After it became clear on Friday that Democrats and Republicans were not going to reach an agreement to keep the government open, there was some chatter around the Capitol that we might just be facing a “weekend shutdown”—a couple of days to finalize some tentative agreement that could cruise through both chambers in time for non-essential federal workers to return to the office on Monday morning.

How precious that thinking was.

Both the House and the Senate went into session on Saturday—for press conferences, meetings, speeches, and some procedural votes—and they did not leave with an agreement, or any apparent progress towards one. The impasse, it seems, will have to be resolved by the public.

Republicans and Democrats couldn’t even agree on a proper accounting of what transpired on Friday.

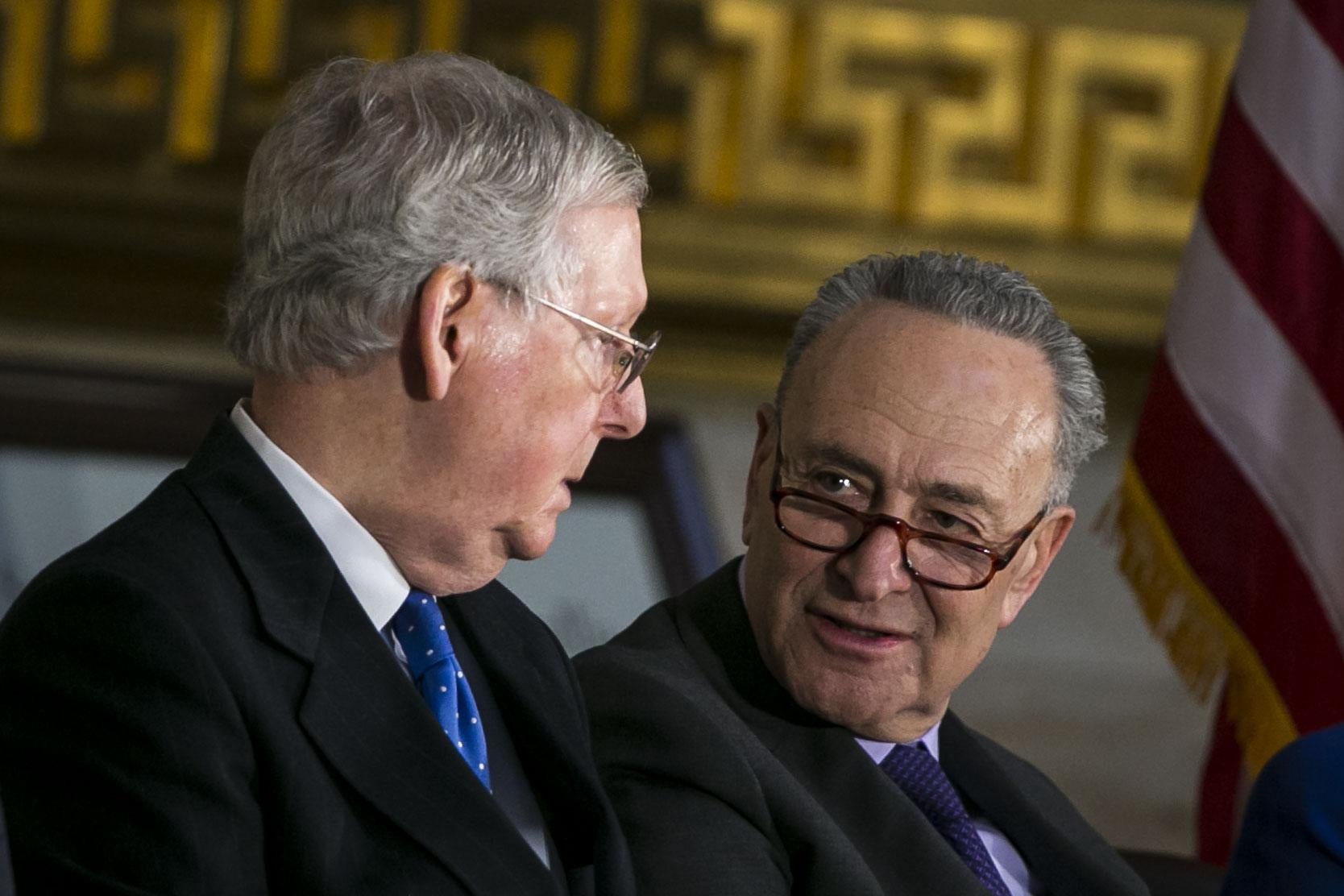

The Senate Democratic leader, Chuck Schumer, has said that he offered to consider the full spending request for President Trump’s promised border wall when the two met on Friday, and that the president later backed out on some tentative agreements once his advisers, including Chief of Staff John Kelly, got to him. But in a briefing Saturday, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told a different story: The president asked Schumer for $20 billion to build the wall, and Schumer rejected it, only offering the original $1.6 billion request outlined in the White House’s 2018 budget.

“We absolutely did not reject the full funding request,” a senior Democratic aide told me. “Schumer and Trump agreed by the end that they were close enough on everything that they should pursue a short term CR to facilitate a deal, so nothing was agreed to but they were in good shape on an overall framework. Then Kelly started to unravel it.”

There’s also a dispute over why a deal failed to come together during the frenzied two-hour Senate vote Friday night. The proposal included a bill to fund the government through Feb. 8, rather than Feb. 16, as well as a commitment to move a bipartisan immigration bill through the Senate and the House—either in a stand-alone vote in the next few weeks or attached to the Feb. 8 spending bill. The Senate Democratic Whip, Dick Durbin, claims that when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and House Speaker Paul Ryan spoke on the phone to discuss this, Ryan rejected it outright. (There was a moment on the floor last night when McConnell walked back into the chamber from a call, said something to Durbin, and Durbin rolled his eyes and shook his head.) McConnell spokesperson David Popp described Durbin’s characterization as “laughably false,” and said “there was no deal at any time that was blown up by Speaker Ryan. Period.” Ryan’s spokeswoman, AshLee Strong, said that “the speaker was not part of any deal or involved in any negotiations.”

Whether Ryan formally tanked a “deal”—there’s some wiggle room here—is a technical point. Everyone understands the dynamic. House Republicans do not want to take up the Senate’s bipartisan immigration bill. If they did, the Senate could wrap that and all of the other loose ends quickly. If House leaders brought up the Senate’s immigration bill, it could pass the House with mostly Democratic votes, over the objections of conservative members. Such a move could invite a challenge to Ryan’s speakership from the right—especially if the Senate bill doesn’t currently enjoy the president’s support. This, in very condensed form, is the dilemma: Most Senate Democrats will not vote for a spending bill until there’s a path for getting protections for Dreamers passed in both houses, and House Republicans and the White House are saying that they will not negotiate on immigration while the government is shut down.

So how does the government reopen? The answer to that won’t be known for a few days.

First, the public must decide who’s to blame. As the shutdown lingers and more people pay attention, polling will more clearly reveal which party is “losing.” The losing side will then sue for peace, and then it’s just a matter of negotiating the terms of surrender. Since the “winning” side has zero incentive to save the losing party, the surrender offer will likely be nothing.

So much of the punditry about shutdowns is about how it will affect the midterm elections, and so little of it is about the very important items that are at stake. But the political fears are just a spur for resolving a policy logjam. Shutdowns are a referendum on a particular policy impasse, and they’re risky because the winner takes the spoils.