Searching for Saddam

Why social network analysis hasn't led us to Osama Bin Laden.

In the immediate aftermath of Saddam Hussein's capture on Dec. 13, 2003, network theory got a brief moment of glory. The Washington Post ran a story about the role of "link diagrams" in Hussein's capture, and a handful of other articles made reference to the chart that Jim Hickey and Brian Reed had constructed.

Due to the secrecy surrounding special operations, there was no mention of Eric Maddox and his colleagues, but top military commanders took note of his contribution. Within days of returning to the United States, he met with Donald Rumsfeld, George Tenet, and a host of intelligence bigwigs. He was eventually awarded the Legion of Merit award, among others, for his contributions to the capture.

Brian Reed, too, earned notice for his contribution to the hunt for Saddam. Around the time that Reed completed his dissertation on Saddam's network, he was recruited by Gen. David Petraeus (then commanding general of Fort Leavenworth) to co-author an appendix on social-network analysis for the Army's counterinsurgency manual. (He was also invited to throw out the opening pitch at a Phillies game in his native Philadelphia, which he did on July 4, 2004.) Still, social network theory has not become a central part of the training for military intelligence officers. Most of the people interviewed said that, while there is significantly more discussion of networks now than, say, a decade ago, it's still an ancillary part of the intel toolkit.

For all Hickey, Russell, Maddox, and Reed's success in Iraq, network theory is not a silver bullet. Network diagrams helped pin down Saddam Hussein after only nine months on the run. Osama Bin Laden, meanwhile, has evaded capture for more than eight years since the United States invaded Afghanistan.

The American military's challenge in chasing Bin Laden isn't directly analogous to what it faced in Iraq. For one thing, fighting an urban insurgency requires an entirely different strategy than picking through the caves of Tora Bora and the mountainous membrane between Afghanistan and Pakistan. But there may be another reason the blueprint for tracking down Saddam doesn't easily graft onto the hunt for Bin Laden: Unlike the insurgency in the early days of the Iraq war, al-Qaida is no longer a real network.

That's the opinion of Marc Sageman, a terrorism expert and former member of the CIA who served in Afghanistan for several years. Sageman, the author of Understanding Terror Networks and Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century, argues that the still-ongoing quest for Osama Bin Laden has worked by one metric: It has effectively relegated Bin Laden to the role of a figurative leader. As the title of his second book implies, Sageman argues that al-Qaida is no longer the structured organization it was before Sept. 11. In fact, he prefers the term "blob" to "network," seeing al-Qaida and its affiliates as a loose, amorphous collection of terrorist organizations who act without central command.

Sageman is a natural skeptic who insists that counterterrorism scholarship is reliant on anecdotes rather than data. When I showed him a copy of the Saddam network, he was dismissive, saying he needed more information about how it was compiled. Under Sageman's "blob" theory, connections between players in terrorist groups evolve far too rapidly for a network diagram to keep up with. Expressing all relationships in terms of nodes and edges, he further argues, cannot account for the nuances of how people are really connected. Sageman believes social network analysis might be useful for drawing conclusions after the fact, when information about a terrorist group is more complete. He remains unconvinced of its utility as a battlefield tool.

While Sageman is one voice in a crowded field of terrorism experts, his point about the pace at which networks shift is a valid one. In Tikrit, players were captured, killed, and replaced at a low enough rate that the network was able to cohere. The churn rate is likely much higher in an extremist group like al-Qaida.

Saddam Hussein's network was also fairly rigid: The connections the dictator made throughout his decades in power were not going to disappear overnight. But unlike an insurgency based on Iraq's ancient tribal traditions, al-Qaida has the ability to shift its structure. "In its third decade, under severe pressure, [al-Qaida] has evolved into a jihadi version of an Internet-enabled direct-marketing corporation structured like Mary Kay, but with martyrdom in place of pink Cadillacs," Steve Coll wrote in TheNew Yorker in January. "Al-Qaida shifts shapes and seizes opportunities, characteristics that argue for its longevity."

In Iraq, we wanted to find the man we knew was running the country. Network analysis can be just as useful in identifying unknown sources of power. When a company or agency gets roiled by scandal, we want to know what was going on inside: Who were the ones strong-arming dissenters and punishing whistleblowers? It's not always the people with the most impressive titles who are running the show. It could very well be their underbosses, caporegimes, and commissars—the sorts of people who never find themselves under the klieg lights at a congressional hearing.

The case of Enron shows that network theory can map out a corrupt corporation just as well as an insurgency. When federal investigators released more than 500,000 e-mails between Enron employees, salivating researchers scoured the data for patterns that might have helped forecast the company's demise. Those e-mails—essentially a record of who was talking with whom—provide a far better accounting of how the company functioned than any organizational chart. Indeed, a pair of computer scientists at the Florida Institute of Technology discovered that rapid changes in the e-mail network's behavior did not coincide with external events like the resignation of the CEO. Rather, they seemed to anticipate these tectonics by roughly 30 days. Cliques—groups within the network in which every member has contact with every other member—grew eightfold in the month before the company went under. At the same time, communication became more concentrated—in other words, less CC'ing outside the clique.

The important lesson from Brian Reed's thesis is that building a network diagram is just a first step. If you really want to figure out what makes a network hum, a formal sociological analysis—down to calculating the various statistical properties of each actor—will tell you things about the network that you could not have intuited from staring at a chart. While the potential uses for social networks are truly endless, I have a couple of specific ideas about where it could work to great effect.

Mapping the presidency.

Richard Nixon's inner circle was full of sinister characters vying for influence. In the year leading up to George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq, Donald Rumsfeld, Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, and George Tenet were all trying to get the president's ear. Constructing a presidential social network would require an intimate understanding of the players inside the White House and their interpersonal relationships. In order for a network diagram to prove more insightful than your basic narrative account of the administration, you would need to map lower-level staffers for each major player, examining who has intersected with whom during their careers. This wouldn't be a simple task, but once complete you would have a nice image of how ideas travel through the administration. In network terminology, you'd be looking for "multiplexity"—cases where two people are connected in multiple ways. It would be the visual equivalent of those insider morsels that get thrown around in Washington—that so-and-so's guy on immigration plays racquetball with that senator's chief-of-staff.

Who's setting the tone of media coverage.

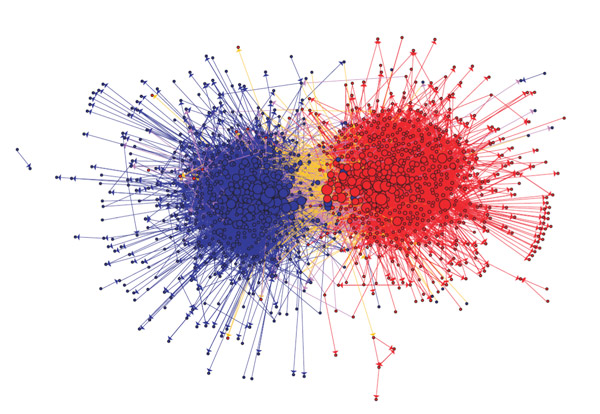

There has been lots of interesting academic research in mapping blogs as social networks. That includes one influential 2005 paper (PDF) in which the authors examined how often political blogs linked to one another. The analysis, while not heartening for post-partisans, was did produce one of the most-arresting networks I've ever seen. The diagram, which is colored by the ideology of the blog, looks like a giant red sea urchin and a giant blue sea urchin with very little connecting them.

It would be easy to construct a similar study to measure influence. A friend of mine who worked in media relations once told me that her team referred to a certain columnist as "the black sheep" because he inevitably set the pace for all other media columnists, who were just white sheep. A formal network analysis could suss out all these sheep. It might turn out, for example, that several influential reporters and bloggers all link to a relatively obscure research service or inside-the-beltway newsletter. Standard network measures—particularly betweenness centrality—could give you a clear indication of how influential each particular voice was in the overall information system.

Who should lead sports teams.

In the last decade, the sports world has seen many of its crusty truisms come under attack from statistically savvy analysts. Thinking of teams as networks could be a way for sporting sentimentalists to quantify the "intangibles" they claim are so essential to victory. For instance, coaches and managers love to talk about how hustle and leadership is contagious. They might be right, but that doesn't mean they're building their teams in a way to help that contagion spread.

In 2000, the University of Maryland's men's soccer coach Sasho Cirovski tried to do just that. As this 2006 Business Week article describes it, Cirovski's team was struggling with a lack of leadership when the coach's brother suggested that each player fill out a simple questionnaire about which teammates they consulted, who inspired them, and so forth. The social network diagram that grew out of this survey—a network of locker room leadership—had a sophomore named Scotty Buete at the center. An unassuming player, Buete indeed proved to be team leader when Cirovski trusted the network and named him a captain.

Got other ideas for how to use network theory in new, surprising, and strange ways? Please e-mail me with any and all suggestions, no matter how far-fetched. I'll go through the best ideas in a future column.

The lesson of the hunt for Saddam Hussein is that 21st-century warfare will rely just as much on sociology as technology. It's fortunate that the men on the front lines in Tikrit intrinsically understood this. As Brian Reed told me, wars are essentially fought at the brigade level and below. Saddam's capture is evidence that when the colonels and their subordinates on the ground are given the freedom to experiment with unorthodox methods, they can catch some very big fish.

To its credit, the military has made some effort to absorb the lessons of Iraq. Four years after the Iraq invasion, the Pentagon established the Human Terrain Teams program, in which social scientists have been embedded with brigades in Afghanistan and Iraq. While the concept has its supporters in the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill, its long-term future remains unclear. Some academics have lashed out against the program, arguing that it hasn't produced any empirical evidence of its utility. Others charge that it minimizes or replaces programs that would train soldiers themselves in basic sociology.

It does indeed seem shortsighted to contract out the sociology of warfare to a few men and women among thousands of soldiers. It has to become a priority for those in the military's highest ranks, something that's not yet the case.

It's possible that network theory hasn't caught on for cultural reasons. David Segal, a military sociologist at the University of Maryland, says that it's hard to convince young officers of the importance of family networks in Iraq and elsewhere when Americans aren't nearly as connected to their extended families as they used to be. We don't think of our family, friends, neighbors, church mates, or drinking buddies as the potential backbone of an insurgency. That's precisely what happened in Iraq, however—when Saddam Hussein needed protection, he looked to his extended family and existing social institutions.

For network theory to become ingrained in the American military, it will simply need to keep proving itself. There have already been more success stories. Maddox, who has been sent on many missions to combat zones, says link diagrams were integral to the 2005 capture of Muhammad Khalaf Shakar, a high ranking al-Qaida operative in Iraq also known as Abu Talba. The manhunt, which Maddox was able to tell me about in general terms, relied on techniques similar to the network manipulations described in the third part of this series. As in the case of Saddam, soldiers mapped out Shakar's close associates and worked their way to the center of the network. They had their prey in a matter of weeks.

Become a fan of Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.