“Who needed parents, stability, goals, a future?” Porochista Khakpour, a 40-year-old Iranian American writer, remembers wondering in her late teens. It was the late ’90s, that just-post-end-of-the-Cold-War dreamtime when the economy boomed, the only thing politicians seemed to have to worry about was each other’s sex lives, and the internet was just spreading its tendrils around the world—seeming to promise, then, not just an escape from reality but a glimpse of the reality that was truly to come, one in which borders would crumble, every kind of human connection would be made possible, and true freedom would finally become real.

Khakpour’s life, on paper, represented all that perfectly. In the space of two decades, she had gone from a trembling child refugee from a religious autocracy to a savvy, black-spectacled, drug-and-sex-dabbling student at Sarah Lawrence, at once fresh beyond all comprehension and wise beyond her years. She was an embodiment of that brief era’s pledge that—unlike at any other time in history—a person coming of age could have everything. In her new memoir, Sick, she describes herself as the “girl” in “neo–Malcolm X glasses and black turtleneck … who subsisted on coffee and cigarettes and bagels” and also the girl for whom to lose the dream of being a successful writer would be shattering; the girl who “knew where to drink without being carded” and also the girl who never asked herself if doing something illegal could reap any long-term consequences; the girl “making out with girls casually as if it was nothing to me” and also the girl who never wondered if beginning her romantic life “as if it meant nothing” could, frighteningly, make it nothing, in a bad way, in the long term. Her friends, she writes, “were free spirits, losers, anarchists, skaters, punks, taggers, club kids, strippers, professional junkies.” “Losers”—but not real losers, more people with big, if vague, hopes experimenting in loserdom while awaiting the unfolding of their bright futures.

The presumption was that, for all these people, iconoclasm could be followed naturally by socially approved success, no matter how many societal rules they dared to break for how long. One summer, Khakpour took a literary internship for no pay—never really questioning that it would eventually lead someday to the soft-focus, brilliant adulthood she imagined for herself, the resolution of her insecurities into the intellectual’s version of the perfectly coiffed woman who gets to perch beatifically on Oprah’s couch and tell a redemptive story. That story faded frictionlessly from “[s]wimming too far out at my favorite beach” near Malibu to, Sex and the City–like, “stepping out of a cab in Midtown Manhattan” in a “sensible silk black dress” while grasping a book manuscript—her own, its prose perfected in perfectly quirky “purple pen.”

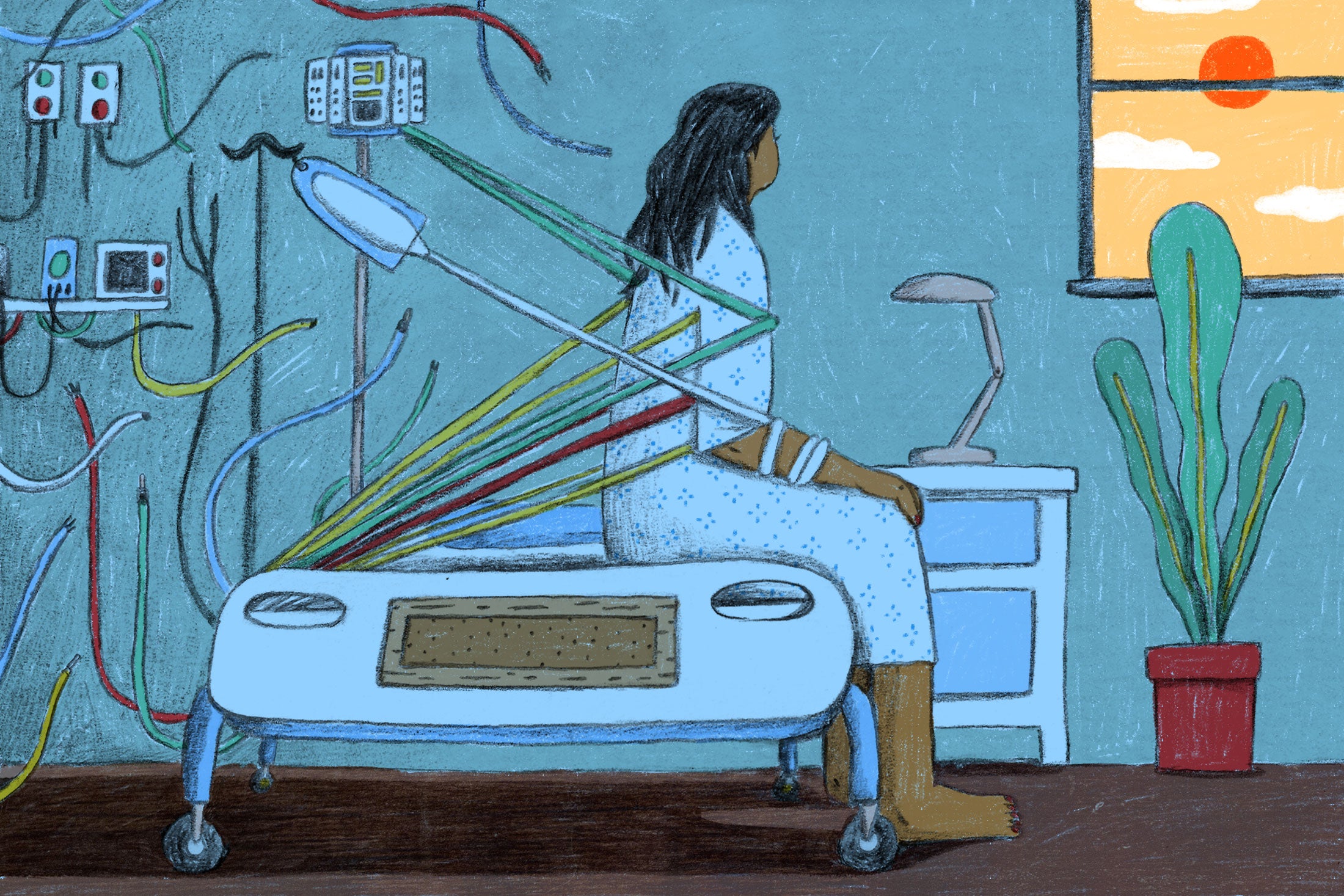

And yet she also felt, even then, that she was “sick.” “I have never been comfortable in my own body” is her book’s first sentence. She feels certain something is “off” about her, and it makes it worse that nobody else seems to notice it. When people compliment her youthful looks, she “accepts it while feeling I’ve deceived them.” It would be another decade before she was diagnosed with the illness that makes up the ostensible theme of this memoir, late-stage Lyme disease.

Late-stage Lyme is a controversial affliction, its biology unclear, its symptoms shifting and various. U.S. government authorities recognize about 16,000 new American cases per year. Activist doctors and some sufferers assert that the epidemic is much more widespread. They say the tick’s bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, slips deep into remote crevasses of the body, evades antibiotics, and then resurges and enters the brain, causing confusion, restlessness, personality changes—or what Khakpour describes as an absolutely terrifying bifurcation of one’s sense of self. “The feeling,” she writes, “was that the illustration on the paperback cover of my second novel, a winged man, had lodged himself in my inner ear cavity” and was screaming at her. Other doctors believe it’s all in the mind, an affliction more properly treated in the psych ward. Experts circle around and around this disagreement, never finding an answer.

The amazing thing about Khakpour’s book is the way she recognizes that any illness in modern life—anything that bumps us off our “path,” that puts us face to face with our imperfections, our limitations, and the uncloseable gap between ourselves and our best selves—inevitably enters the mind. I hope Khakpour’s memoir isn’t relegated to the health section of the bookstore or of Amazon, because it’s not really about Lyme, or not most deeply about Lyme—it’s about modern life. And it’s one of the most chilling, if meandering, portraits of it I’ve read.

Unhealthy, etymologically, derives from the concept unwhole. Sick—which really should be called Alive—depicts how, in one woman’s life, the demands of accomplishing the good life have become arrayed against health. The redemptive illness-to-health memoir—whether it’s emotional illness or physical—has become a huge literary genre. There’s Brené Brown, whose alcoholism and toxic perfectionism were healed by investigating “the gifts of imperfection”; there’s Meghan O’Rourke, whose mysterious autoimmune disease was partially relieved by adopting an attitude of acceptance; there’s Leslie Jamison, whose new book, The Recovering, recounts her slow shift from alcoholism to sobriety. Khakpour’s book is nothing like these books. It’s more like reading the diary of someone you always wanted to be like, only to be transfixed by just how bad being that person can be.

Maybe Khakpour had already been bitten by the toxic Borrelia-bacteria-bearing tick in the late ’90s, but probably she hadn’t. Khakpour retells her doctors’ investigation of when, exactly, she might have been bitten through episodes with various men: Alexander, the “steel heir.” Cameron, the laid-back dude from Westchester. Jerry, the near-perfect-on-paper academic, with whom, for reasons she can never quite understand, things are never quite right until they go really, really wrong. Ryan, the Zen ex-monk, who stuns her by experiencing a sudden psychotic break and beating her. Sam, the ex-con.

All of these men are would-be saviors, which is one of the many contradictions of herself that Khakpour tries to reconcile. She’s also fiercely independent. But there’s something in her she hopes each successive man will be able to “fix.” It might be Borrelia. But it might be the creeping doubt, some hole in her personal narrative, the dissatisfaction and splintered sense of personhood, which many perfectly physically healthy people have.

Not long ago, Oprah filmed a retrospective about her show, which she said, in the ’90s, had fundamentally attempted to proselytize the power of “aha moments.” These are the instants you realize the one thing that will change everything and think to yourself, in Oprah’s words, “Yay, everything’s still working! You’re still growing! You’re still gettin’ it!” Oprah replays a 1999 segment in which she interviewed a mother whose ex-husband had just slaughtered all five of her children. She suggests the onus was on the mother to deal with this situation with perfect self-control. If only she managed her grief right, Oprah assures her, a perfect ending, a fairy tale, would still be possible: “From the ashes of your children will arise something powerful for the rest of the world.” “OK,” the mother whispers, after a long silence. Then she gamely affirms to Oprah: “My reality is the same—except my mindset.”

The segment, now, feels sickening to watch. And yet, as a culture, we’re still obsessed with the promise of such turning points: the sleep app we download, the diet we try, the meditation retreat we attend, the new career we embark on that finally changes everything. With each of her men, Khakpour sought an “aha moment.” Her tale reveals with unsettling clarity that the damage wrought by each of the disappointments is as cumulatively poisoning as any tick bite she might have gotten. And she unmasks the terrifying revelation that any person’s efforts to heal herself, bodily or psychically, have just as good a chance to be wounding as they do to be nourishing.

We think we know everything in the post-Enlightenment world. We know nothing. The Borrelia bacterium is resurging from its lair. It turns out not every problem is manageable with a trick of the psyche, a change in mindset. Trump is the apotheosis of the late 20th-century American fantasy—the man who can change a bitter reality into a different one just by twisting his words—but his election also reflects the last-ditch desperation of a country whose ’90s dreams haven’t turned out to be reality: We see, increasingly, that racism still exists, poverty still exists, just like the rashes that emerged on Khakpour’s unmanageable body.

Khakpour’s prose is beautiful, at once silky and scorching, like the curls of smoke rising from a fire that’s just starting. She’s also a frustrating and contradictory narrator. She never gets well. She defeats herself constantly, running in circles from hope to hope; she reverses apparently peace-inducing epiphanies with, the next page, another doubt. Isn’t that like all of us, though? “Just chill the fuck out,” I wanted to shout at her at times. But the success of the book is its quiet revelation of the ways, deep-set in human nature and amplified by the incessant demands of contemporary society, this just never feels possible. She’s profound, even prophetic, in the in-between passages where she’s muddling along, not quite broken but not quite whole, either.

All of our lives, really, are not parables but the slivered, disordered shards of a shattered mosaic—never adding up, always a piece missing. We can spend our whole lives trying to piece them together into a pretty picture and only look up from this entombing self-focus when it’s very late in the game. There is noticeably little of the world in Sick. Despite Khakpour’s artist-residency-attending, overseas-lecture–jet-setting existence, we see almost nothing of Germany or the gorgeous, exclusive Yaddo artists’ retreat in upstate New York. But this isn’t a criticism. The book feels so, so real. It’s as if I was seeing myself and my peers in a mirror—not an idealized one but one bright-lit, and showing a disturbing, confronting image.

In 2010, Khakpour finally decides to retreat to Santa Fe to do nothing but heal. She cleanses her body with supplements and nourishes her depleted spirit with new mentors, two women. In the genre of the illness memoir, the book would end here. But then Khakpour takes another stab at her dream of New York and meets new, fresh hells. The bees one mentor has given her as therapy die in her care. She experiences pain so bad she can’t stop screaming in the taxi to the emergency room.

In an email to a friend, early in her battle with Lyme, Khakpour wrote, “I am very bad at this.” “This” means being sick, and it’s horrible to think that we’ve created a culture that expects people to do illness well. But we have. In a cemetery for 18th-century British seamen, I once examined epitaphs for the too-soon dead that noted that they met their ends with “resignation.” Now we have to “battle” cancer “bravely.” Is this the expectation now? That we be good at everything—even our pain, even our dying?

There’s an intriguing, gossipy morsel toward the end of Khakpour’s tale: In a respite from illness, a famous writer she calls “Carl” picks her up at a theater by whispering the line, “You look gorgeously, vibrantly alive.” It’s more of a spell Khakpour hopes will be cast on her—another aha moment in the form of a man—than a truth: Not long after, Khakpour ends up in the hospital again. Carl vanishes.

It was only one side of a woman’s life, the gorgeous and vibrant side, that Carl wanted to love. We like recovery, the fall and the rise. We hate unpredictability. In one passage that’s haunted me since I read it, Khakpour writes about the thoughts of suicide that bedeviled her: After many lapses and imperfections, death, she decides, starts to seem like the only possible aha moment whose impact could be assured to stick forever. “That final option that could restore control,” she calls it: The only path that “had not yet”—by revealing itself to be not fully manageable—“rejected me.”

Khakpour has written an unsettling book. But it’s one of lasting merit. It’s something to keep by our desks rather than our bedside tables: not a consolation but a provocation. Perhaps it’s the search for an aha moment, one that resolves conflict and pain for good, that’s making us so unhappy. Maybe it’s not more happy tales we need, but more complicated ones, more difficult ones, more tales that have no clear resolution. Fewer saviors—fewer Ryans and Sams and Carls—and more Khakpours.

Sick by Porochista Khakpour. Harper Perennial.