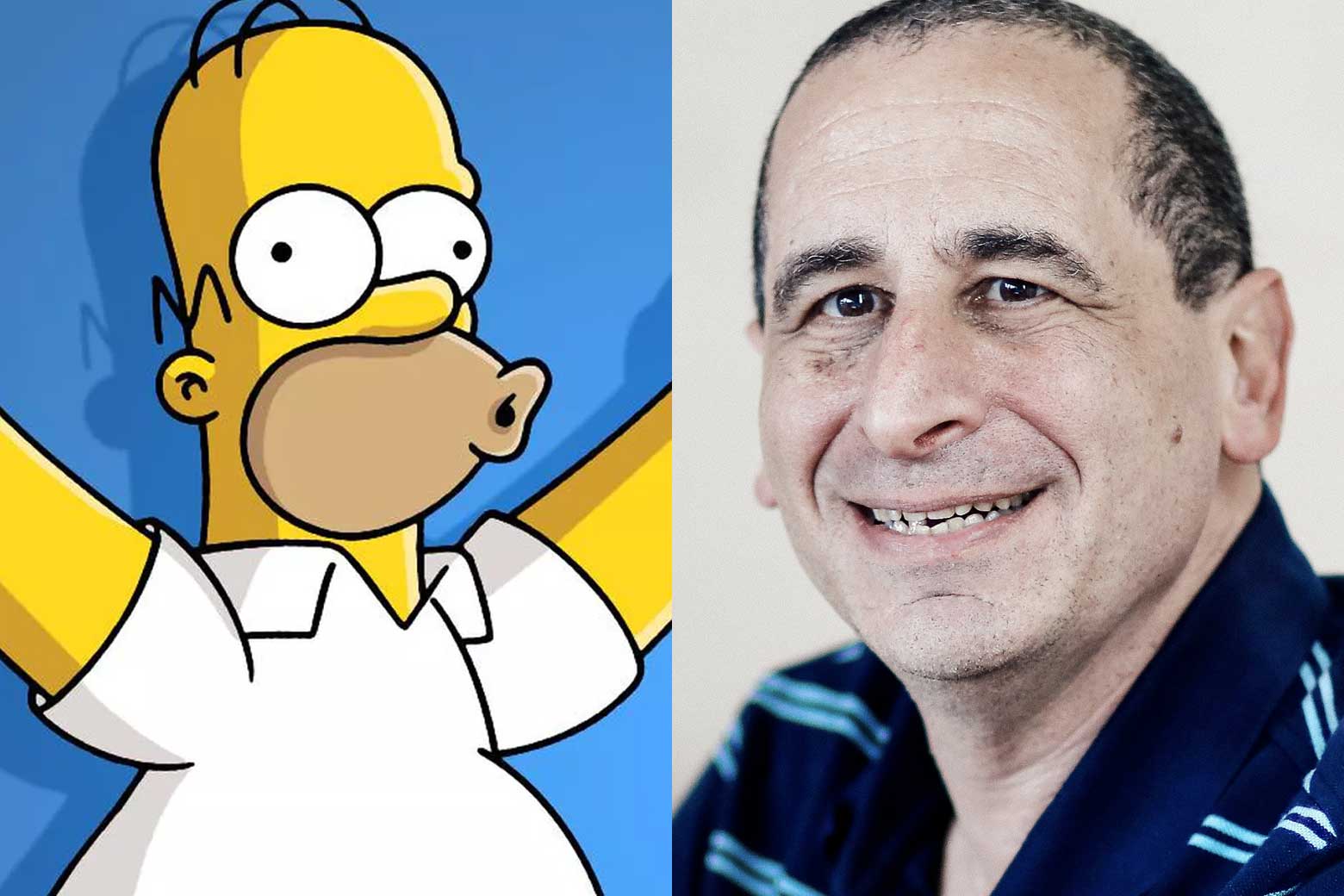

“I’ve hit rock bottom. I’m writing for a cartoon.” This was the thought of Mike Reiss when he joined the writers’ room for The Simpsons in 1989. Thirty years later, he’s worked on all but two seasons of the show, and lived to tell about it in Springfield Confidential: Jokes, Secrets, and Outright Lies From a Lifetime Writing for The Simpsons (co-written with Mathew Klickstein).

On Friday’s The Gist, Mike Pesca talked with Reiss about the trick to writing lines for Homer, how The Simpsons raised the bar for TV comedy, and his favorite episode (which, incidentally, was among “only 50 I had nothing to do with”).

Read an edited version of their conversation below, or stream or download the full discussion via iTunes, Stitcher, Spotify, the Google Play store, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Mike Pesca: When you were first brought on to The Simpsons—as they transitioned from being characters on The Tracey Ullman Show to “we’re going to do the first cartoon in prime-time since The Flintstones”—were you excited by the creative possibilities, or just, “Oh. This is a paycheck”?

Mike Reiss: I would have to go with the latter. I was on a summer break from the lowest-rated show on TV. I was working for It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, and I got the call from Sam Simon saying, “Would you like to work on this? We’re turning The Simpsons into a half-hour show.” I took the job thinking, “I’ve hit rock bottom. I’m writing for a cartoon,” which in 1989 just meant crappy Saturday morning cartoons.

So you write in the book that you wanted to put your best episode first. Which episode was that, and did you know it was the best episode?

I think we actually sort of aired in order, except that we were supposed to debut in September. It was an episode where Marge and Homer go on a date and the Babysitter Bandit comes over and ties up the kids. It was the first episode we got to see fully animated. We had 13 of them in the works. This first one came back and it was a catastrophe. It was a disaster. There was a room full of people watching, nobody laughed. And so The Simpsons literally almost got canceled before it ever came on the air. Our ninth episode was a Christmas show, and we said, “All right, let’s start with the ninth episode. We’ll start at Christmas, and that’ll give us three or four months to fix the other ones.”

In the beginning, it did seem to me that what you were going for was “let’s just take this family to the extreme,” and there was less specificity to the characters. Then everyone got more specific and more relatable. Homer went from just being kind of an angry abuser to … well, that, but some other things, too.

You know, it came from everyone. The three creators of the show: Sam Simon, Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, all have good hearts, and know you can’t get by on snark alone. But Jim Brooks, especially—the man is just like one giant human beating heart. The biggest trick to The Simpsons in those early days was knowing: Thirty seconds of heart at the end of an episode will really shock and move people. But two minutes of heart is way too much. Then suddenly you’re a TGIF show.

So which is the episode that you rank as the best ever?

The one where Lisa finds the bones of an angel. And I have to explain: I’ve worked on all but two seasons of the show. So out of the 650 episodes, there’s only 50 I had nothing to do with, and there’s only 50 I can go home and watch like everybody else.

… And get surprised, and not see the punchline coming.

Yeah. And I go, “Wow, the show seems to be much better without me.” But I don’t tell people that. This one where Lisa finds the bones of an angel was everything I love in The Simpsons. It was a mystery. It was about an issue you never see discussed on TV, about faith versus science.

Yeah. I think my favorite episode was one that you criticized. You regretted or somewhat apologized for insulting the city of New Orleans so much with the Streetcar episode. The songs are fantastic. The interactions around the songs are fantastic. But mostly because of the B plot, with Maggie in the nursery at the Ayn Rand School for Tots, which is really a totally different kind of comedy. There is no dialogue to that, and it’s freaking brilliant. Put that in the Museum of Television and Radio.

I agree, it’s a spectacular episode. And there’s two guys to credit, again, none of them me. I’m the guy crapping up the show! Sam Simon, I think, had the basic notion: Put Marge in Streetcar and let’s make it sort of an allegory for their marriage. Homer is Stanley Kowalski. Great insight (and again, you didn’t see that on a lot of Saturday morning cartoons). And then Jeff Martin wrote the script. He wrote those songs, he wrote the music, the lyrics. And he wrote that whole Maggie subplot on his own.

You point out that animated comedies have this fallback that doesn’t usually work, which is: We’ll save it in animation. If the joke is lame, they figure, they can cut to the animated version or reaction and then it’ll be funny, and on The Simpsons, it’s like, “No. The joke doesn’t work, nothing will save it.” But then how does 10 minutes of no-dialogue action sequences … how does the room know that that works as a joke?

If you can believe this—and we do this for every episode—we listen to the table reading. The cast is there and about 30 or 40 spectators are in the room, and we listen to what gets a laugh. And certainly, you can judge a dialogue joke by that, but you can judge a visual joke that way, too. Somebody will read a paragraph of stage directions, and if it gets a laugh it’ll work in animation. It’s not a perfect system, and very often it drives me crazy that everything’s always got to get a laugh on The Simpsons. And it’s not only got to get a laugh when we do a table reading, but then two months later we see it in rough animation. It’s got to get a laugh then. And then two months later we see it in full-color animation. It’s got to get a laugh then, too. So, woe to you if you wrote a great joke in the first draft, because the same audience has to see it three times and laugh every time for it to finally make it to the air.

You talk about in the book how, at one point there was a joke and your partner Al Jean said, “No, wait a minute. Season 7, Episode 17.” And he knew that it had been done before.

Correct.

But is there any more formalized keeper of the bible, or someone who could tell you when the continuity is right or wrong, or which one’s Rod and which one’s Todd?

The answer is no. We don’t care. And famously, in one episode we said Groundskeeper Willie’s from Glasgow, and in another episode we said he’s from Aberdeen. And the people in Glasgow and Aberdeen care deeply about this. It’s a rivalry. When they play each other in soccer, a fight breaks out over where this drunken janitor is from. So, we don’t care. Luckily there’s the fans, and the Simpsons Wiki, and we use these resources.

I’ve sometimes talked to creators who say, “OK, the way to understand X character is: He always wants to be loved but never says the right thing.” They have these kinds of general rules that really crack a character, and maybe the viewer won’t ever hear them articulated, but they’ll inform the character. Does Homer have any of those rules?

Homer, I love because he’s a comedy writer’s dream. He has every single thing funny wrong with him. He’s fat and bald and stupid and alcoholic and lazy. And then in Season 4, he walks into the pet store and the owner says, “What is that horrible smell?” And George Meyer, one of our writers, goes, “Oh, I guess Homer smells now, too.” John Swartzwelder, who famously wrote 60 episodes of The Simpsons, he said he writes Homer as a dog. No memory, always kind of happy and excited about the next treat. So that’s the only rule of thumb I’ve ever heard.

Do you think if you chronicled The Simpsons over time, you would get a sense of how American humor or humor on television has changed?

Yes. I don’t give The Simpsons a lot of credit for anything. I don’t think it changed the way people think. I don’t think it’s changed politics. The one thing it’s changed is: I think it taught TV, and maybe movies, to work harder. It was the only marching orders we had! Especially the first season, because nobody thought it would last. We said, “Let’s see how much we can pack into an episode.” And we made it really dense, and then I started looking around, all other shows are trying it.

Dense! Every scene, every opportunity, every opportunity to have a joke in the background has a joke in the background.

Right. And this was 1989. The biggest hit on TV was The Cosby Show. And that was a slow show. I thought it was a good show, but nothing ever happened on Cosby. The fastest paced, most irreverent show on TV at that point was The Golden Girls. Just these four old corpses shuffling around an apartment was as dynamic as TV got, so we picked up the pace. And now I can even say I can’t keep up with TV anymore. I watch Brooklyn Nine-Nine or Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. Slow down! And I know this is what we wrought.