In Part 1 of “Big Man, Little Countries,” Josh Levin visits the smuggler’s paradise of Andorra. In Part 2, he surveys the fast cars and rich folks at the Monaco Grand Prix. In Part 4, he journeys to Liechtenstein for the Games of the Small States of Europe. In Part 5, he attends a tiny-country farewell party.

The day after the Monaco Grand Prix, we take a train east from the Monte Carlo station, hugging the Mediterranean coast. The water along the Côte d’Azur is a deep, postcard blue—so stereotypically, beautifully blue that I wonder if those image-obsessed Monégasques are dosing the sea with massive amounts of azure dye. After crossing into not-so-little Italy, we continue to Bologna, then (after a night of rest) on to the Adriatic resort of Rimini, 10 miles northeast of our third tiny-tour stop, the Most Serene Republic of San Marino.

In the microuniverse of little countries, San Marino is a curiosity among the curiosities. The world’s oldest republic, established in 301, is the stubborn old man of Europe, forever refusing to sell its homestead to rampaging developers. San Marino has held tightly to its independence for century after century, even as Italy unified around it and its fellow city-states vanished from the earth. It carries on today as a pebble in the Italian boot, a living fossil of old-world governance.

Like Andorra, San Marino has no extant train service, so we roll in by bus. It’s quickly apparent that San Marino’s status as a global anachronism doesn’t mean that its citizens have just discovered fire and simple tools. Rather, they partake in that staple of contemporary small-country life, duty-free commerce. Just across the border, we see bank branches, perfume shops, and an electronics superstore advertising its TAX-FREE status in huge block letters. It’s as if our old friend Andorra, unsatisfied with the volume of cologne we purchased a few days prior, has teleported over from the Pyrenees to put on the hard sell once again.

San Marino is, essentially, a 24-square-mile series of mountaintops. As we climb up to the capital, also called San Marino, the duty-free shops give way to old stone fortresses. Tour buses disgorge just outside the old city walls, and lines of Italian, German, and Russian day-trippers march up the winding, steeply sloped streets, snapping photos of the statuary and churches along the way. As the sun sets, the Italians, Germans, and Russians march back down the mountain, and San Marino’s historic center empties out. When we wander the deserted streets after dark, it feels like we’ve been locked in a theme park after closing.

There are advantages to San Marino’s Epcot feel. The lady photographer, for one, is able to acquire a cherished passport stamp at the tourist office for a fee of 5 euros. The dark side of overt tourist-friendliness is a horrific infestation of souvenirs. Every few steps, there’s another kiosk selling San Marino-specific junk (T-shirts, postcards decorated with bare-breasted women) and geographically indistinct crap (porcelain masks, an armory’s worth of toy guns). More than anything else, the country needs a tourist-trap planning commission. My first recommendation: San Marino doesn’t need both a museum of torture and a wax museum with a permanent display of ceraceous torture victims.

Despite this rampant tackiness, San Marino remains legitimately connected to its past. There are three towers on the peaks of Mount Titano, centuries-old citadels at which generations of Sammarinese stood watch for invaders. As a guidebook produced by the state tourist bureau explains, these were defensive fortifications, not “sumptuous abodes in which to cultivate mad dreams of conquest.” When you climb to the top of the first tower, it’s clear why you’d want to defend this mountaintop hideaway. In a country of scenic overlooks, this is the most scenic of them all, a panoramic view of the surrounding Italian countryside from what feels like the top of the world.

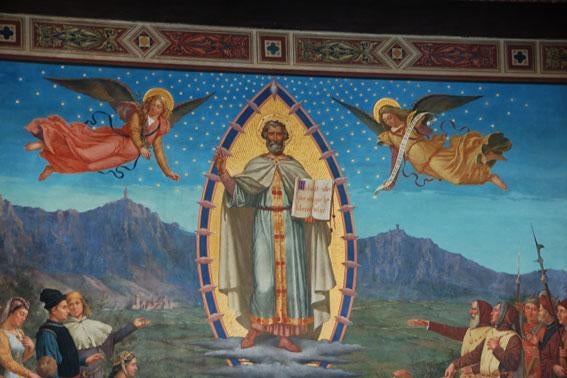

Back on terra firma, we step into San Marino’s Public Palace, opened in 1894. The palace’s Chamber of the Great and General Council, where San Marino’s legislative body confers, has me fired up to hammer out a constitution. Looming over the desks and the flat screens is an enormous tempera mural of Saint Marinus. One of history’s greatest hermits, Marinus perched on Mount Titano at the start of the fourth century and refused to leave. And that, legend has it, is how the republic was born.

Modern Sammarinese, like their patron saint, aspire to be homebodies, but the country’s economic circumstances sometimes make that impossible. In the capital, there’s an entire museum—the wonderfully curated Museo dell’Emigrante—dedicated to people who left San Marino “to be free from poverty and misery.” After various agricultural and economic crises in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, industrialization and a 1960s-era tourism boom allowed many migrants to come back home. The population in San Marino now stands at nearly 32,000, up from 15,000 in the World War II era.

The emigration museum, with all its sad tales of forced departures, points up the difference between San Marino and the other little countries we’ve visited: This place is overflowing with patriotism. The coat of arms is everywhere, and the capital is chockablock with shrines to the storied past. As in Monaco, there’s a changing of the guard ceremony outside the palace, though San Marino’s Guardia di Rocca are not as theatrically disciplined as their Monégasque counterparts. It’s a short, simple performance, one that feels less like a public presentation than an enduring national ritual. The Sammarinese, forever proud of their country, also have a charming habit of collecting compliments. After he was offered honorary citizenship in 1861, Abraham Lincoln sent a kind reply to San Marino, noting that “[a]lthough your dominion is small, your State is nevertheless one of the most honored, in all history.” A bust of Lincoln now sits inside the Public Palace, a testament to the power of a well-written thank you note.

Like the Great Emancipator, I’m getting swept up by San Marino’s cause. Those feelings swell further when we meet our local guide. Since 2007, Paolo Rondelli has served as San Marino’s first ambassador to the United States. We catch the 48-year-old Rondelli when he’s on a break from his travels—state business brings him to America three or four times a year—and he happily spends an afternoon driving us around in his Alfa Romeo. (Most Sammarinese don’t speak English—the national language is Italian—but Rondelli is fluent, having studied and worked abroad for 14 years.)

Our first stop is his mother’s home village of Montegiardino, the smallest of the country’s nine municipalities. The smallest place in San Marino is really, really small. There are around 800 residents, and the village center includes only the absolute essentials: the mayor’s office, a post office, a sports commission, and the local association of crossbowmen.

Next, we go to San Marino’s most historic graveyard. The grounds of the beautifully terraced Cimitero di Montalbo include a grave marked by a broken propeller—a memorial for a pair of Royal Air Force aviators who died in a plane crash in 1943. We also visit a consortium of local wine producers, where locals fill their jugs from self-service pumps. (Judging by the wine-colored stains on the walls and ceiling, there have been some recent accidents.)

Finally, we take a walk through a decommissioned train tunnel in the municipality of Borgo Maggiore. Benito Mussolini, who had a soft spot for San Marino—the Fascist dictator called it his Repubblica Italianissima— built a railway for the Sammarinese in the early 1930s. The railroad was destroyed by RAF bombs in 1944 and has never been rebuilt. This tunnel, remarkably, served as housing stock during World War II, when San Marino—remember, then a nation of 15,000 people—took in 100,000 refugees. It has now been turned into a cycling path, part of a nationwide network of railway relics. These are melancholy monuments: Nearby, a preserved blue-and-white train car sits atop an otherwise empty bridge, stuck in place forever.

The most remarkable thing about all these spots is that nobody else visits them. In 2008, Mount Titano and San Marino’s city center were named UNESCO world heritage sites, enshrining them as international landmarks. The rest of the country is off the map—little discussed in the country’s visitor brochures and almost entirely lacking in tourist infrastructure. (There used to be a boutique hotel in Montegiardino, Rondelli says, but it’s closed now.) Concentrating tourists in one small area ensures that the entire country won’t be choked by tchotchkes. It also guarantees that visitors don’t get to see so much of what makes San Marino special.

At the moment, the Most Serene Republic needs all the tourism money it can get. Two years ago, Italy—in desperate need of revenue during the global economic collapse—declared an amnesty for citizens who’d stashed their savings abroad as an illegal tax dodge. The plan worked as intended, to particularly disastrous effect here. Italians withdrew 5 billion euros from San Marino’s banks—about one-third of all deposits—and San Marino’s GDP fell by 13 percent in 2009. Rondelli says relations with Italy are “not as good as in the past.” San Marino’s foreign minister, less diplomatically, accused Italy of staging an “incomprehensible” economic embargo. Meanwhile, the Italians continue to treat their peninsular cohabitant as an annoying little tax cheat.

This sort of big-on-little squabble is inevitable given the economic role that small countries play. Europe’s micronations have followed in Switzerland’s footsteps, using low tax rates to draw in personal and corporate riches from beyond their borders. As you would expect, the little guys’ permissive tax laws irk their big-country brethren. San Marino’s particular geographic situation simply means it’s more likely than its little comrades to suffer for its policies.

San Marino is an only child in a single-parent household—Italy can dictate whatever terms it wants, and there’s not much anyone here can do about it. Consider the case of the country’s casino, which generated wild profits when it opened in 1949. The Italians, unhappy about the effect on Venice’s gaming proceeds, schemed to suffocate its neighbor. According to The Little Tour, the Italians instituted laborious customs checks, with everyone entering San Marino—residents and visitors, gamblers and nongamblers—being “subjected to an examination that included the removal of the wheels from their car.”

After a year and a half of harassment, San Marino gave in and closed the casino. The Sammarinese, as always, have made the best of things. The former gambling house, its marble floors still in pristine condition, now serves as a conference hall. It also stands as a testament to the fact that, for the world’s oldest republic, self-determination is a sometimes thing. After 1,700 years, San Marino remains its own country, with its own laws, flag, and stamps. The one thing it’s missing is autonomy.