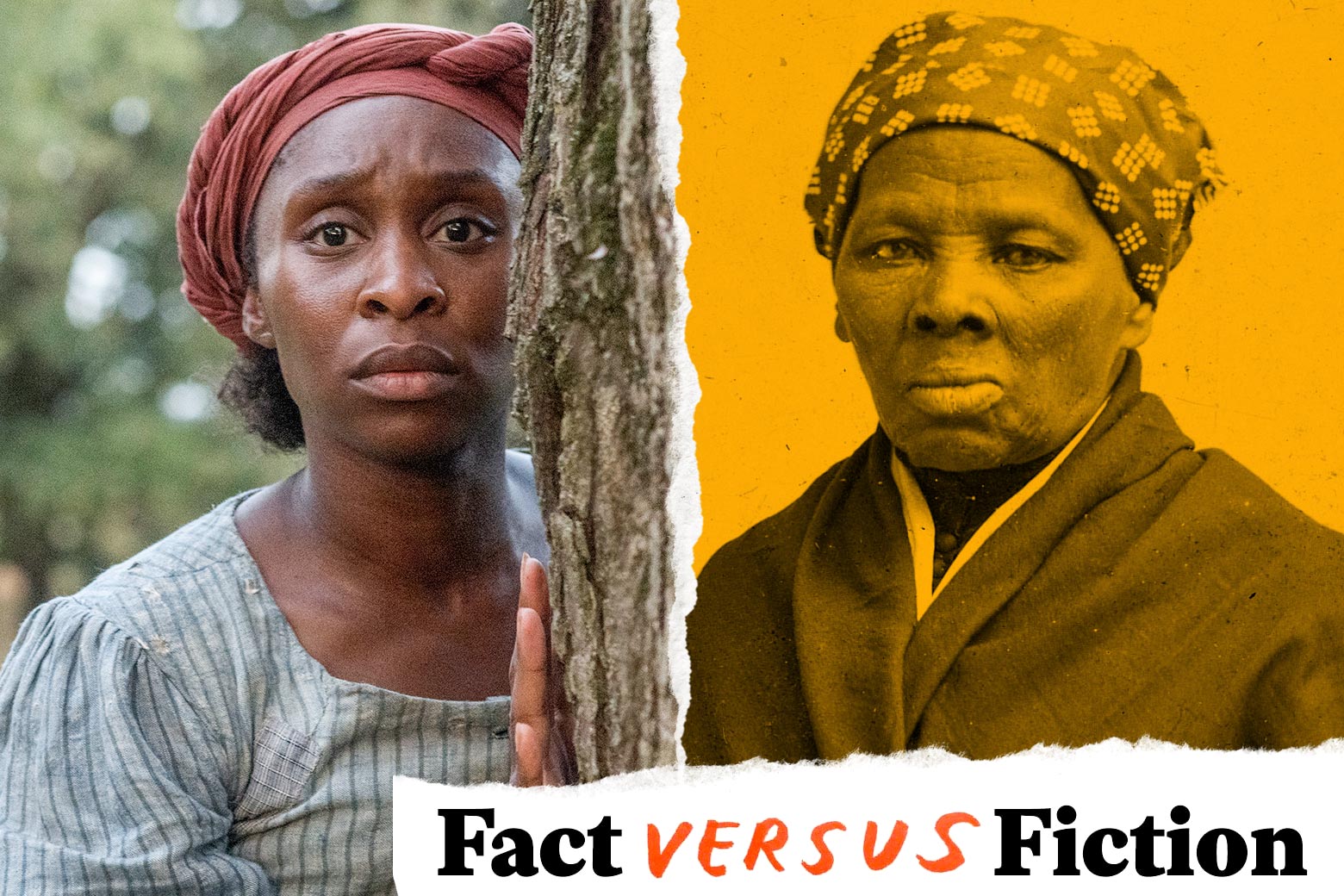

The fact that Harriet is the first feature-length film to tell the story of one of the most famous women in American history may sound improbable, but it’s no less improbable than many of the facts of her life. The new biopic is mostly true to what we know of the real Harriet Tubman, though writer-director Kasi Lemmons (Eve’s Bayou) and co-writer Gregory Allen Howard (Remember the Titans, Ali) take some considerable liberties with both the timeline of events and the creation of several characters. We consulted biographies, articles, primary sources, and a few contemporary historians so we could break down what’s historical record and what’s artistic license.

Tubman’s Early Life as Araminta “Minty” Ross

Just as in the movie, Tubman (played here by Cynthia Erivo) grew up on a farm in Dorchester County, Maryland, where she was born Araminta “Minty” Ross. Though the movie may leave the impression that she only took on the name Harriet Tubman when she reached freedom, she seems to have taken it when she was married, taking Harriet from her mother, Harriet Ross, and Tubman from her husband, a free black man named John Tubman. Despite that, her owners still called her by the name they gave her, as evidenced by the Oct. 3, 1849, advertisement for the return of “Minty” taken out by Tubman’s mistress Eliza Brodess when she eventually escaped.

When the movie opens, Minty and her husband have hired a lawyer to investigate an old will left behind by the great-grandfather of her owner, Edward Brodess, that stipulated that upon the day that Minty’s mother turned 45, she and her children would be set free. Brodess not only refuses to free the family but bans John from visiting Minty on the plantation. This is mostly true to life. The couple did hire a lawyer to look at the will, and he determined that, like Tubman’s father, her mother should have been liberated at the age of 45. But according to historian and Tubman expert Kate Clifford Larson, who consulted on Harriet, the will stipulated that Harriet and her siblings be set free when they turned 45—not at the same time as their mother.

Tubman’s “Spells”

In the movie’s first scene, Tubman experiences one of her “spells,” which often cause her to lose consciousness and seem to give her visions of nearby dangers or events to come. (In an interview with Slate, Lemmons described the “spells” as Tubman’s “Spidey sense.”) As in the movie, Tubman believed that the visions she experienced were messages from God.

It isn’t until later in the movie that we find out that Minty’s “spells” might be the result of a traumatic injury. Just as described in the movie, the real-life Tubman was, as a teenager, struck in the forehead by a 2-pound weight thrown by a white overseer. According to the writer Sarah Hopkins Bradford, who interviewed Tubman for two books about her in the 19th century, the injury “cause[d] her often to fall into a state of somnolency from which it is almost impossible to rouse her.” Twenty-first-century historians have speculated that Tubman might have had narcolepsy, epilepsy, or both.

Harriet’s Escape

In the movie, as in real life, Harriet’s journey to freedom is kicked into high gear upon the death of her master, Edward Brodess. Brodess’ son Gideon (played in the movie by Taylor Swift’s boyfriend, Joe Alwyn) had caught Minty praying for the death of his father after he refused to set her free. Tight on cash and unnerved by her seemingly prophetic praying power, he puts Minty up for sale, and Minty leaves her husband behind in her rapid solo escape. Her father helps her tap into the Underground Railroad through a local free black preacher—based on Dorchester County’s real-life freed slave, preacher, and Tubman collaborator Reverend Samuel Green—and after an almost 100-mile journey, she makes it to Philadelphia.

Harriet really did pray for the death of her master—she admits as much in one of Bradford’s books—but it’s unlikely that she was sold for that reason. In reality, as in the movie, the Brodess family was in dire straits after the death of Edward, and Eliza, his widow, planned to sell slaves to pay off debts. And though Tubman did end up completing her journey alone to Philadelphia, she initially left with two of her brothers, both of whom ended up turning back out of fear.

Gideon Brodess (Joe Alwyn)

Though the Brodesses did have a son, his name was Jonathan, and little is known about him. As those facts suggest, just about everything in the movie that involves this character and his dogged, years-long pursuit of Tubman, up to and including a final standoff in the woods, was invented for the movie.

William Still (Leslie Odom Jr.)

One of the first people Harriet meets in Philadelphia is the black abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor William Still. He helps her get settled in the city and eventually inducts Harriet as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Just as in the movie, William Still really did keep meticulous records of all the people who managed to escape slavery and the horrors they endured, eventually publishing them as The Underground Railroad Records. While there’s no historical evidence that Still greeted Tubman upon her arrival in Philadelphia, it’s not out of the realm of possibility: Still destroyed many of his notes before the Civil War so they couldn’t be used to prosecute fugitives. The notes left behind do indicate that the two certainly worked closely together. He was not only one of the most successful black businessmen in the city but one of the busiest conductors on the Underground Railroad, helping hundreds of fugitive slaves settle in the city or continue farther north.

Marie Buchanon (Janelle Monáe)

The character of Marie Buchanon—a free black woman and successful business owner who takes Tubman in and teaches her how to live as a free woman—is invented for the movie. However, that’s not to say someone like Buchanon couldn’t have existed.

“Moses”

In the movie, Harriet’s first trip back south comes a year after her escape, and it’s to rescue her husband, John. Though he was a free man, his freedom as a black man in the South was exceptionally restricted by the whims of white people, as evidenced by the fact that Edward Brodess could keep him from seeing his wife. But upon returning to Dorchester County, Harriet discovers that, in her absence, John remarried a free woman and is expecting a child with her. While she is still reeling from this news, her father finds her and asks her to help her brothers and a few other runaway hopefuls escape north because the Brodesses were planning to sell them to pay off their mounting debts. Pretty early into their journey, Harriet has to pull a gun on her brother to get him to follow her.

While it’s true that John did remarry in Harriet’s absence, her trip back to Dorchester County wasn’t her first rescue. Before her return for her husband, she rescued her niece Kessiah Jolley Bowley and her niece’s two children in Baltimore with the help of Bowley’s free husband, John. It is true, however, that Tubman would occasionally have to pull her gun on the very people she was helping so that they wouldn’t turn back and give them away. As in the movie, she is often quoted as saying in such situations, “You’ll be free or die,” or, as Still cited in his more contemporary account, “They had to go through or die.”

While Bradford, Tubman’s biographer, claimed that she rescued more than 300 slaves in her missions to the South, Bradford had a tendency to exaggerate. The real number is closer to 70. Similarly, while there isn’t evidence that Tubman became so infamous among slave owners so quickly, it wasn’t long before she was indeed known among abolitionists and conductors as “Moses,” the name by which her feats were often recorded in Still’s book.

Bigger Long (Omar Dorsey)

Upon noticing the escape of Harriet’s brothers, the vengeful Gideon hires Bigger Long, a slave catcher who is rumored to be the best in the area. To his (and my) surprise, Long is a black man. There’s no evidence that the Brodesses hired a slave catcher, but according to a few historians whom I reached out to, it’s not entirely impossible that such a mercenary would have been black. Joshua Rothman, the chair of the University of Alabama history department, told me in an email that “there were surely black slave catchers”:

It would be tricky for such people to operate in the South itself, because in most parts of the South, whites assumed all black people they didn’t know were slaves, and there are plenty of cases of free black people taken into custody, thrown in jail, and sold as slaves themselves. But outside of the South, or even in border states, we know that rings of kidnappers used free black people to lure in their prey, who were far more likely to trust a black person than a white one and who wouldn’t realize they’d been duped until they were en route to being sold as a slave. … And no doubt there were free black people who just decided to do the work themselves and keep all the reward money.

Manisha Sinha, author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, agreed that such people existed but suggested there weren’t many: “There were a few free blacks who were involved in kidnapping rings especially in Northern and border state cities. But they were few and far between and subject to reprisals from a fairly well organized free black community. Many more of course were involved in assisting fugitive slaves and in the abolitionist underground.”

The Fugitive Slave Act

In the movie, Harriet manages several rescue missions, and her reputation as a conductor on the Underground Railroad is well established by the time that the Fugitive Slave Act passes. In reality, the law—which not only made it legal for runaways to be captured and returned to the South but effectively conscripted bystanders into aiding the capture of runaways—was actually passed within months of Tubman’s escape. It was definitely in effect by the time that she returned for her husband.

The Combahee River Raid

At the very end of the movie, we see Harriet two years into the Civil War, giving a speech to a battalion of black soldiers in a prelude to the Combahee River Raid, where she led a group of 150 soldiers in an expedition to destroy Confederate supply lines and rescue about 750 fugitive slaves. In a postscript, we’re told that not only was she the first woman to lead an armed military raid but that she also served during the war as Union spy, nurse, and scout. She dies at 91, surrounded by family.

This, again, is pretty accurate, though at least one historian thinks that Tubman’s role in the raid has been slightly exaggerated. Milton Sernett, professor emeritus of history at Syracuse University, said, “While she was certainly a nurse, spy, and scout for the Union Army, I think the claims that she was the first female general and commanded a raid are wishful thinking.” Regardless of her rank, she certainly played an important role in planning and guiding the raid, and she did, rather improbably for a woman of her time, live to be 91.