The imperial family of Japan is facing a looming succession crisis. Current law forbids female family members and their children from ascending to the throne, meaning only male children of male family members may become emperor someday.

But of the 19 people in the Japanese royal family, just five are men, including 83-year-old Emperor Akihito, who plans to abdicate his position next year. He’ll pass the throne to his eldest son, Crown Prince Naruhito. Naruhito has no sons, so he’ll pass it to his younger brother Akishino. Akishino’s only son and Akihito’s only male grandchild, 10-year-old Hisahito, is next in line. If he doesn’t have any sons, there will be no one left to take his place.

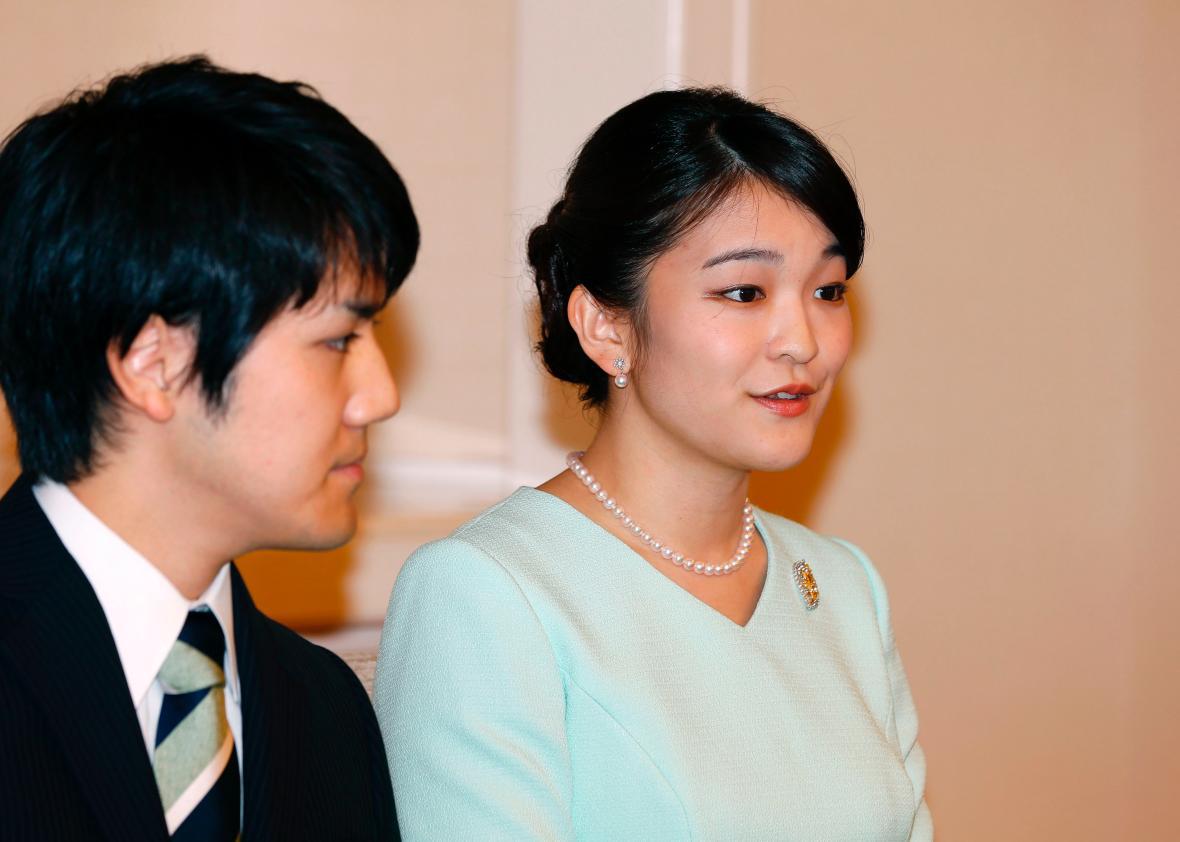

The fast-approaching end of Akihito’s reign isn’t the only cause for concern among those invested in the future of Japanese monarchy. On Sunday morning, Princess Mako, Akihito’s oldest grandchild and Akishino’s oldest child, announced her engagement to a commoner. Japanese law dictates that male royals can marry outside the imperial family and retain their status, but women cannot. When 25-year-old Mako marries legal assistant Kei Komuro, her college boyfriend, she’ll finally get the right to vote but forfeit her allowance from the government, her title, and her last name.

A large majority of Japanese residents—86 percent, according to a May 2017 poll—believe that women should be eligible for the throne, and 59 percent think the children of female family members should also count in the line of succession. Sixty-one percent want princesses to be able to stay in the imperial family after their marriages to commoners, helping to expand the family tree as those couples grew their own branches of descendants. Now, Japanese legislators must decide which is more important: the continued existence of a dwindling imperial bloodline or its strict patrilineal heritage.

The country’s parliament is already in the midst of shaking up the imperial rules. Over the summer, legislators passed a popular bill allowing Akihito to abdicate the throne as per his wishes, an option that was previously forbidden to monarchs who had to serve for life. More conservative members of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party worried that considering such a bill would force them to open debate on the female succession issue, which is governed by the same 1947 law. Abe shut down these nascent debates earlier this year, suggesting that some former “collateral” branches of the imperial family, which were cut off with that 1947 law, be let back in or have their sons adopted by current princes to expand the pool of potential heirs. The largest opposition party in Japan, the Democratic Party, is advocating for a legal shift that would let women already in the family to reign instead.

By some accounts, even Emperor Akihito supports such a change. Empresses are not unheard of in Japan: Though emperors used to have concubines to increase the likelihood of producing male heirs, eight women in the family have sat on the throne in the 125 recorded generations of the imperial family. They were largely considered stand-ins until patrilineal successors could take over. There are few good arguments beside tradition for the endurance of government-supported monarchs, and even fewer for the restriction of the throne to men. Mako could just as easily perform the duties of an empress, minimal as they are, as her grandfather, and imperial genes will persist in her future children as much as they will in her brother’s. There’s another word for a tradition that would rather reintegrate families who have been commoners for generations into the imperial line than treat women as equally valued members: sexism.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom is about to see a recent measure for monarchical gender equality finally come into play. Kensington Palace announced early Monday morning that Kate Middleton is pregnant with her third child, adding another heir to Prince William’s growing lineup. In previous generations, a new baby boy would have taken the place of older sister Charlotte, baby No. 2, in the line of succession. But a law passed soon after Middleton joined the family in 2011 ensured that any daughter of a U.K. monarch would have an equal shot at ascending to the throne as a son would. Royal families are indefensible mooches on the government, but as long as they exist, a Charlotte or a Mako shouldn’t have to see her rightful place on the throne usurped by an annoying younger brother.