On April 29, 1969, Carnegie Hall was sold out. The artist who filled the fabled performance hall wasn’t a symphony orchestra, or a Broadway belter, or a jazz star. It wasn’t a rock band or a folk singer or any hero of the counterculture taking the stage just a few months before Woodstock. On that night, more than 3,000 fans filled the Main Hall on 57th Street to see a placid blond man wearing a sweatshirt and sneakers. He stood before a microphone on his 36th birthday and performed a poem about a lost cat named Sloopy.

But once upon a time

In New York’s jungle, in a tree

Before I went into the world in search of other kinds of love

Nobody owned me but a cat named Sloopy.

His name was Rod McKuen. He was the most popular poet in American publishing history.

Rod McKuen sold millions of poetry books in the 1960s and 1970s. He was a regular on late-night TV. He released dozens of albums, wrote songs for Sinatra, and was nominated for two Oscars. He was a flashpoint in the battle between highbrow and lowbrow, with devotees revering his plain-spoken honesty and Dick Cavett mockingly calling him “the most understood poet in America.” Every year on his birthday, he sold out Carnegie Hall.

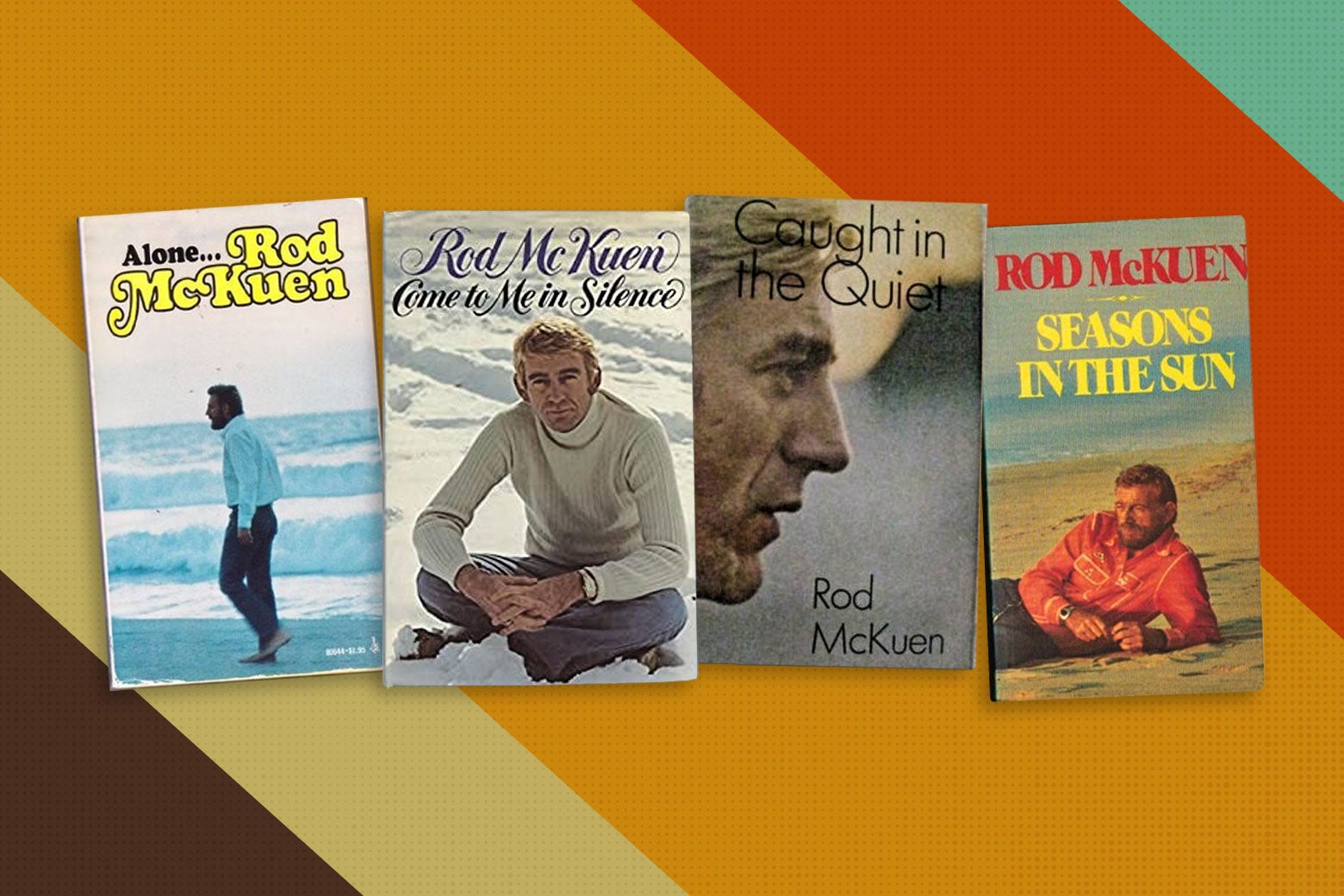

But by the time I was a teenager, he had completely vanished from the cultural landscape. I only know of him because I spent the entire 1990s in thrift stores and used bookshops, and everywhere I went, I saw Rod McKuen’s name. His chiseled face stared out at me from abandoned hardcovers, torn paperbacks, and dusty record albums, all adorned with the most ’70s fonts you ever saw. He wore a turtleneck and luxurious blond hair on the cover of Come to Me in Silence. He reclined on a sandy beach on the front of Seasons in the Sun. On one paperback he stared out to sea and the title of the book told me just how he felt: Alone…

I wanted to know who this incredibly famous poet was, and who his fans were, and how he was forgotten. I went searching for Rod McKuen, and I found a young man so hungry for fame that he wrote his own fan letters, a singer of novelty tunes whose early hit got plagiarized into a punk anthem, a gay celebrity who winked about his sexuality but had to lie about the man he loved. I learned that it takes a lot of dedication and hard work and luck to attain fame, but it takes something more than that to retain it. And along the way I met a man who, like me, was bewildered by this forgotten star—until he became an accidental fan, and then even more accidentally became the only person keeping Rod McKuen’s flame alive.

Listen to another version of this story on Slate’s Decoder Ring:

Rod McKuen was a born liar. Let’s say: a storyteller. “It made my job very, very hard,” said Barry Alfonso, the author of the only serious biography of Rod McKuen, called A Voice of the Warm. “He was a fabulator,” Alfonso told me. “He made up lots of stuff about himself.” McKuen claimed he was employed as a cowboy as a preteen. He claimed he made movies in Japan no one has ever seen. He even claimed he had two children, which he did not.

What drove his predilection for self-invention? “Having a terrible childhood and a sense of inferiority,” Alfonso said. “A sense of never being legitimate.”

Rod McKuen’s mother was unmarried when she gave birth to him, in a charity hospital in Oakland, California, in 1933. McKuen would never know who his father was. When he was little, his mom left him with her sister for months while she worked in San Francisco as a taxi dancer, charging men a dime a dance in nightclubs. When she returned, she took him to Nevada, where she’d married a violent, hard-drinking man who abused McKuen physically and sexually. The family bounced from town to town. McKuen became a chronic runaway and a street hustler. Eventually, he was sent to a brutal reform school.

By the time he was a teenager, he was desperate to get famous. If he couldn’t get love, respect, and validation from his family, he was going to get it from everybody else. He got his first shot before he even turned 20, when he got a job as a DJ on Oakland’s KROW radio station, doing a show called Rendezvous With Rod. It took him a while to figure out the right formula. He started out doing zany comedy sketches. Then he tried spinning popular records. But one day, KROW listeners tuned in and heard a young man murmuring sweet nothings into the microphone. “Last night I felt a sharp pain of loneliness,” went a typical episode of Rendezvous. “Tonight, with you here, the loneliness is gone.”

Though he would try on a lot of other personalities over the years, this was the first sign of the McKuen who would eventually become famous: lonesome, aching, romantic. A poet, of sorts. This persona turned Rendezvous With Rod into a hit. But while he was pitching woo to teenage girls over the airwaves, he was also embracing a different identity in his private life.

In the spring of 1953, the San Francisco branch of an early gay rights organization had its first meetings. In the minutes for the Mattachine Society’s April meeting, most of the participants are anonymous, but one name appears over and over: Rod McKuen.

He was only 19, at a time when to be gay was to be considered a sex offender, a Communist, or both. He was just starting his radio show, just trying to be famous. But there he was, urging members to lobby candidates yet also suggesting the society rent a theater and throw a big party. “Everyone agrees Mattachine meetings are wonderful places for cruising,” he said. “Better than bars.”

McKuen’s connection to the society ended when he was drafted into the Korean War in 1953. He spent two years in Korea working on radio propaganda. While there, he later claimed, he coined the phrase “make love, not war” as a way of persuading North Korean soldiers to return to their girlfriends at home. There’s no evidence this is true, says Barry Alfonso.

Upon his return to the U.S. in 1955, he pulled out all the stops. He was going to become famous, and he didn’t particularly care how—or where—it happened. In San Francisco, he sang and read his poems at the famous Purple Onion in San Francisco, where he shared the stage with comedian Phyllis Diller and poet Maya Angelou, who in those days was singing and dancing calypso. One folkie of the era remembers that McKuen carried around a press kit filled with fake photos of him with celebrities like Harry Belafonte.

In Los Angeles, he tried to make it in the movies, playing characters with names like “Ox Bentley” in forgettable teen flicks. But Universal never gave him a lead role, despite the fact that he and his manager wrote fake fan letters from teenagers and mailed them to the studio every day. In New York, McKuen somehow got a job writing incidental music for CBS, even though he couldn’t read music or play an instrument.

And McKuen started making records. Folk records, romantic records, instrumental records—anything he thought might be a hit. He tried novelty songs, like an extremely mild satire of beatniks called “The Beat Generation.” He leapt on every bandwagon that rolled by: In 1961, just a year after Chubby Checker first hit No. 1 with “The Twist,” McKuen released “Oliver Twist,” an under-two-minute absurdity that peaked at No. 76. McKuen toured on that near-success, howling over the ambiance at bowling alleys and bars, doing permanent damage to his vocal cords, he later said—hence his distinctive rasp in later years.

In the mid-1960s McKuen discovered the Belgian singer Jacques Brel and his fellow chansonniers, performers in the story-song tradition who were popular in the cabarets of Europe but hadn’t yet made inroads in the U.S. market. McKuen translated and sang a number of Brel’s songs, and fully rewrote Brel’s song “Le Moribond” as “Seasons in the Sun,” which was recorded by the Kingston Trio. (It would later be a No. 1 hit for the singer Terry Jacks.)

McKuen sang his American chansons in cabarets all over the country, selling his self-published poetry books out of the trunk of his car. He wasn’t scoring hits, but he was drawing crowds, and he was getting the best notices of his career. A 1965 New York Times review of his show at the Bitter End called him “intensely effective at vocal mood-building.” McKuen wasn’t a natural Beat or a natural rocker or a natural joker. But he was a natural at this world-weary, sophisticated, misty-eyed vibe.

As it turned out, McKuen’s first gigantic hit record, in 1967, didn’t feature his singing. It didn’t even feature his voice. It did, however, bring his poetry into living rooms across the country. It was called The Sea.

Over a lush bed of strings, and the sound of ocean waves, a voice intones sweet nothings. “Perhaps the time will come when I no longer smile the way I did this morning,” the voice says. “Maybe the sea will say of us, ‘They loved one Sunday.’ ” The Sea was a collaboration between McKuen and the composer and arranger Anita Kerr. For contractual reasons, McKuen couldn’t even appear on the album, so his gentle come-ons were read by the actor Jesse Pearson, best known from Bye Bye Birdie. The album was credited to an ensemble that Kerr and McKuen invented, called the San Sebastian Strings. And in the 1960s, it was the soundtrack to innumerable romantic assignations.

“If you’re between 45 and 55, there’s a pretty good chance you were conceived to this album,” said Andy Zax, a music historian and archival producer. “It was a make-out record, for lack of a better term. I’m not sure that really does it justice, but that does explain some of its popularity, which was immense.” The album sold and sold, to ambitious bachelors and young couples, to leches and romantics both. It remained on the Billboard album charts for 143 weeks. Even years after its release, it continued to sell: According to Zax, until Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 Rumours became a perennial, The Sea was the best-selling album in the Warner Bros. back catalog.

The same year, McKuen finally signed a deal to do the thing that would really make him famous: poetry. Legendary editor Nan Talese, then at the beginning of her career, paid McKuen a $750 advance to publish a new book of poems. Listen to the Warm included a number of the poems from The Sea. It also included “A Cat Named Sloopy,” which would become McKuen’s signature work.

“Sloopy” is sentimental but has, for its time, a keen edge of sexual adventure. McKuen tells of the “dozen summers” when the cat was his companion in an apartment on 55th Street in New York. While McKuen goes off on dalliances with “Ben” and “Lillian,” Sloopy waits patiently among the avocado plants on the windowsill for McKuen to return with “arms full of canned liver and love.” But one winter McKuen stays away too long and when he returns, Sloopy is gone. He searches for the cat, screaming her name as he tromps through the snow. “Looking back,” the poem ends, mournfully, “perhaps she’s been/ the only human thing /that ever gave back love to me.”

Before there were internet-viral poems, “Sloopy” was a viral poem. Passed by word of mouth from friend to friend, lover to lover, cat person to cat person, the poem served as a ticket into McKuen’s world of longing, love, and loss. When RCA released the album version of Listen to the Warm three months after the book, it led off with “A Cat Named Sloopy” and ended, 36 minutes later, with McKuen plaintively groaning Sloopy’s name over a sugar-sweet string ensemble. It was not even a little bit cool. But it was a hit.

Random House hustled to acquire the book McKuen had been selling out of his trunk, Stanyan Street and Other Sorrows. This time, they had to pay him $10,000. It was worth it. By 1970, McKuen titles made up 4 percent of Random House’s total sales volume.

This is not the way poetry sells now, and it wasn’t the way poetry sold then. Poetry held a slightly more exalted place in the culture in the 1960s, but it was never a huge moneymaker. Sometimes poets for children, like Shel Silverstein, got big. But serious poets printed by adult publishers, even cultural heroes, didn’t sell like Rod McKuen. Take Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, the most famous of the Beat poems. That book took nearly 50 years to sell a million copies. McKuen sold a million in his first year at Random House alone.

Thus began the incredible peak of Rod McKuen’s fame. “From about 1969 through ’72 or so, Rod McKuen was just literally unavoidable,” said Barry Alfonso. Each year McKuen published two or three books and released as many as 10 albums. He was profiled in Life, McCall’s, the New York Times Magazine. He won a Grammy for Best Spoken Word Recording, got an Oscar nomination for a song from the Maggie Smith movie The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, and got another for the music he wrote for a Peanuts film. Artists from Perry Como to Dusty Springfield sang his songs. Frank Sinatra, desperate to connect to a younger audience, recorded a whole album of McKuen tracks. And if you turned on a TV, there he was. Game show contestant, panel personality, and talk-show guest par excellence.

It’s hard to characterize McKuen’s fame, with its mix of books, music, and TV, in a contemporary context. “It would have been some combination of Rupi Kaur, Jimmy Kimmel, and Ed Sheeran,” said Stephanie Burt, a poet and critic who teaches at Harvard. “He was really that level of everyone knows who this person is.”

And in addition to all the records, the books, the tours, the TV appearances, he was also launching his own business. Stanyan Records was formed to release all of McKuen’s albums, but it soon diversified into a hugely successful catalog business. McKuen convinced labels to grant him the rights to a bunch of old music that wasn’t cool anymore, the music of his youth and lots of other people’s youth, and he released it on Stanyan: Judy Garland, Sylvia Syms, Vera Lynn. “Major labels had absolutely no imperative at this period of time to put out Vera Lynn records,” said Zax. “And so this ended up being really shrewd counterprogramming.” Andy Zax estimates that Stanyan released at least 25 records that would have been certified gold had McKuen ever bothered to join the RIAA. Stanyan products had a built-in audience, after all. “If you went to see Rod McKuen live in concert any time in the early ’70s,” said Zax, “there was a postcard sitting on your chair: ‘Get on the Stanyan Records mailing list.’ ”

Stanyan also became the home for Rod McKuen merch. McKuen jackets, bags, calendars, notepads, little books of aphorisms. He made a deal for Rod McKuen–branded tulips you could send to your loved one, and issued little 45s you could mail to friends with messages that I’m sure seemed very sensitive at the time, like this one:

I get off on you.

Really.

I don’t know if it has to do with age or getting older or what.

But for a while I thought I was never going to find anybody who was tuned in on the same wavelength as me.

Or maybe somebody I could tune in with.

It sure feels good.

“Please try not to over-extend your energy,” McKuen’s editor Nan Talese urged him in a letter. “I’m not asking you to be less ambitious. I am only asking you not to spread yourself too thin.” At the peak of his fame, McKuen ignored this advice. “He left no stone unturned,” Zax said admiringly. He pointed out that there are real similarities between Stanyan’s business model and that of, say, legendary DIY label Dischord in the 1980s. “You know, the Rod McKuen–Minor Threat connection is previously untheorized,” Zax joked, “but it’s nonetheless valid.”

I couldn’t help but wonder, surveying the flood of product McKuen produced: Who was all this stuff for? Who were the people who loved Rod McKuen?

Rod McKuen’s whole deal does not exactly fit into my sense of the tumultuous late ’60s and early ’70s. And yet, McKuen was there, as big a star in his own world as Bob Dylan was in his—and, in his way, as much a part of the zeitgeist.

“There was this great longing for closeness and connection that people of all different backgrounds felt at that time,” said Alfonso. “They didn’t want to go out and smoke pot and get naked at the love-in, but they wanted to feel like they could get beyond this sort of stultified way of men and women, and people in general, relating to one another.” In 1969, there were about 40 million Americans between 15 and 30. Yes, 400,000 of them went to Woodstock. What about all the rest? Well, a lot of them were Rod McKuen fans.

Bill McCloud is a retired public schoolteacher and an adjunct professor in Tulsa. But in 1966, he was a 17-year-old who’d just landed an on-air job at WBBZ in Ponca City, Oklahoma. That’s where he fell for Rod McKuen.

“As a teenage boy, I felt sad about lots of things,” McCloud told me. “Life seemed to be sad. And by George, Rod McKuen was sad too, and we could be sad together.” McKuen’s songs led him to McKuen’s poems, which McCloud loved because they were so approachable, “conversational,” he said. “He doesn’t start each line with a capital letter. His poems are like he’s talking to you.” He loves them all, but he’s got a special place in his heart for “Sloopy”: “Even if that was the only poem Rod McKuen had ever written, he would be one of my all-time favorite poets.”

“Sloopy” was how Mari LaFore discovered McKuen’s work, in 1970, when a boyfriend played the recorded version for her and took her to a concert in Madison, Wisconsin. LaFore still lives in Madison, and still considers herself a fan. Like McCloud, she marvels at how clearly McKuen expresses emotions and how much she relates to all that he writes about. “He just pulls out of you the unsaid things and the thoughts, the feelings,” she said. “And you’re like, Yes, that’s how I feel.”

“McKuen, writing in the 1960s, has poetry that’s overwhelmingly feeling-oriented,” explained Mike Chasar, a professor of English at Willamette University, where he studies the intersection of poetry and pop culture. “He is not afraid to name and write about sorrow or grief or love or excitement or loss or fear.” In the ’60s, Chasar continued, “he offered a different model of masculinity to people, about how they could feel the world in ways that weren’t necessarily publicly available.”

That ability to express emotions that might otherwise go unsaid seems key to a phenomenon several people I interviewed noticed: that lots of their old Rod McKuen books sport handwritten inscriptions in the front. Think of them as the mixtapes of their day, said Erik Noftle, also a professor at Willamette: “They were given, you know, to men, to help them understand the internal world of feeling, or they were given to women to acknowledge that world.”

Inside my copy of Stanyan Street and Other Sorrows, purchased from a used bookstore in Reno, Nevada, there’s this inscription in neat cursive:

Lane: Here’s a beautiful book for a beautiful person. McKuen’s a cool guy who knows how to really express himself and I think you’re one person who can understand what he’s trying to say. Stay cool, kiddo! Love, Nanc.

Sometimes the connections McKuen’s work forged were within families. Bill McCloud mentioned that growing up he was only the second-biggest McKuen fan in his house; his mom was No. 1. And Mari LaFore told me about her second Rod McKuen concert, in 2001. She brought her daughter, and Mari later wrote her own poem about the experience. In the poem, they line up to get McKuen’s autograph after the show, and her daughter tells McKuen, “I grew up listening to your poetry. You always talked about love, and I’ve never forgotten that.” The poem is called “I Thought She Wasn’t Listening.” Reading it to me, LaFore burst into tears.

But Rod McKuen was also a joke.

In 1968, Karl Shapiro, a former poet laureate of the U.S., wrote: “It is irrelevant to speak of McKuen as a poet. His poetry is not even trash.” A 1969 L.A. Times review said, “One can find better verse on the walls of restrooms.” His success, the critic added, “is an incredible indictment of the poor taste and cultural deprivation of the American public.”

What did critics hate about McKuen? Well, part of the problem, for these highbrow critics, was that he was, as Margot Hentoff put it in the New York Review of Books, “all too accessible.” That made it easy to scorn you, the fan, as the type of rube who has to, as one particularly cruel piece in the New Republic put it, “move your lips rapidly as you read.”

Even the critics who weren’t quite so overtly snobby clearly disdained McKuen’s fans for the crime of merely being ordinary. Hentoff witheringly describes the crowd at Carnegie Hall as “contingents of thirtyish women who might have come from the airline offices, the telephone company, innumerable typing pools.” Future Hollywood writer Nora Ephron wrote a McKuen takedown in Esquire, called “Mush,” that observes the audience at a D.C. show: “You won’t see any of your freaks here, no sir, any of your tie-dye people, any of your long-haired kids in jeans lighting joints. This is middle America.” When Nora Ephron calls you middlebrow: sheesh!

And when a lot of rubes like your poetry, you get rich. By 1970, McKuen had bought a 30-bedroom mansion in Beverly Hills. “Poetry is not supposed to be a moneymaking endeavor,” said Willamette’s Mike Chasar, describing the view among the gatekeepers of poetry, then and now. “The fact that you’re not making money somehow signifies the purity of your art, your refusal to capitulate to the capitalism of the 20th century, which has corrupted other art forms. Poetry is a sort of last holdout against that, and someone who’s profiting off of it seems to be, you know, betraying the tribe.” That same New Republic piece made clear just how insincere critics thought McKuen was. Louis Coxe wrote, “McKuen is no dope and knows what he is doing, i.e., weeping nostalgically all the way to the bank.”

At first, McKuen brushed the critics off. “I never really call it poetry, myself,” he said in 1968. But as the reviews got harsher, and he got richer, he started to bristle. “There are a lot of people who take potshots at me because they feel I’m not writing like Keats or Eliot,” he said in 1971. “And yet I’ve been compared to both of them. So figure that out.”

The disdain directed at McKuen and his fans makes me want to defend him from a bunch of gatekeeping snobs—and there are ways to do that. Chasar talks about McKuen’s poetry in the lineage of the Beats, who so prized authenticity; of the confessional poets of the 1960s, including Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell; and especially of one of McKuen’s heroes, Walt Whitman. McKuen released two albums of musical accompaniment to Whitman poems. “Whitman, too, had sequences of love poems that, by today’s ears, sometimes sound schmaltzy,” said Chasar. “But Whitman never shied away from being a poet of feeling, either.”

One contemporary poet whose career McKuen calls to mind is Rupi Kaur, the Canadian “Instapoet” whose sales, since her self-published debut in 2014, have rivalled McKuen’s at his peak. While both Chasar and Stephanie Burt noted that while there are specifics to the two poets’ backgrounds and careers that make them hesitant to compare their work one on one, they see similarities. Chasar pointed to the way that Kaur, too, cultivates a sense of authenticity, while Burt noted that Kaur, like McKuen, is not only writing poetry; she’s “selling a particular image of a poet.”

As McKuen did, Kaur writes poems that are instantly accessible to readers who might not have previously consumed much poetry. (Hers are generally lowercase, short, and made to fit in an Instagram frame.) Unlike McKuen, though, her work has mostly been given a pass by mainstream publications, which in the poptimistic 21st century are much less likely to savage a megasuccessful artist and her fans. Yes, there’s the occasional harsh critique (often very astute) in smaller journals—and plenty of satire on Twitter, long the devil to Instagram’s angel. And the Cut published, in 2017, a deliciously arch profile. But the New York Times, to choose one example, has treated Kaur very gently: “like a cross between Charles Bukowski and Cat Power,” noted the Book Review. “Ms. Kaur’s work reminds us that the ordinary business and experience of millennial minority women is not to be dismissed,” wrote Tariro Mzezewa in the same newspaper. Slate’s own Carl Wilson, though admitting “the Instapoets don’t do much for me aesthetically,” forcefully made the case in the Times that “my tastes aren’t the point here”—his being the tastes of “a 20th-century leftover.” “It won’t hurt poetry,” he wrote, “if for a few years a coterie of readers find their thoughts and feelings reflected back at them in verse form.”

And here’s where I reveal myself to be a snob. I have a hard time bringing myself to be that open-minded. I really think a lot of Rod McKuen’s poetry stinks. It’s not just that the poems are dull, or schmaltzy. I find them actively embarrassing.

Now I have the time for football all fall long

and to apologize for little lies

and to apologize for little lies

told when there was no time to explain the truth

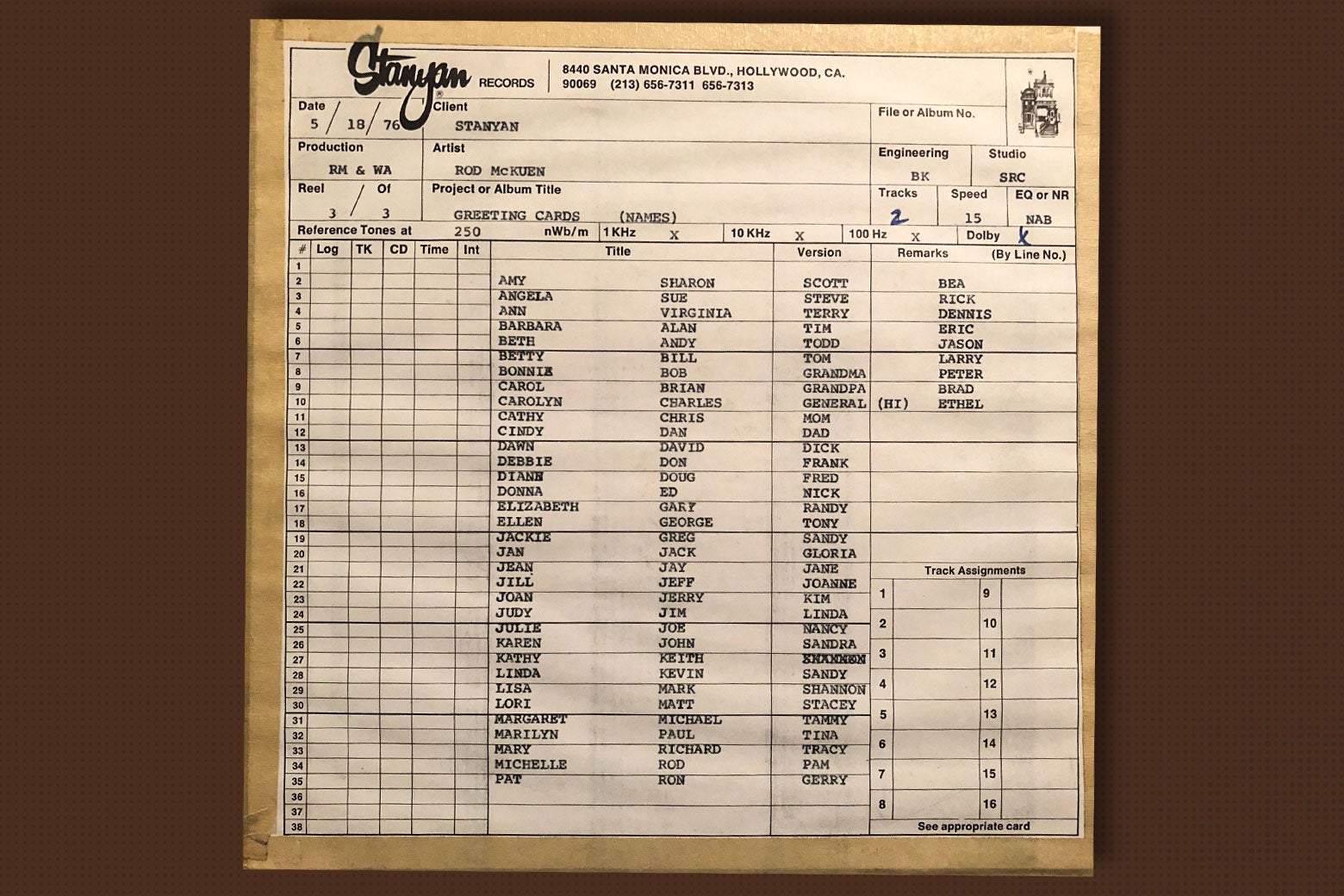

There’s something about bad poetry that’s perhaps more painful than any other bad art. It’s so open and yet so empty. It reveals the yawning banality at the center of all our souls. I read McKuen’s poems and I think, Ugh, that’s a B-minus Hallmark Card. And, in fact, in the mid-1970s, McKuen actually signed a deal with Hallmark. It was for a series of greeting cards that included semipersonalized recordings for the 150 most common first names of the time. I’ve got the tape from his recording session. “Hi Stacey. Thank you, Stacey. Thank you for being you,” he says. “Hi Tammy. Thank you, Tammy. Thank you for being you.” And so on.

Perhaps it seems cruel to dig up this forgotten poet who is only remembered by people who love him. Especially because, unlike his critics at the time, I don’t think McKuen was insincere. At least not at first. It’s not an accident that this was the stuff that made him famous, not novelty songs or movie acting. He meant it, and people could feel that. “I think he was tapping into a real longing and a real loneliness that he had, and finding a way to market it,” Barry Alfonso told me. The trouble came as he kept having to perform longing and loneliness over and over. Alfonso put it best: “How often can you market your sincerity before it isn’t sincere anymore?”

Through the 1970s, as McKuen was walking this fine line—of being beloved, productive and yet also totally disparaged—he was walking another fine line. His poems and songs alluded to cruising, to trysts with countless lovers, male, female, and carefully gender-nonspecific. He wrote about his days as a teenage hustler. But he never, ever said he was gay.

“Of course he wasn’t out,” said Stephanie Burt. In that era, she said, a queer person who wanted to become, and stay, famous, had three choices. “You could be studiously asexual and try to be famous for something else, so that people just wouldn’t think about who you slept with. You could be really just flaming, out there, and obviously super gay. You could be Liberace. And that the third way, which is the way that that McKuen seems to have chosen, was to be soft-focus, small-R romantic and carefully nonspecific.”

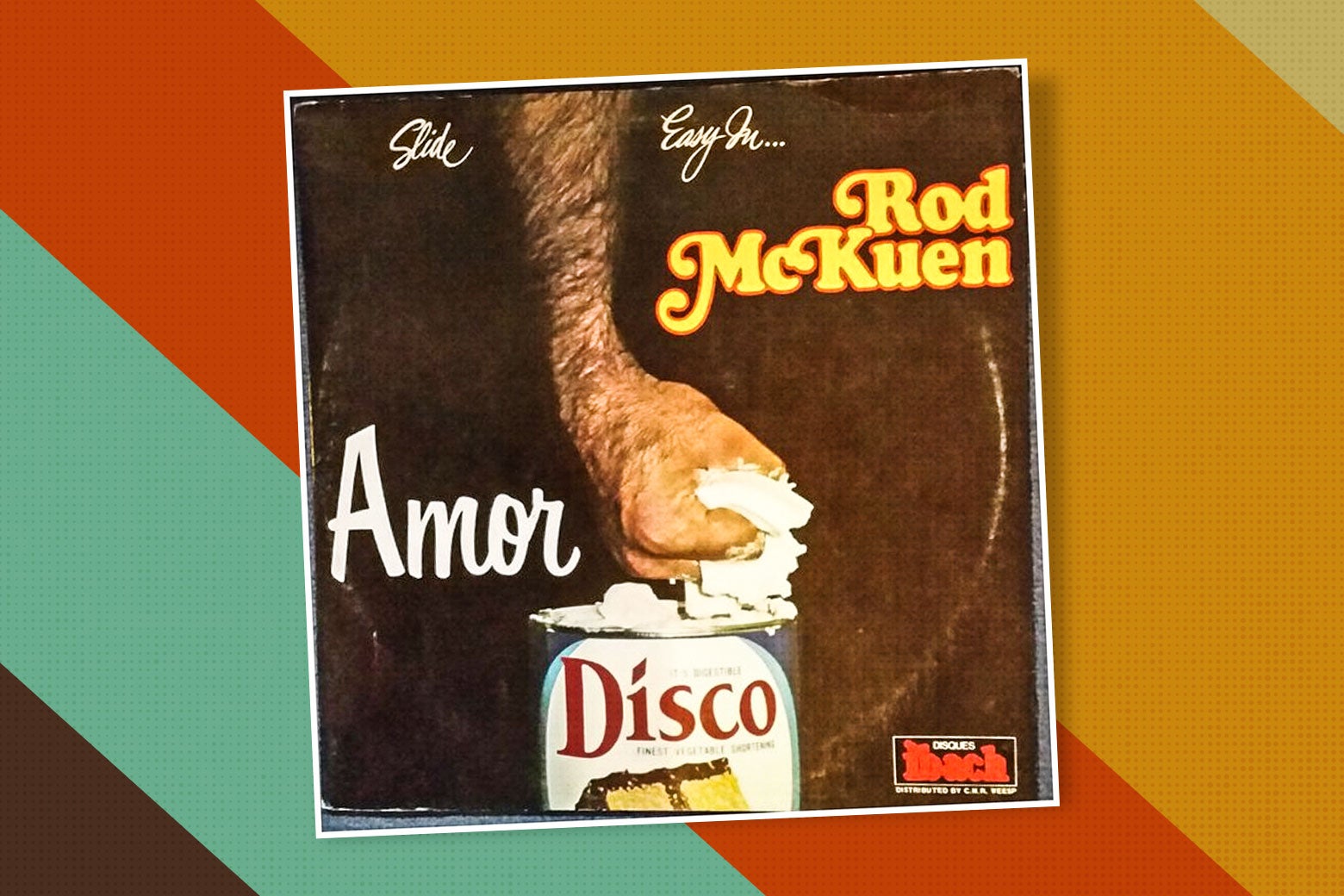

Barry Alfonso describes McKuen’s public treatment of his sexuality as “personally discreet but strategically provocative.” If you knew what you were looking for, if you were a specific segment of McKuen’s audience, it was there. All those Judy Garland reissues on Stanyan Records. The disco album McKuen released featuring a porn star’s Crisco-slathered fist on the cover.

In 1977, McKuen campaigned against Anita Bryant’s anti-gay laws in Florida. It was the only real political activism he ever engaged in. When a spokesman for Bryant’s Save Our Children lumped McKuen in with all the other “perverts,” McKuen said he’d give him $100,000 if he could prove he was a homosexual. McKuen said, “I’ve been attracted to men and I’ve been attracted to women. I have a 16-year-old son. You put a label on me.”

This is a bold response for sure, and I love it. But I’d also note that, in classic Rod McKuen fashion, there was no son. As far as Barry Alfonso could find, all of his close relationships with women were platonic. He claimed for decades he had illegitimate children in France, but nope, he never did.

He did have a life partner, though, a man he loved and lived with for decades. His name was Edward Habib. McKuen met him in the late 1950s, and they lived together right up until Rod’s death. “Rod, at various points in his career, asserted that Ed was his photographer, his manager, his biographer,” Alfonso said, none of which were strictly true. At one point McKuen simply told everyone that Ed was his brother.

Rod McKuen told the world it didn’t matter whom you loved. He told the world you should be open, earnest, with your feelings—put it all out there. He fostered connection, a way for people to tell others what they couldn’t say themselves. But he lived in a world where he couldn’t put it all out there, he couldn’t say everything.

This brings me back to some of what he did say—all of his fibs. Barry Alfonso told me that despite everything, he ended up feeling forgiving toward Rod, because “it seemed like he didn’t harm anyone” with his “white lies.” And maybe he’s right. Maybe it’s harmless, even kind of charmingly brazen, to say you invented the phrase “make love, not war” or “midnight cowboy”—another one McKuen claimed was his. Or to write your own fan letters. But when you’re telling people you have illegitimate children, and meanwhile the man you love is standing next to you pretending to be your brother—you don’t seem so unharmed yourself.

In the 1970s Rod McKuen did more work than many people do in a lifetime. His will to succeed, his drive to fame, seemed insatiable. But as the ’70s came to an end, McKuen would start to disappear.

AIDS was devastating a generation of gay men. His longtime friend Rock Hudson died of the disease in 1985. The total romantic and erotic freedom McKuen had written about in the 1960s and ’70s, was over, abruptly, terrifyingly. McKuen was becoming seriously depressed. “I never left the yard for two years,” he said. “I didn’t answer the phone.”

Outside the yard, the culture was changing. This kind of soft, sensual horniness was no longer in vogue. For many people, Rod McKuen became someone you were embarrassed you ever loved when you were young. And all those books with the dedications in them from a girl who eventually dumped you because you never quite figured out how to get in touch with your emotions, they go straight to Goodwill.

Meanwhile, the pipeline for new Rod McKuen product slowed to a trickle. Andy Zax, the music historian, said he suspects McKuen must have imagined that, depression or no, the money was just going to keep rolling in. And so McKuen let a lot of opportunities slide. As he said, he didn’t answer the phone. Licensing deals expired. He lost track of all of the royalties he was due from other artists covering his songs, or of the payments coming in from Europe, Asia, everywhere in the world. And all of the books went out of print.

By the 1990s, Rod mostly puttered around his mansion, looking at his awards and memorabilia, and spending his money. He became very well-known among the employees of his local Tower Records, because nearly every night, he’d show up, buy a bunch of CDs, and file them away still in their original packaging in the mammoth music library in his basement.

There were moments in those decades when you could have imagined Rod McKuen making a comeback, when other artists paid tribute to his influence. As early as 1977, for example, Richard Hell released the seminal New York punk track “The Blank Generation.” Careful ears might notice that it sounds exactly like Rod McKuen’s 1959 beatnik satire “The Beat Generation.”

Andy Zax had the profound pleasure of playing these two songs one after the other at a music conference and watching the dean of American rock critics, Robert Christgau, as his jaw dropped. “McKuen probably could have had a giant chunk of the publishing on ‘Blank Generation,’ ” Zax told me. But even before depression really took hold, McKuen generally didn’t care to pursue such matters.

Two decades later, Nirvana recorded a ramshackle demo of McKuen’s song “Seasons in the Sun,” on which the guys charmingly play one another’s instruments.

Between Richard Hell, Kurt Cobain, even an album of covers from one of the guys in Ween, it’s not like it’s impossible to imagine people rediscovering Rod McKuen—but the Rod McKuen machine had shut down. No one was even opening the mail. And so he faded from the cultural landscape.

McKuen died in 2015. The Los Angeles Times obituary noted that he was survived by his half-brother, Edward McKuen Habib.

After McKuen died, Habib was left with a real mess, a mansion full of stuff that no one had dealt with for decades. He threw up his hands. He trashed a lot of it, and gave a lot of stuff away—including handing over all of Rod McKuen’s master tapes to a friend.

And that’s whom they were with when Andy Zax, who specializes in historical audio and archival releases, wondered what was happening with them. Zax had once collected McKuen books and records ironically, but then he decided to go to a late-career McKuen show. “I figured, OK, it’s going to be kitsch. It’ll be hilarious,” he told me. “And he played for I think it was about three hours, with an intermission. And it was one of the greatest live performances I’ve ever seen. He tore people’s hearts out.”

Zax couldn’t shake the master tapes loose, though. After years of unsuccessful negotiations, the friend called Andy and unexpectedly revealed that he’d run out of money to pay for the storage facility that was housing the tapes, and that he was going to have them destroyed. “There are few worse sentences you could say to me,” Zax said grimly, “than ‘I’m going to destroy the master tapes.’ ”

So Zax made a deal. And that’s how Andy Zax, accidental Rod McKuen fan, ended up paying an enormous amount of money every year to store the complete recorded output of Rod McKuen.

There’s a catch, though. He can’t do anything with it, because the people who own the rights to use the material are Edward Habib’s heirs. Habib died in 2018 without any children, and his relatives don’t seem to see what could be so important about all of this, and have been unable to agree on any kind of deal. Zax is the guardian of Rod McKuen’s legacy, but he can’t do anything to perpetuate that legacy.

He’s been trying to get the Library of Congress or some university archive to take them. No one wants the tapes, because Rod McKuen has no cultural profile, but he’ll never recover that profile unless someone uses the tapes. The most salable poet in American history, and now he can’t get anyone to give a shit.

One of the weird contradictions of living in the future is that every artist is at the tip of your fingers, but you can only find who your fingers know to search for. In the not-so-distant past, artists could avoid slipping away thanks to only the physical evidence: a record in a thrift store, a used book with a man in a white turtleneck on its cover, murmuring to the bewildered shopper, “Who am I? To whom did I matter? To whom did I stop mattering?”

The Spotify algorithm, Amazon’s recommendations, they’ll never, ever show you Rod McKuen. Those are designed to direct you towards things that other people like right now. But thrift stores, used bookshops, and Goodwills are, accidentally, perfectly designed to show you things that people liked decades ago, then stopped liking. You just have to look—and to be ready to be confused. “I would say that sometimes the best stuff of all is the stuff that doesn’t make sense,” Zax said. “The stuff that you can’t even figure out a response to, other than to ironically laugh at it, because you don’t have an emotional vocabulary that’ll properly describe what you’re experiencing.”

I definitely don’t have the emotional vocabulary to properly describe the Rod McKuen experience. But I have found myself warming to Rod McKuen, because for so long, he really did mean it. For a solid decade, Rod McKuen was the most sincere man in America. His art came directly from his soul. I remain bewildered by that art, by his fame, by his 80 years of love and lies. But I’m also amazed and heartened that someone this weird, this pure, this totally unique, got to be megafamous in a bygone America. I may never be on the same wavelength as Rod McKuen, but you know what—I still get off on him.

n

n

od

od

his

his

ut

ut

n

n