As anyone who’s seen Veep knows, it’s basically a documentary. Now, having tackled backroom politics in the U.S. with Veep and the U.K. with The Thick of It, Armando Iannucci turns his attention to Soviet Russia with The Death of Stalin, an account of the scheming and backstabbing among the Politburo (the Soviet equivalent of the presidential Cabinet) following the demise of the Soviet dictator in 1953.

Although the blackly comic tone is unchanged, the film is a departure from Iannucci’s earlier work in two ways: It’s his first adaptation (the project was originally a comic book by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin), and the characters are based on actual historical figures. But how much of the over-the-top machinations are based on real events and how much have been embellished for the purposes of satire? We break it all down below.

The Rerun Concert

The film starts off with one of those events that is so absurd it can only be true. No sooner has a performance of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 broadcast over the radio finished than the phone rings with a request direct from the top: Stalin would like a recording of the performance. The beleaguered Radio Moscow producer (Paddy Considine, channeling Victor Spinetti’s beleaguered BBC director in A Hard Day’s Night) immediately locks the doors to the concert hall before the orchestra or any more audience members can leave, drags a conductor out of bed (the previous one having been knocked unconscious), and ropes in more audience members off the street before having the whole concerto played again.

In fact, this all actually happened, although some of the details vary. In reality, everyone had already gone home when Stalin’s request came through. Pianist Maria Yudina was roused out of bed and transported to a studio where a small orchestra and conductor had been assembled. The conductor was not knocked unconscious, but he was so nervous he was incapable of leading the orchestra, as was his replacement. It wasn’t until the third conductor that they found someone able to do the job and a special recording was pressed for Stalin personally. The fictional story departs from real events in that the fateful concert is recorded right before Stalin’s death, while in real life his demise wasn’t until nine years later.

In the film, the incredibly brave Yudina, whose family was killed by the dictator, slips a note into the recording sleeve, telling Stalin just what she thinks of him. In reality, Stalin sent her a gift of 20,000 rubles after receiving the record, and she responded with a thank-you note saying, “I will pray for you day and night and ask the Lord to forgive your great sins before the people and the country.” Ordinarily such lèse-majesté would mean certain death, but Yudina was never arrested. Her courage has made her grave a place of pilgrimage for Russian dissidents since her death in 1970.

Stalin’s Demise

In the film, four Politburo members join Stalin for an evening of watching a Western, drinking, and bantering. After they leave, he suffers a stroke while on his own in his country dacha. The Politburo members rush to his side, ostensibly professing concern but really to fill the power vacuum that will be created by his demise. They summon Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana, and his son, Vasily. All the best doctors having already been arrested and sent to gulags, a team of very young and very old doctors is hastily assembled, though not until after a considerable delay. They pronounce that Stalin has had a cerebral hemorrhage, is paralyzed on his right side, and will not recover. However, the dictator unnerves everyone by briefly waking up from his coma before finally dying three days later.

According to Harrison Salisbury, the New York Times correspondent in Moscow at the time, a bulletin signed by nine examining physicians was issued early on March 3, 1953, announcing that Stalin had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, was unconscious and partly paralyzed, and in critical condition. The attack occurred on the night of March 1.

It is also true that Stalin had had the nine doctors on his existing medical team, most of them Jewish, arrested as part of an officially announced “doctors’ plot” in the fall of 1952, when they were charged with the deaths of leading military and political figures. As a result, at the time of his fatal hemorrhage, he was in the hands of new and unfamiliar practitioners.

In his memoirs and in conversation, Nikita Khrushchev, then first secretary of the Moscow Regional Committee and later Stalin’s successor as first secretary of the Communist Party (i.e., head of government), recalled that he, Stalin’s deputy Georgy Malenkov, Lavrentiy Beria (the head of the NKVD, the feared secret police), and another politician (who was not, as the movie has it, Foreign Secretary Vyacheslav Molotov, disparagingly memorialized in the “cocktail” that bears his name) did watch a movie on Saturday night with Stalin and stayed up drinking till the early hours of Sunday.

Khrushchev writes that the four were summoned back to Stalin’s dacha by his guards around 1 a.m., when they were told the leader was unconscious. They went back home and then returned early Monday morning, at which point they called in the doctors. Salisbury found this delay in getting medical assistance puzzling and possibly sinister, but Iannucci offers the plausible explanation that, rather than foul play, the delay was the result of Soviet bureaucratic inertia that required every decision to be made by committee, with no one wanting to stick their neck out by suggesting a course of action that could go wrong and attract blame.

The suggestion that Stalin’s death was not entirely natural was given added weight by Stalin’s Last Crime, a 2003 book by Vladimir P. Naumov, a Russian historian, and Jonathan Brent, a Yale University Soviet scholar, that revealed information from a previously secret report written by the medical team assembled to attend to the dying leader. Their report originally contained references to extensive stomach hemorrhaging, references that were later excised from the final official medical record. The authors speculate that the stomach bleeding could be a symptom of a Warfarin overdose and note that Khrushchev’s 1970 memoirs recall Beria telling Molotov, “I did him in! I saved all of you,” though this may just be Khrushchev posthumously trashing his old rival.

Stalin’s love of movies is no invention. The dictator had home cinemas in all of his houses, and when historian Simon Sebag Montefiore delved into the dictator’s personal papers made available in 2004 in newly opened Politburo archives, he discovered that Stalin was not only a film buff who identified with lone hero John Wayne riding into town in John Ford Westerns but also “fancied himself a super-movie-producer/director/screenwriter … suggesting titles, ideas and stories, working on scripts and song lyrics, lecturing directors, coaching actors, ordering re-shoots and cuts and, finally, passing the movies for showing.” If Iannucci is ever tempted to do a prequel, surely Stalin, the Producer is rich with possibilities.

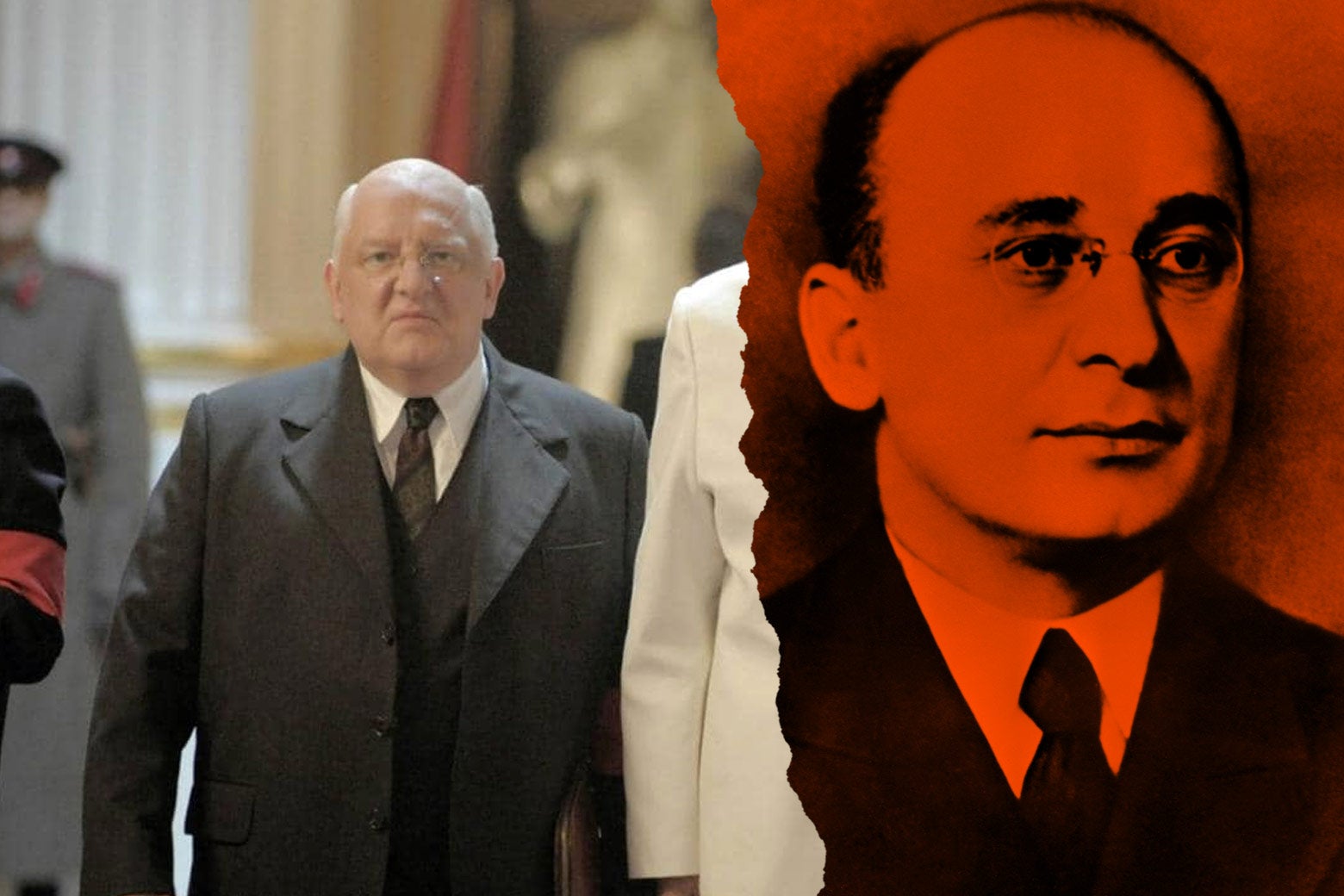

Beria

As depicted by a chillingly malevolent Simon Russell Beale, secret police chief Beria delights in torture both physical and psychological and regards the use of any young female prisoners as a perk of the job.

The movie does not exaggerate. In the 15 years Beria commanded the NKVD, millions of Russians were hauled off to their deaths, some in the notorious Lubyanka prison, others in the gulags. As Beria biographer Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko, who spent 13 years in the camps, wrote:

The gulags existed before Beria, but he was the one who built them on a mass scale. He industrialized the gulag system. Human life had no value for him. … Sometimes he would have his henchmen bring five, six or seven girls to him. … He would walk around in his dressing gown inspecting them. Then he would pull one out by her leg and haul her off to rape her.

Beria was also a ruthless political tactician. The movie shows him ransacking Stalin’s desk before the other Politburo members arrive, retrieving documents that confirm his colleagues signed off on lists of people to be killed, thus giving him leverage. While this rummaging may be invention, the film is accurate in showing that Beria dismissed the army guarding Moscow, replacing them with his own NKVD units, and then canceled the trains carrying large numbers of mourners from the countryside to the city, so that Moscow was under his control.

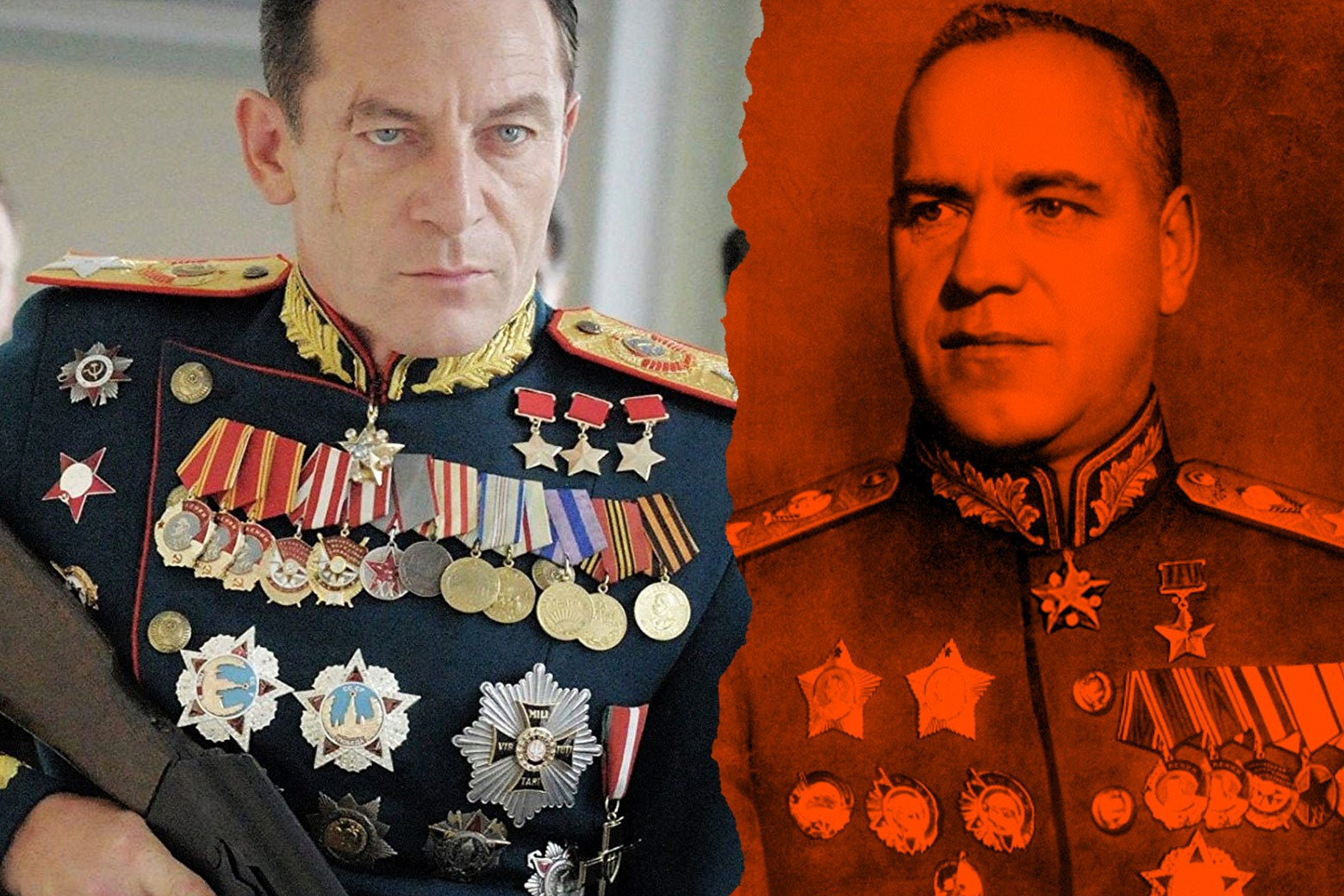

Khrushchev

Beria’s chief opponent is the wily Nikita Khrushchev, played by Steve Buscemi as a sort of combination exasperated small-business owner/cunning municipal politician. Khrushchev goes about winning over his fellow Politburo members, and, most importantly, war hero and military commander Georgy Zhukov (a bluff Jason Isaacs). Zhukov orders the army to get the NKVD to stand down, and, in collusion with Khrushchev, bundles Beria out of a Politburo meeting for a summary trial. Swift justice follows and Beria (spoiler alert) is shot and his body burned.

This is a sped-up version of what actually happened. Khrushchev and his allies did denounce Beria at a committee meeting (held three months after the funeral, not in the immediate aftermath), and Zhukov did storm in with a squad of special forces to arrest the terror chief. But Beria was not whisked off for instant summary justice and an execution. He was tried before a military tribunal at the end of 1953 (without defense representation and without the possibility of appeal) and was sentenced to death there. As in the movie, he begged for the mercy he had never shown to thousands of others.

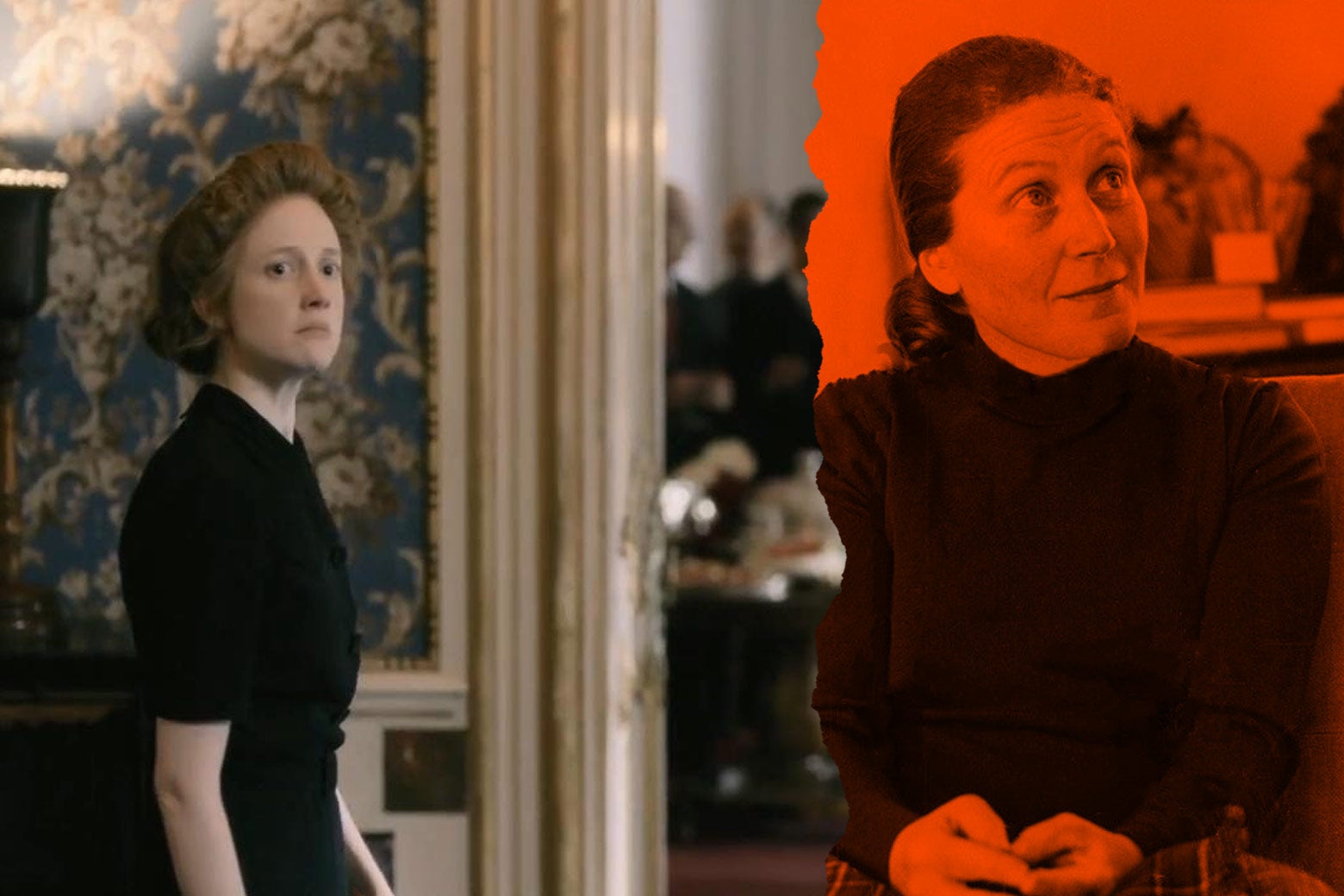

Molotov and His Wife

The movie uses former Python Michael Palin’s innate affability to portray Molotov as a naïf, a man so devoted to the party he doesn’t resent Stalin for arresting his wife, Polina, instead serenely arguing she must have done something to deserve it. Khrushchev tries to use this arrest to ignite Molotov’s resentment of Beria and win his support, but then Beria, having anticipated this, turns up at the foreign minister’s apartment with a released Polina in tow, hoping this act of clemency will mean Molotov throws his support to him.

The truth lies somewhere in between. When Polina was arrested for treason (a trumped-up charge) in 1949, the entire Politburo voted for her arrest. Molotov abstained, but he didn’t defend her. An Israeli Communist Party official recalled asking Molotov about this, writing, “I went up to him and asked, ‘Why did you let them arrest Polina?’ Without moving a muscle in his steely face, he replied, ‘Because I am a member of the Politburo and I must obey Party discipline.’ ”

But then, according to historian Douglas Frantz, it happened that the day of Stalin’s funeral was also Molotov’s birthday and “as they were leaving the mausoleum, Khrushchev and Malenkov wished him a happy birthday … and asked what he would like as a present. ‘Give me back Polina,’ he replied coldly and moved on,” suggesting Molotov’s attitude wasn’t quite so blithe. A week later, Frantz reports, Beria released Polina.

Stalin’s Children

Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana (Andrea Riseborough), is depicted as a slightly steelier version of Selina Meyer’s daughter, Catherine, a fawn among sharks. Both Khrushchev and Beria promise to protect her come what may, but after the latter’s execution, Khrushchev immediately packs her off to exile in Vienna. In fact, Svetlana remained in the Soviet Union working as an academic and translator, until she defected to the U.S. in 1967, a huge propaganda blow to the USSR.

Meanwhile, Stalin’s son, Vasily, was every bit the spoiled, megalomaniac, delusional drunk shown in the film. The younger Stalin was constantly promoted to military positions beyond his abilities and then constantly moved on after screwing up. And, as the film suggests, as the coach of the national hockey team, he did order a plane carrying the players to take off during a snowstorm and then, after the inevitable crash, quickly replaced all the lost team members in the hope his father would never notice. (Stalin didn’t.)