On paper, Denmark looks like a paradise for working mothers. There’s the ample paid leave. Danish families are entitled to 52 weeks of it after the birth of a child, meaning parents have a year to care for their new baby without having to worry about their job or their ability to pay rent. Once a mom decides to go back to work, there’s generously subsidized public day care—the government picks up at least three-quarters of the tab—to help them juggle a job and kids. More than 90 percent of children younger than 6 end up enrolled.

Here in America, by comparison, mothers get a paltry 12 weeks of unpaid time off to bond with their infant, and day care can cost more than college. It’s enough to give you an acute case of Scandi envy. Remember when Bernie Sanders said America could stand to be more like Denmark? Their family-friendly approach to government was a big reason why.

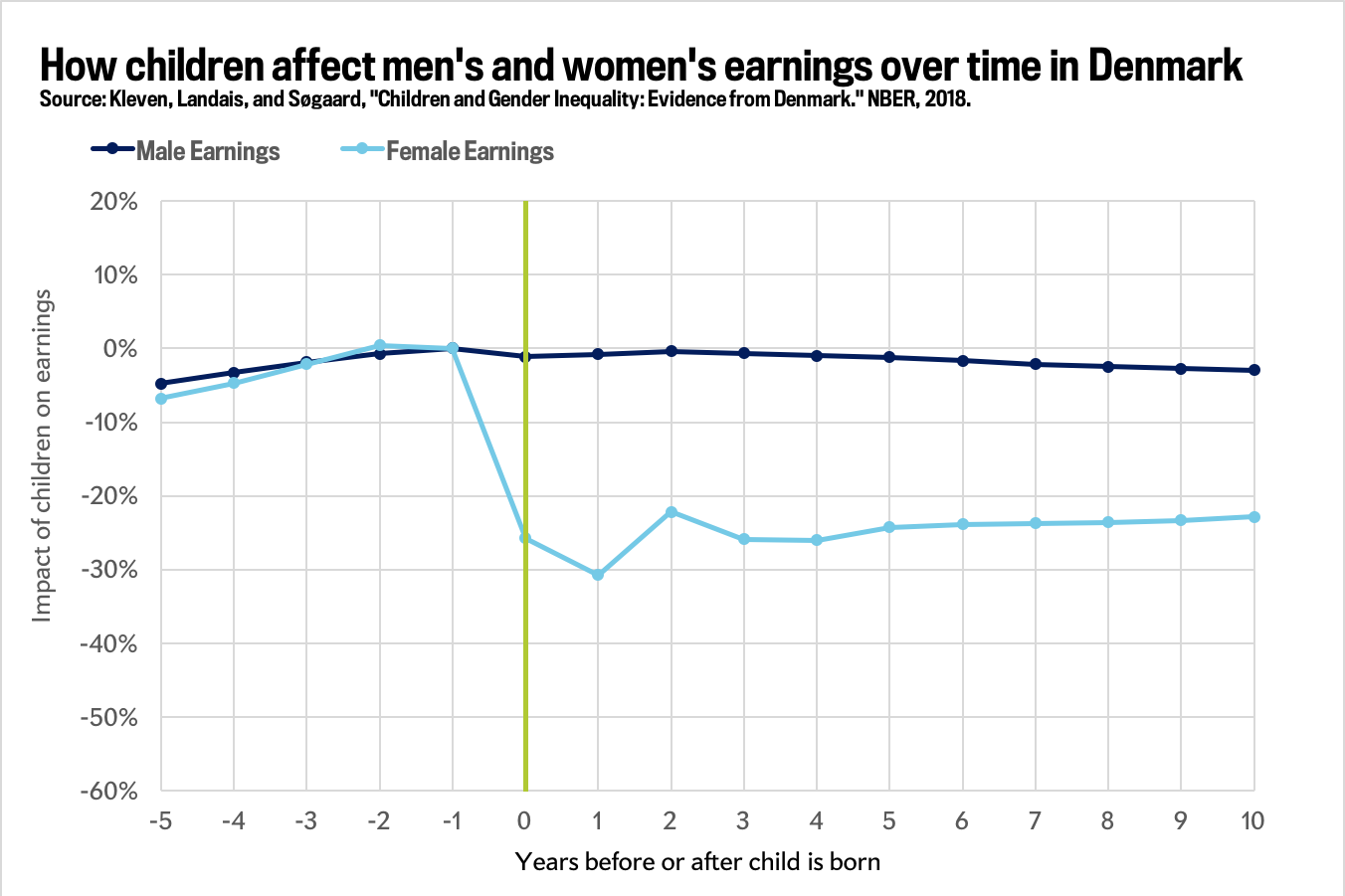

Yet, for all Denmark does to support working parents, it turns out that there, much like here, motherhood is still a pretty devastating career choice. In a new study, a trio of economists used a large cache of government administrative data to look at what happened to the earnings of 470,000 Danish women who gave birth for the first time between 1985 and 2003. The results were dramatic. Before they became parents, the researchers found, men’s and women’s pay grew at a similar pace. After kids, their career paths split. Fathers mostly continued on as if nothing had changed. Mothers, however, saw their earnings quickly collapse by 30 percent on average, compared to what they would have hypothetically earned without children. They became less likely to work at all, but earned lower wages and clocked fewer hours if they did. Worse, their careers never fully recovered. After 10 years, women’s pay was still one-fifth lower than before they had kids.

The problem isn’t even moving in the right direction. The paper, which is still a draft and was released last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, concludes that in 1980, Danish women overall earned 18 percent less than men thanks to to the impact of kids on their careers. In 2013, they earned 20 percent less. “There used to be many different reasons for gender inequality [in Denmark],“ Princeton economist Henrik Kleven, one of the study’s three authors, told me. “Many of those are disappearing over time. Children is the one that isn’t changing.”

Denmark isn’t the only plush, pro-family Scandinavian welfare state where having children still craters women’s earnings. A 2013 study of Swedish couples published in the Journal of Labor Economics found that during the 15 years after giving birth, the pay gap between men and women increased by 32 percentage points. In one of the most philosophically egalitarian nations on earth, mothers’ careers flounder, while fathers’ careers march on.

So, why can’t even Scandinavian women have it all?

Part of the answer may be a story about unintended consequences. If your goal is to help women get back to work and earn a paycheck the size of her male peers’, then providing free or dirt-cheap day care is unambiguously helpful. But generous child leave is more of a mixed bag. On the one hand, it allows women to stay at home and care for their infant without having to quit their job. At the same time, it keeps them out of the workforce for an extended period, which can set anyone back in their careers and possibly discourage them from returning to their old path.

That may especially be a problem for women chasing high-powered careers. Economists have found that women in countries with robust welfare states are more likely to work but less likely to end up in high-paid managerial positions. And while extensive paid leave policies may boost employment for females overall, there’s some evidence they may reduce the earnings of more educated women compared to men. (Once you’ve stepped off the corporate ladder, it can be hard to step back on.) In Denmark and Sweden, women have some of the highest labor-force participation rates in the world, but the labor markets are notoriously gender-segregated, with females much more likely to take jobs in the lower-paid, more flexible public sector.

“With some policies, we say if some is good, more is better, and it may be true,” Francine Blau, a labor economist at Cornell University and a leading expert on the gender wage gap, told me. “With parental leave, it may be true, but it’s complicated.”

Some countries have tried to deal with the downsides of family leave by encouraging mothers and fathers to split it up. But for the policy to work, governments need to essentially force men to take time off. In Denmark, spouses can divide up 32 of their 52 weeks of leave however they please. But as of 2014, men took just 27 days on average, or 8.9 percent of all time off. In Sweden, where parents get a whopping 480 days of paid parental leave, three of those months are reserved exclusively for men. The use-it-or-lose-it policy seems to have been at least somewhat effective at getting men to take more time off for child rearing: The country used to have a national joke about dads using their parental leave to go moose hunting; today’s stereotype of the Swedish dad is that of an enlightened male pushing a stroller. Still, the Swedes haven’t evened things out entirely. As of 2014, men still only took about 123 days off, compared to 356 for women.

We also don’t know even know whether policies that nudge fathers to take time off actually help women’s careers long-term. As one article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives explained last year, “[T]o date, there is no evidence of beneficial impacts of paternity leave rights on mothers’ careers.”

Taking time off immediately after giving birth isn’t the only thing that hobbles mothers’ careers in Sweden and Denmark. In both countries, a lot of women simply work part time. In Sweden, some of that may be the result of yet another public policy intended to be family-friendly: parents with young children there are entitled to part-time work schedules. (Notably, feminists in Denmark have opposed implementing a similar policy, arguing that it would be bad for equality.) But much of this also likely boils down to cultural preferences. In their recent working paper, Kleven and his co-authors point out that around 60 percent of adults in Denmark and Sweden believe that women with school-age children should work part time. They also find that how much mothers work after giving birth seems to be influenced by their own upbringings. “In traditional families where the mother works very little compared to the father, their daughter incurs a larger child penalty when she eventually becomes a mother herself,” they write.

Tradition can be hard to budge. In Denmark, labor unions and fathers’ rights groups have actually advocated for a Swedish-style use-it-or-lose-it policy that would require dads to take more leave. Many men would apparently love an excuse to spend more time walking around Copenhagen in a BabyBjörn. But along with employers, they’ve run into opposition from mothers, who don’t want to lose their own time with the kids, even if it means they bear more domestic responsibility. This brings up a point that’s sometimes easy to overlook: In the end, many women may be happy to trade some of their career for a family life, especially when government policies make it into less of an all-or-nothing deal.

So what does all of this mean for the U.S., where we are woefully behind on parental leave and child care policy? To some degree, the situation in Denmark and Sweden—wealthy, progressive countries where cultural expectations are still driving some of the gender gap—suggests that there’s only so much public policy can do. As the authors of the Swedish couples study put it, “so long as family responsibilities are unequally shared, the gender gap is not likely to close and not even to narrow significantly.”

With all of that said, there are still good reasons to yearn for a dose of Nordic-style social democracy here in the states. It might not be a miracle cure for gender inequality. But paid leave and subsidized child care do make being a parent less of nightmare—especially if you do decide to try to balance work and children. Plus, the pay gap between men and women in Denmark and Sweden who choose to work full time is still smaller than it is in the U.S., meaning that they’re arguably closer to achieving equal pay for equal work than we are. It may not be utopia, but it’s better than here.