If you’re not a parent, you may remember shopping for school supplies as an enjoyably quaint activity: a quick trip to the store to pick out a new Trapper Keeper, and some shiny folders, along with a few boxes of crayons, pencils, and a bright pink eraser.

When I asked parents on Facebook to share their children’s lists, my inbox started filling up immediately with exasperated responses. One mother who has two kids in public school outside Dallas said she spent $180 fulfilling their “ridiculous” lists this year. Her third-grader’s extensive list includes six plastic pocket folders with brads (specifically: red, blue, yellow, orange, green, and purple), Fiskars-brand scissors (sharp point), a four-pack of Expo markers, and 48 No. 2 pencils. As the lists have become cumbersome to fulfill, PTAs and online services have stepped in to bundle supplies for a fee. (Many parents who contributed to this story asked that their names not be used to avoid upsetting their children’s teachers and school administrators.)

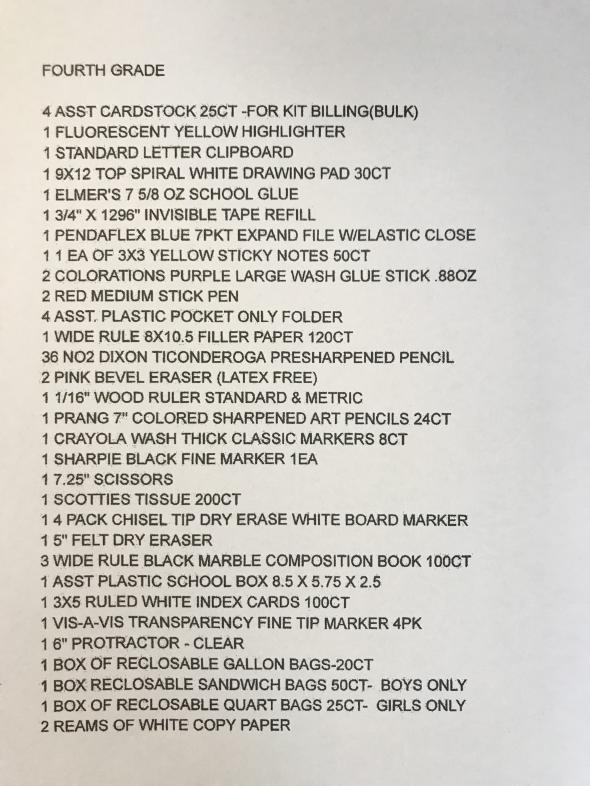

Today, many parents describe it differently. School-supply lists are now often shockingly long, requesting dozens of specific and sometimes expensive items. They include particular brands: Prang watercolors, Ticonderoga pencils, Elmer’s glue sticks. “Pens” are no longer good enough; only “Black Papermate Flair Porous-Point Medium-Point Pens” will do. And the definition of “school supplies” has expanded to include items like tissues, sanitizing wipes, locker shelves, and plastic baggies. The requests are the stuff of parody in parenting magazines and laments on private Facebook pages. Comedian Dana Blizzard’s response to the belly-aching was passed around widely on Facebook this week. “I’ve been noticing lately, when people are doing their back to school shopping, everybody’s complaining,” she tells the camera, tossing microwaves and jugs of glue into her cart as she wheels through Target. “My thing is: Listen. It’s the end of August. I will give you anything to take my kids.”

Holly Allen

The lists vary widely between classrooms and schools, even within the same city. One single working mother whose daughter is starting kindergarten on the Upper East Side of Manhattan estimates that fulfilling the detailed 38-item list will cost her $300. The list includes foaming hand-soap (Babyganics or Method brand), four rolls of Bounty Select-a-Size paper towels, and Staples white shipping labels (2”-by-4”). “I think it’s absurd,” the mother told me. No working parent “has this kind of money or leisure time to surf Amazon Prime for this crap.” Meanwhile, the father of a second-grader in Park Slope, Brooklyn, got a note asking for just $20 to cover four simple items that the teacher will purchase for the students. “Over the years I have felt that school supply lists have become expensive and specific,” the teacher wrote to parents. “It is my hope that by eliminating the expense of exhaustive supply lists, budgets might be freed up for your family and field trip admission over the course of the school year.”

The short explanation for supply inflation is that as education budgets shrink so, too, do schools’ stores of basic items. Teachers routinely spend hundreds of dollars of their own money on classroom supplies, especially in poor areas. Jane Steffler, who recently retired as a kindergarten teacher outside Chicago, had free access to a well-stocked supply room when she taught at a wealthy district in the 1970s. At the low-income district she worked for in the late 1980s, supplies were kept in a locked closet but could still be freely requested. Later, the supply room closed for good, and teachers were given a small fixed budget for their classrooms—forced to spend their own money or make requests for parents if they ran out of supplies during the school year. “We really tried to not ask more of the parents than we thought we needed,” she said. “I don’t know a teacher who hasn’t paid for everything in their room.” Another teacher told me she usually spends about $500 a year on stocking her classroom. Some teachers now set up Amazon wish-lists or otherwise let parents know how they can contribute beyond basic supplies.

Long lists aren’t strictly a public school phenomenon, but that seems to be where the most public parental umbrage is focused. One teacher told me that at his wealthy private school, spare lockers were stuffed to the brim with leftover supplies, and yet some classroom’s annual lists cost parents $150 to fulfill. Complaints were rare. At the low-income public school at which he taught before that, teachers worked hard to keep supply lists sparse, but they had to account for the fact that only about half of the students would arrive in September with all the requested items. When he wanted to make sure that every child in the classroom had access to certain items, he simply bought them himself.

Paltry budgets explain why many lists are so long—though I admit it’s hard for me to peruse the Upper East Side kindergarten’s list and wonder if kids really need six different Crayola marker packs to succeed. (In case you’re curious: thin “classic,” thin “bold,” thick “classic,” thick “bold,” thick “tropical,” and “multicultural.”) But why do teachers request such specific brands and sizes? In many cases, they pool all the supplies together in order to help families who can’t afford to contribute supplies. It is not uncommon in low-income districts for some children to show up with no supplies from home. And quality really does vary widely, teachers told me: Cheap pencils snap frequently and sharpen unevenly; no-name watercolors are more like useless plastic pods than paint. Most teachers do factor in the cost for parents when making their lists. “One year some parents got together and made a large push for all eco-friendly supplies,” described one teacher, who declined the request due to cost. “While their hearts were in the right place, they were very out of touch with the population of the families at the school since roughly 60 percent fall below the poverty line.”

The cost of all these pens, pencils, and Fiskars Blunt-Tip Safety Scissors is obvious. Less obvious is who is paying the price. When I asked parents on Facebook for feedback on their children’s lists, I got more than 40 responses. Two were from men replying in their capacity as teachers, and two of them were from fathers with information about their children’s supply lists. The rest were from mothers. Many of the women sent along homemade spreadsheets and described detailed plans to visit multiple stores to save money; they keep track of local sales, and devise systems for consolidating leftover supplies at the end of the school year and preparing them for next year’s requests. Meanwhile, women make up about three-quarters of public school teachers—the ones spending hundreds of dollars of their own salaries to stock their classrooms. As education budgets shrivel so dramatically that Kleenex have become luxury items, it’s women who are spending the time and money to keep schools running.