I hope you’re a Werner Herzog fan, because Wall Street is getting grizzly, man. After another day of losses driven by fears over inflation, Federal Reserve tightening, and a potential recession, the S&P 500 has now fallen by more than 20 percent from its previous high—the traditional mark that investors consider the start of a bear market. At one point Monday, every single stock in the index, which tracks America’s largest companies, was down.

Why are investors getting mauled? How much worse could things get? Whom should we blame? Below, I have the answers to your burning questions about this annus ursus horribilis in the market.

Why Is My 401(k) Getting Murdered?

If you want the 2,000-word answer about why stocks have been plunging, you can read Slate’s lengthy explainer from last month. Same fundamentals! But the short version is that investors are worried that the Federal Reserve will have to drastically raise interest rates in order to fight inflation, which has been running at four-decade highs, and that its hikes could push the U.S. economy into a recession. The markets were spooked once again on Friday, when the government’s latest inflation report showed that the consumer price index rose faster than expected in May. As a result, some believe the Fed could speed up its pace of tightening, which has sent stocks plummeting further, and filled Twitter with horrifying Jay Powell memes like this one:

Higher interest rates can hurt stock prices in at least a couple of ways. First, they make it more profitable to park money in less risky assets like government debt, which in turn lowers the value that investors place on profits companies expect to earn in the future (in other words, people won’t pay as much to gamble on stocks when they can make a decent return on Treasurys).

Beyond that, higher rates tend to slow economic growth by raising the cost of borrowing, which can weigh on everything from housing to corporate investment.1 At the moment, there’s widespread fear that the combination of the Fed’s monetary tightening and the aftershocks of the war in Ukraine (which has sent energy and food prices surging) could tip the whole economy into a downturn. The World Bank is already downgrading its expectations for global growth, which could also hurt U.S. corporate profits.

So here’s a simple way to think about the market right now: Scary inflation data is going to be bad news for your 401(k), since it will push the Fed to hike faster and higher.

Why Do People Say It’s a Bear Market When Stocks Are Falling?

The origins of Wall Street’s most enduring cliche apparently lie in early modern Britain, as Jason Zweig explained a couple years back in a great piece for the Wall Street Journal:

According to Anatoly Liberman, a linguist at the University of Minnesota, the use of “bull” and “bear” to refer to financial optimists and pessimists, respectively, originated in Britain in the early 18th century.

“Bull” evoked the bellowing of an eager buyer. “Bear” appears to have come from an early proverbial expression, “to sell the bear’s skin before one has caught the bear”—an apt metaphor for a short sale, in which a trader sells borrowed shares in hopes of buying them back at a lower price.

By the 1850s, traders had begun describing environments in which stocks were going up as “bull markets” and ones where they were falling as “bear markets.” The terms didn’t have any really specific meaning until the mid-20th century, when financial journalists and traders settled on the 20 percent threshold. (So when stocks fall by a fifth from their previous high, we’re in bear territory; when they’re back up by a fifth from their previous low, we’re in bull territory.) As Zweig notes, the distinctions are basically arbitrary—no science went into the idea that a 21 percent drop in the market is substantially different from an 18 percent drop in the market. Still, it’s useful to have shorthands, and calling a 10 percent fall in the market a “correction”—like Wall Streeters are wont to do—and a 20 percent fall a “bear market” makes it quicker for people to talk about this stuff.

How Much Worse Could the Market Get?

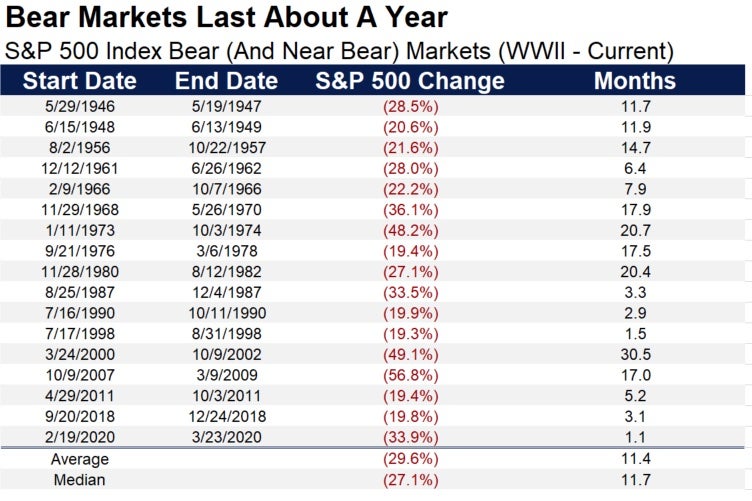

The U.S. has experienced a handful of severe bear markets where it took years for stocks to bottom out and recover. The S&P 500 declined by 49 percent after the dot-com crash of the early 2000s, and didn’t return to its previous high until 2007—only to collapse by even more during the Great Recession. When including a handful of “near” bear markets since World War II, Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist of LPL Financial, calculates the average drop is almost 29 percent.

Plunges into bear territory aren’t always that deep, drawn out, or memorable. To be honest, I’d totally forgotten that the market briefly fell 19 percent in 2018 (the Fed was in the process of hiking rates then, too).

As for the inevitable question of whether now is a good time to invest, I mean, I’m a terrible source of financial advice. But here’s what Detrick tweeted earlier:

Is This Joe Biden’s Fault? I Feel Like Republicans Are Going to Claim This Is All Joe Biden’s Fault.

Obviously the GOP is going to try and blame the Biden administration for any economic or financial misfortune the country faces right now, not least because Donald Trump spent much of the 2020 campaign predicting that the stock market would crash if Biden was elected. Already, we’re seeing some talk of “Biden’s bear market” on Fox News.

In almost any other year, I’d probably end here by saying that presidents have little control over the stock market and that it doesn’t make sense to either blame or credit them for its performance. And to be clear, it’s almost certainly unfair to lay the entire decline we’ve seen this year at Biden’s feet, not the least because asset prices were getting quite bubbly thanks to a long period of low interest rates, and were bound to come down quite a bit whenever the Fed inevitably began hiking back up from zero. What’s more, the S&P is currently just slightly below its value on Biden’s Inauguration Day; it’s mostly just given up the gains it racked up in 2021.

But with all that said, there’s at least a colorable argument that the administration’s policies have played a role in the chain reaction that has sent markets into a tailspin. The primary reason for the steep decline, after all, is that the Fed is trying to bring down high inflation, which may require it to take drastic measures.

Insofar as you’re looking for something to blame, therefore, the right culprit is whoever or whatever force is responsible for sending consumer prices soaring—whether you think that’s the supply chain crisis, the Biden administration’s stimulus spending, the Fed’s own slow response as inflation flared, the war in Ukraine, the natural weirdness of restarting the economy in this semi-post-pandemic era, or some combination including all the above. How you should weigh each of those factors is a complicated question that could take up another article. Either way, as this guy would say, the bear is loose.

1At least in theory; in practice, the connection between interest rates and corporate investment appears to be a bit attenuated. But higher rates can definitely affect housing through the mortgage market.