ramifications with the astoundingly weak constitutional arguments, and Janus looks like a flagrantly partisan vehicle through which conservatives can kneecap the Democratic Party. With Gorsuch’s fifth vote, the court will reverse a 41-year-old precedent that has allowed progressives to mount meaningful opposition to GOP voter suppression and corporate electioneering. Janus isn’t really a case about the First Amendment. It’s a test to see how far certain justices will go in carrying out the Republican Party’s agenda.