After a weekend of hate-watching football, the commander-in-chief has finally turned his attention to the ongoing crisis in Puerto Rico. “This is an island sitting in the middle of an ocean,” President Trump said on Tuesday, explaining the difficulty in providing aid. “It’s a big ocean, it’s a very big ocean.”

Trump is right that Puerto Rican geography poses unique challenges, particularly for electricity provision and the affordability of consumer goods. But in other ways, the 1,000 miles separating Puerto Rico from the U.S. mainland don’t constitute much of a barrier. Over the past decade, the single most pronounced trend in American migration has been north and west, out of Puerto Rico and into states such as Florida. Puerto Rico endured a net loss of 446,000 people between 2005 and 2015, amounting to more than 10 percent of the population. Out-migration occurred in nearly every county, with the biggest drop in San Juan, which lost 40,000 residents.

This week, as much of the island lies in ruins, politicians are warning that short of both immediate and long-term aid, Puerto Rico is about to endure a hurricane-induced exodus on par with the one Katrina wrought in New Orleans in 2005. Katrina displaced more than 400,000 people, half of them from New Orleans. The city’s population fell by 50 percent and has only partially recovered in the 12 years since.

Unlike residents of storm-ravaged island nations such as Antigua and Barbuda, Puerto Ricans always have a compelling Plan B: They can move to the mainland United States. On Sunday, Puerto Rico Gov. Ricardo Rosselló warned the Washington Post that without a comprehensive aid package, there would be “massive migration to other states, which will bring a whole host of other problems to Puerto Rico and the states.”

“If we want to avert massive exodus in Puerto Rico, we must take action now,” the governor reiterated on Monday. Rep. Nydia Velazquez, the Puerto Rican congresswoman who represents parts of Brooklyn and Queens, said the arrivals could be “unprecedented.”

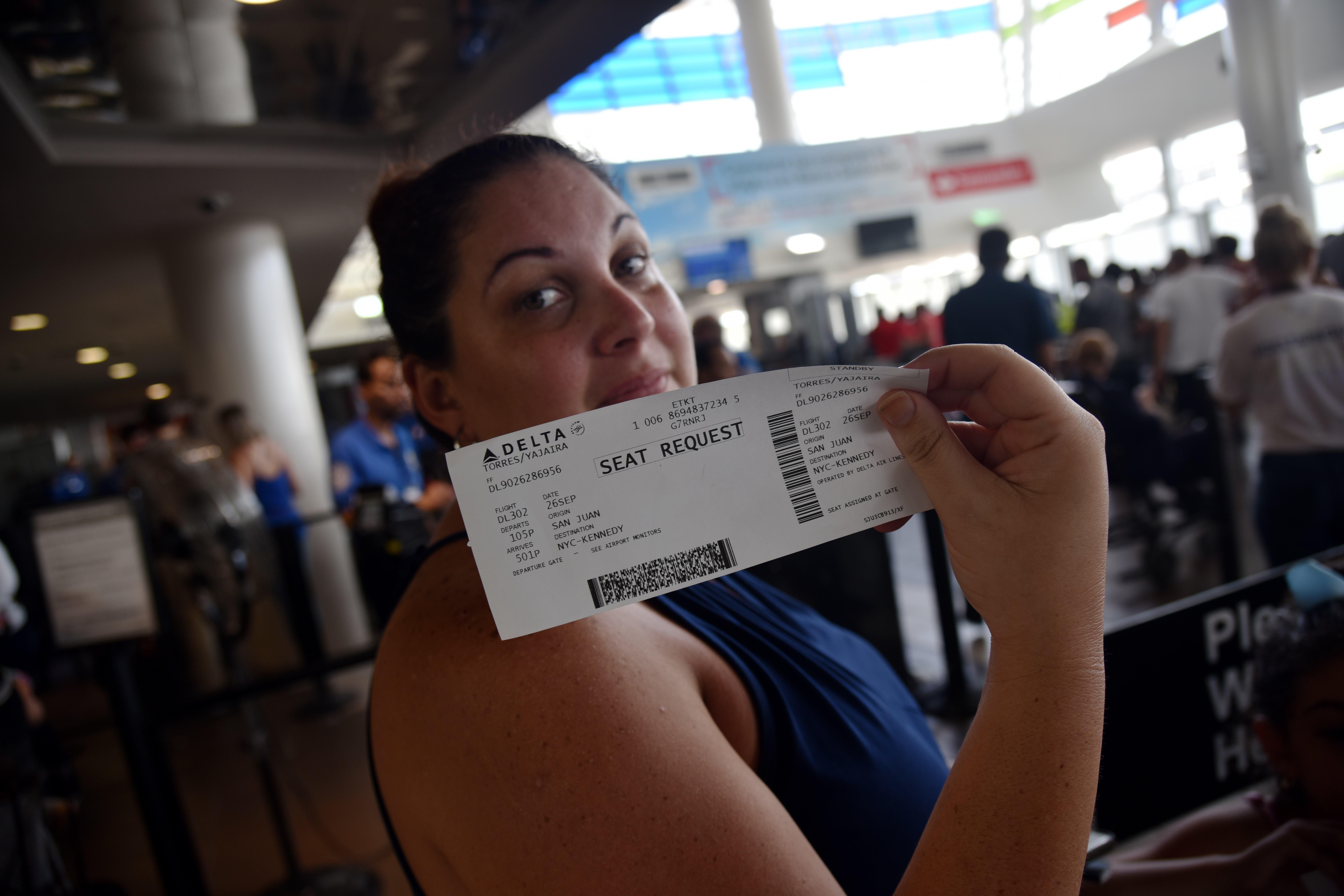

It may already be beginning. At the San Juan airport, operating at a reduced capacity on the strength of two-dozen generators, thousands of people are waiting to leave, and the stand-by lists for commercial flights are in the tens of thousands.

And while it’s harder to move from San Juan to New York than it is to drive down Interstate 10 from New Orleans to Houston, Puerto Ricans who move north would also be following a well-worn path that their relatives and neighbors have been taking since the 1950s. In a piece written before Hurricane Irma skirted the island earlier this month, the demographer Lyman Stone pointed to two recent papers on hurricane-induced migration. One study on natural disasters in U.S. counties concluded that severe disasters increased out-migration, lowered home prices, and increased poverty rates—and that the dynamic was particularly relevant in areas that face high disaster risk or lack other economic advantages. Another found that hurricanes increased immigration to the U.S., particularly legal immigration from countries that already had large existing populations in the U.S.

The case of Puerto Rico, it seems, lies somewhere between the two. Before the hurricane, Puerto Ricans mostly moved to the mainland for work or for family. There will be plenty of reconstruction work on the island, clearly, but fundamental sectors of the economy—agriculture and tourism, for example—can’t be repaired in months. Some workers may look to the states. Those relocating for family reasons may take this as the push they needed.

This will exacerbate the structural challenges Puerto Rico faces. If large numbers of Puerto Ricans leave, the long-term recovery plan—using public-private partnerships to draw big investments into public works projects like fixing the island’s hated power authority—won’t pencil out. A restructuring agreement with the heavily indebted territory’s bondholders and pensioners will be more difficult and ultimately more painful for both retirees and taxpayers if the island’s population takes a big hit. (Hedge funds will suffer too, but I don’t think anyone but the president is concerned about that right now.)

On the mainland, all this has a political component that may hasten GOP action in Washington. Puerto Ricans vote for their own parties particular to the island in addition to participating in two-party primaries for U.S. president. Rosselló, whose party supports Puerto Rican statehood, has tried to assuage the statehood-skeptical GOP by arguing the island could be a swing state. Still, despite the fact that its nonvoting congressional representative is currently a Republican, there’s a consensus that the island would vote Democratic. Puerto Rican districts on the mainland tend to be solidly blue.

Between 2005 and 2013, more than 20 percent of migrants from the island settled in Florida, where they have been joined by 72,000 Puerto Ricans coming from other states. Thanks to that shift—a 110 percent change from 2000 to 2014—Florida has surpassed New York as the state with the largest number of self-identified Puerto Ricans. Each major party has said that new population represents an opportunity; Rep. Darren Soto, the state’s first Puerto Rican congressman and a Democrat, thought Puerto Ricans delivered the state for Barack Obama in 2012.

To make matters more complicated, Pew reports that Puerto Ricans who have migrated to the mainland are further to the left on social issues than their counterparts on the island. Whether this is self-selection or the effects of big-city culture isn’t clear. Still, the percent of Puerto Ricans who think abortion should be illegal drops from 77 percent (island) to 50 percent (island-to-mainland) to 42 percent (born on mainland); the percent who think same-sex marriage should be illegal drops from 55 percent (island) to 40 percent (island-to-mainland) to 29 percent (born on mainland). All of this suggests that a Puerto Rican exodus would inject a lot of blue voters into purple states.

That’s a very cynical reason for the GOP Congress to prepare a serious aid package for Puerto Rico that looks beyond the damage caused by Hurricane Maria. But it’s one they are surely contemplating in private.