R. Kelly’s alleged sexual misdeeds have been in the public record for decades. Half his lifetime ago, in 1994, he married his then-15-year-old protégée Aaliyah with a falsified legal document. At the turn of the millennium, thanks to the reporting of Jim DeRogatis and Abdon M. Pallasch at the Chicago Sun-Times, the world learned that Kelly had paid several settlements to the families of underage girls he’d allegedly raped. Soon after came the actual videotape of a man who looked like Kelly engaged in sexual activity with a girl whom witnesses identified as his then-14-year-old goddaughter. He was later acquitted of charges that he’d produced that piece of child pornography.

In the years that followed, Kelly had no trouble getting gigs. He made albums, toured arenas and stadia, and made fluffy appearances on late-night shows. After BuzzFeed published new allegations against the singer this week from parents and former lovers who say he sexually manipulates and essentially brainwashes teen girls with promises of music stardom, the site asked the publicists of 43 former Kelly collaborators if their clients would ever work with him again. After giving the stars’ representatives “at least 24 hours to respond,” very few had gotten back to the site. Those who did either said they had no comment or couldn’t reach their clients for comment.

As the Outline rightly pointed out in a post yesterday, it’s hard to draw any conclusions from this seemingly clever conceit. Celebrities rarely comment on anything, especially in a relatively short period of time on an extremely touchy issue that doesn’t directly concern them. They would have nothing to gain from staking out any definitive ground on R. Kelly, even if they fully intend to never work with him again. Some of the stars on BuzzFeed’s list hadn’t worked with Kelly in many years: Celine Dion made one song with him in 1998, for example, and Keri Hilson’s Kelly collaboration dropped in 2009.

Still, the vast majority of the artists on the list worked with Kelly after all-but-irrefutable evidence of his pattern of preying on young girls became public. They knew that dozens of people had accused him of child rape, and they worked with him anyway. Their participation in his career both elevated and sanitized his public profile, showing music fans that if Mary J. Blige, Nas, Chance the Rapper, and Pharrell (the Happy guy!) were cool with Kelly, we should probably be cool with him, too. Worse, every collaboration with Kelly helped funneled money into the bank account of a man who has allegedly continued his abuse for at least 26 years and shows no signs of stopping.

We should have raised a stink about artists who collaborate with Kelly a long time ago; some of us, including journalists like DeRogatis and Jamilah Lemieux, have. But news cycles cycle on, outrage dims, and momentum stalls. Each new allegation or reentry of an old one into public discourse offers music consumers another opportunity to ask artists why they participated in the music industry’s cover-up for Kelly and why they haven’t, as a booster of his career, condemned his actions. There is no statute of limitations on the crime of enriching an alleged child rapist. By coming out against him late in the game, these artists still have an opportunity to publicize his pattern of victimization and get their fans to support an industry boycott of his work.

Celebrities already use their public platforms for advocacy against sexual predators all the time. Lady Gaga, who’s spoken publicly about being sexually assaulted when she was 19 by a man 20 years her senior, made an earnest, graphic music video about sexual assault for her song “Til It Happens to You” in 2015, depicting survivors with messages like “BELIEVE ME” scrawled on their bodies. She invited 50 survivors of sexual assault onstage with her to perform the song at last year’s Oscars. Of her friend Kesha, who accused producer Dr. Luke of years of emotional and sexual abuse, Gaga has said, “I feel like she’s being very publicly shamed for something that happens in the music industry all the time, to women and men. I just want to stand by her side because I can’t watch another woman that went through what I’ve been through suffer.”

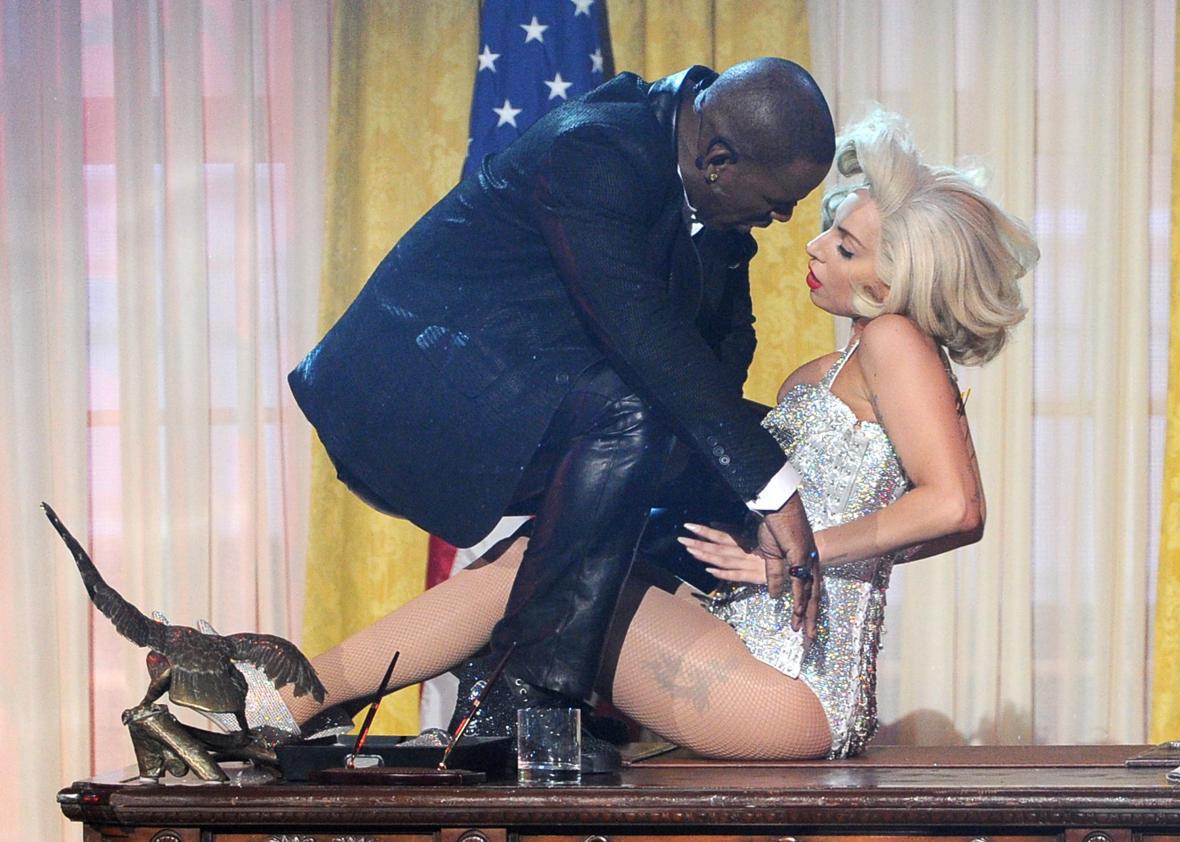

Yet Gaga made “Do What U Want” with Kelly in 2013, mimed fellatio with him onstage at the American Music Awards, then pulled the already-taped video for the song due to growing allegations against Kelly and director Terry Richardson. (Yes, Gaga made a video with two alleged sexual abusers for a song that advises the listener to “do what you want with my body.”) Gaga blamed her team and her tight schedule for a video she says she didn’t like and didn’t want to release, but other sources claimed that Gaga thought the highly sexual video wouldn’t play well after DeRogatis’ reporting on Kelly resurfaced in December 2013 and reports of Richardson’s alleged harassment came out in early 2014. Instead of addressing the allegations against Richardson and Kelly and taking an ethical stance, Gaga spun her scrapping of the video as a move of artistic self-editing.

In other industries, we expect major players to defend or end their personal and financial connections to bad actors almost as a matter of policy. Dozens of companies pulled their ads from Bill O’Reilly’s show after the New York Times revealed that Fox News had paid $13 million to settle five separate sexual harassment claims against him. Lately, when women come out with stories of discrimination and harassment in the tech industry, big names in the field are pressed to speak up, even if they’re not directly involved. (Venture capitalist Chris Sacca recently bragged about doing just that—tweeting support for Ellen Pao after she lost her discrimination suit against Kleiner Perkins—in a post about his own role in Silicon Valley’s mistreatment of women.) But in the entertainment industry, with a few major exceptions like the singular case of Bill Cosby, celebrities are usually forgiven their connections to abusers, even as they help those abusers appear harmless and amass wealth.

The recent example of Kesha and Dr. Luke provides useful contrast to the nonreaction of music stars to Kelly’s documented history of sexually manipulating teen girls. Taylor Swift publicly donated $250,000 to Kesha for her legal battle against her alleged abuser, a well-known pop producer. Miley Cyrus and Kelly Clarkson, both of whom had worked with Dr. Luke in the past, also came out with public statements to put themselves on Kesha’s side. Adele, the biggest recording artist on Sony, which owned the Dr. Luke’s Kesha-producing label, made a statement in support of Kesha while accepting a BRIT award last year. Sony happens to be R. Kelly’s label, too, but Adele isn’t saying a peep about him. His alleged victims are far more numerous than Dr. Luke’s, as far as the general public knows, but they aren’t famous and, crucially, it seems most of them aren’t white. In a Colorlines piece published this week, Lemieux writes that Kelly’s continued career success is indicative of “the idea that black men are more in need of protection than black women.” Research has shown, she continues, that “black girls are widely perceived as being older or more mature than they actually are, which helps to explain the number of people who don’t see teenage girls who have sexual relationships with men like Kelly as victims, even when they are legally unable to consent.” The women who’ve charged Kelly with rape, assault, and abuse have to watch their alleged assailant make millions off his music because his colleagues have kept mum and recorded with him in spite of his history.

Pushing for Kelly’s former collaborators to renounce him works in two ways: First, it pressures individual artists to stop enriching him and supporting his public profile. It also sends a clear message to unaffiliated observers that the swell of public opinion is falling against Kelly, and they’d be better off not booking him in their arena, hosting him on their talk shows, or inviting him to do a guest spot on a new track. True, it would be sad if DeRogatis’ most recent revelations in BuzzFeed (nearly the only allegations of abuse against Kelly that involve women above the age of consent) were the thing that finally convinced Kelly’s one-time associates to speak out against him. But you know what they say about apologizing for lining the pockets of alleged child rapists—better do it late than never. When some next set of accusations lands on Kelly, as it almost certainly will, Gaga the survivor’s advocate will be glad she did.