This piece is part of the Slate 90, a series that examines the multibillion-dollar nonprofit sector. Read all stories from the Slate 90 here, and view the Slate 90 nonprofit rankings here.

If you look up a list of Harvard Business School’s most successful alums, chances are you’ll come across a list of C-suiters and industry moguls who passed through the institution’s prestigious MBA program—men and women like J.P. Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, or billionaire Mike Bloomberg.

But one could argue that, these days, the face of HBS is really a student more like L.L. Cool J.

In 2016, the rapper and actor attended a four-day course called the “Business of Entertainment, Media, and Sports,” which has lately turned into an academic pit stop for successful artists and athletes looking to hone their business know-how. L.L. Cool J—who tweeted a photo of himself in class, hand raised—was joined by NBA stars Chris Paul and Pau Gasol, for instance. Katie Holmes is an alum, too. The celeb appeal of this course has made it the viral symbol of HBS’s massive, growing, and lucrative executive education program, which typically brings midcareer professionals and corporate leaders from around the world to Boston for courses that cost thousands of dollars, and can last from several days to several months. Last year, according to the business school’s annual report, 11,361 students enrolled, up by about 2,000 from a decade earlier. By comparison, HBS has added just 73 students to its traditional MBA program in that time, bringing the total to 1,879.

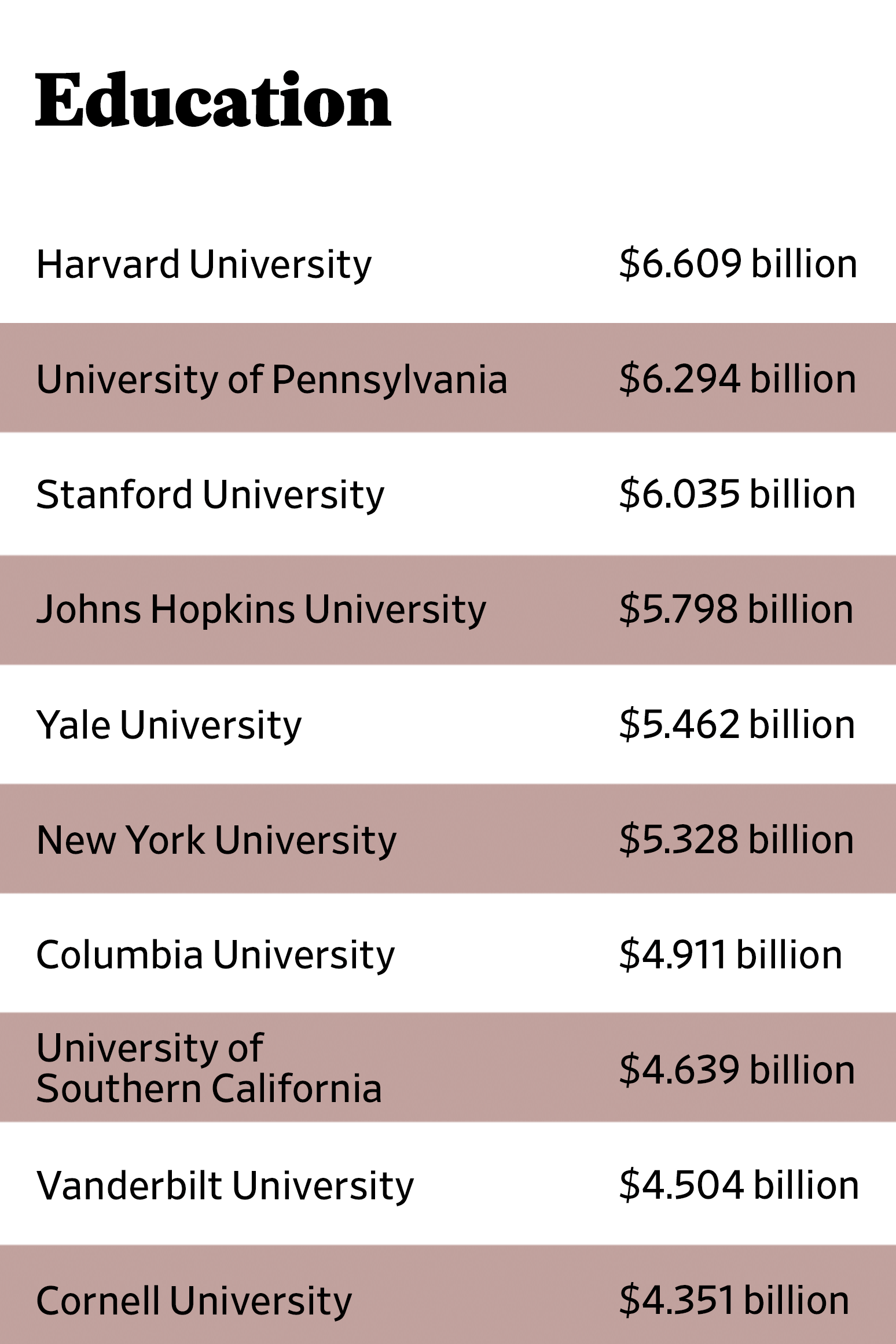

The expansion of executive education at HBS underscores a broader reality about the institution. It may be world-famous for bestowing graduate degrees on tomorrow’s captains of industry and CEOs. But the more closely you look at the business school as, well, a business, the more its other operations can start to look like the main show. (All of those extra students and their sizable tuitions add up to greater revenue for Harvard University, No. 1 in the Slate 90 for education.)

Harvard Business School’s annual financial statement tells much of the story. Unlike most business schools, HBS makes a relatively detailed breakdown of its finances available to the public. (It offers something of, well, a case study in financial transparency.) In 2017, it generated $800 million in revenue: Just over half that came from executive education ($190 million) and HBS’s quietly enormous publishing arm ($220 million). Only $133 million, a mere 16.6 percent, came from MBA tuition and fees. The rest comes from the endowment, donations, and other smaller sources. To give those numbers a little perspective, Stanford Graduate School of Business, which may be the world’s best MBA program depending on who you ask, has a total budget of around $250 million. HBS’s lucrative side-hustles generate more revenue than its main competitor’s entire operations.

Of course, lots of business schools make money from executive education, and carting in managers in need of a mental break for some mid-career resume-sprucing is becoming a more important revenue source for many institutions at a moment when full-time MBA applications are declining overall, at least outside of the elite schools. But aside from having been the first institution to offer such a program way back in the 1940s, and the fact that it’s capable of drawing the odd rapper or jock, what sets Harvard’s executive ed offerings apart from those of its peers are the sheer scale. Based on their most recent public reports, for instance, Stanford’s and Columbia’s business schools, combined, generate roughly $76 million in revenue from executive education—less than 40 percent of Harvard’s haul. That’s all the more impressive given that HBS is (a) located in the Boston area as opposed to New York, and (b) doesn’t even offer an official executive MBA degree. Professionals pay for its courses in order to earn Harvard certificates.

HBS Publishing is a more exotic endeavor—a full-fledged multimedia and academic publishing company that’s related to a traditional, sleepy university press sort of the way an iPhone X is related to an old Nokia Candy Bar handset. While it reports to the business school, it is technically a separate nonprofit subsidiary that belongs to Harvard University. For a long time, it was known best as the distributor of Harvard Business Review, the management bible that lands in the mailboxes of about 250,000 executives, journalists, business professors, and other subscribers every two months, and reaches a respectable 7 million monthly readers on the web. But the magazine and the website are the tip of the HBS publishing iceberg. There are books (the venerable Harvard Business Review Press), a whole variety of online learning tools, and perhaps most uniquely, business case studies. These detailed write-ups of real-world corporate challenges, which students analyze together in groups, are famously the bedrock of the HBS curriculum (MBAs churn through 500 of them during their time in Boston). And while very few schools are as dedicated to teaching via case studies as Harvard, lots use them for at least some class assignments. Because HBS has the oldest, deepest, and best-known repository of such studies, it also sells them in droves: Last year it moved 14.8 million cases, double the total from 2007, and likely more than half of all cases sold in the world, according to the school.

The vast majority of case studies that Harvard sells are written by its own professors. But other institutions, like the University of Virginia Darden School of Business and University of California–Berkeley, also rely on Harvard to distribute their own studies, with HBS taking an undisclosed cut of each sale. When the head of case study publishing at a top business school analogized HBS to the Amazon of business education, he wasn’t far off the mark.

The school’s administration doesn’t shy away from those kinds of comparisons. “We are the platform for distributing ideas in the fields of business and leadership,” said Senior Associate Dean Das Narayandas, who serves as HBS Publishing’s faculty chair, when I brought up the Amazon analogy. But when you bring up the dollar figures involved, a certain New England flintiness sets in. “When we think of publishing, we do not think of it as a commercial operation,” Narayandas told me. “It is yet another way to extend the reach and impact of the intellectual capital of the school.” (He repeated that phrase four times in a half-hour during our chat.)

That may be. But HBS’s big side businesses are both designed to earn it money. HBS Chief Financial Officer Rick Melnick confirmed for me that HBS Publishing ran a roughly $30 million operating surplus in 2016—that’s how nonprofits refer to a profit—which it returned to the business school. (You can more or less track that number on HBS Publishing’s federal 990 filing under the vague heading “payments to affiliates.”) He declined to tell me how much the executive education program nets, but it’s almost certainly quite a bit. One year of tuition for a Harvard MBA costs $73,000 this year, and many get financial aid. Today, L.L. Cool J’s four-day sojourn would cost $10,000.

How you feel about all that may depend a bit on context. As Melnick pointed out to me, for instance, HBS spends $136 million of its own money on faculty research. So you could argue that the money earned by hawking case studies goes back to funding serious academic work. That’s a much more socially useful model than the commercial end of academic publishing, where publicly-held conglomerates like Reed Elsevier make a mint charging for scientific papers produced with federal funding.

On the other hand, its executive education and publishing interests usually help HBS end the year with a financial surplus—which Melnick told me goes toward funding new building projects at the school. “You can either get donations for that kind of thing, or you can use your own money,” he said. Between 2012 and 2016, those efforts involved spending hundreds of millions of dollars primarily to spruce up and build out its executive education digs. During that time, for example, it put the finishing touches on Tata Hall, a curving, 161,000 square foot facility with views of the Charles River, two classrooms and 179 bedrooms. It’s a lovely building—and maybe the symbol of HBS’s future.