Slate’s archives are full of fascinating stories. We’re republishing this article on Easter weekend because it remains a reader favorite. It was originally published April 9, 2009.

A central statement in traditional Christian creeds is that Jesus was crucified “under Pontius Pilate.” But the majority of Christians have only the vaguest sense what the phrase represents, and most non-Christians probably can’t imagine why it’s such an integral part of Christian faith. “Crucified under Pontius Pilate” provides the Jesus story with its most obvious link to larger human history. Pilate was a historical figure, the Roman procurator of Judea; he was referred to in other sources of the time and even mentioned in an inscription found at the site of ancient Caesarea in Israel. Linking Jesus’ death with Pilate represents the insistence that Jesus was a real person, not merely a figure of myth or legend. More than this, the phrase also communicates concisely some pretty important specifics of that historical event.

For one thing, the statement asserts that Jesus didn’t simply die; he was killed. This was a young man’s death in pain and public humiliation, not a peaceful end to a long life. Also, this wasn’t a mob action. Jesus is said to have been executed, not lynched, and by the duly appointed governmental authority of Roman Judea. There was a hearing of some sort, and the official responsible for civil order and Roman peace and justice condemned Jesus. This means that Pilate found something so serious as to warrant the death penalty.

But this was also a particular kind of death penalty. The Romans had an assortment of means by which to carry out a judicial execution; some, such as beheading, were quicker and less painful than crucifixion. Death by crucifixion was reserved for particular crimes and particular classes. Those with proper Roman citizenship were supposed to be immune from crucifixion, although they might be executed by other means. Crucifixion was commonly regarded as not only frighteningly painful but also the most shameful of deaths. Essentially, it was reserved for those who were perceived as raising their hands against Roman rule or those who in some other way seemed to challenge the social order—for example, slaves who attacked their masters, and insurrectionists, such as the many Jews crucified by Roman Gen. Vespasian in the Jewish rebellion of 66-72.

So the most likely crime for which Jesus was crucified is reflected in the Gospels’ account of the charge attached to Jesus’ cross: “King of the Jews.” That is, either Jesus himself claimed to be the Jewish royal messiah, or his followers put out this claim. That would do to get yourself crucified by the Romans.

Indeed, one criterion that ought to be applied more rigorously in modern scholarly proposals about the “historical Jesus” is what we might call the condition of “crucifiability”: You ought to produce a picture of Jesus that accounts for him being crucified. Urging people to be kind to one another, or advocating a more flexible interpretation of Jewish law, or even condemning the Temple and its leadership—none of these crimes is likely to have led to crucifixion. For example, first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus tells of a man who prophesied against the Temple. Instead of condemning him, the governor decided that he was harmless, although somewhat deranged and annoying to the Temple priests. So, after being flogged, he was released.

The royal-messiah claim would also help explain why Jesus was executed but his followers were not. This wasn’t a cell of plotters. Jesus himself was the issue. Furthermore, Pilate took some serious flak for being a bit too violent in his response to Jews and Samaritans who simply demonstrated vigorously against his policies. Pilate probably decided that publicly executing Jesus would snuff out the messianic enthusiasm of his followers without racking up more Jewish bodies than necessary.

Of course, the Gospels also implicate Jewish religious authorities—specifically, the priestly leaders who managed the Jerusalem Temple under franchise from the Roman government. Many scholars, including E.P. Sanders in Jesus and Judaism, conclude that the Temple leaders were likely involved in Jesus coming to the attention of Pilate. After all, the high priest and his retinue held their posts by demonstrating continuing loyalty to Rome. If they judged that Jesus represented some threat to Roman rule, they were obliged to denounce him. Also, it is not so difficult to grant a certain likelihood to the Gospels’ claim that the Temple authorities were at least partly motivated by a resentment of Jesus’ criticism of their administration of the Temple, as may be reflected in the account of Jesus overturning the tables of the money-changers who operated in the premises under license from the high priest. But Jewish leaders didn’t crucify Jesus. “Crucified under Pontius Pilate” points to where that responsibility lies, with the Roman administration.

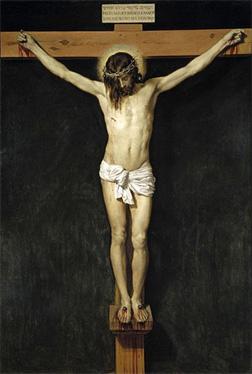

It’s rather clear what St. Paul meant by saying that “the preaching of the cross is foolishness” to most people of his day. As Martin Hengel showed in Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross,Roman-era writers deemed crucifixion the worst imaginable fate, a punishment of unspeakable shamefulness. Celsus, a Roman critic of Christianity, ridiculed Christians for treating as divine someone who had been crucified. A second-century anti-Christian graffito from Rome, well-known among historians who study the time period, depicts a crudely drawn crucified man with a donkey’s head; under it stands a human figure, and beneath this is a derisive scrawl: “Alexamenos worships his god.”

There was, in short, little to be gained in proclaiming a crucified saviour in that setting in which crucifixion was a grisly reality. Some early Christians tried to avoid reference to Jesus’ crucifixion, while others preferred one or another alternate scenario. In one version, in a Christian apocryphal text, the soldiers confuse a bystander with Jesus, crucifying him instead, while Jesus is pictured as laughing at their folly. This idea is likely also reflected later in the Muslim tradition that a person from the crowd was mistakenly crucified as Jesus escaped. Many devout Muslims believe that Jesus was a true prophet, so it is simply inconceivable that God would have allowed him to die such a shameful death. Clearly, at least some early Christians felt the same way.

In fact, Jesus’ crucifixion posed a whole clutch of potential problems for early Christians. It meant that at the origin and heart of their faith was a state execution and that their revered savior had been tried and found guilty by the representative of Roman imperial authority. This likely made a good many people wonder if the Christians weren’t some seriously subversive movement. It was, at least, not the sort of group that readily appealed to those who cared about their social standing.

Jesus’ crucifixion represented a collision between Jesus and Roman governmental authority, an obvious liability to early Christian efforts to promote their faith. Yet, remarkably, they somehow succeeded. Centuries of subsequent Christian tradition have made the image of the crucified Jesus so familiar that the offensiveness of the event that it portrays has been almost completely lost.