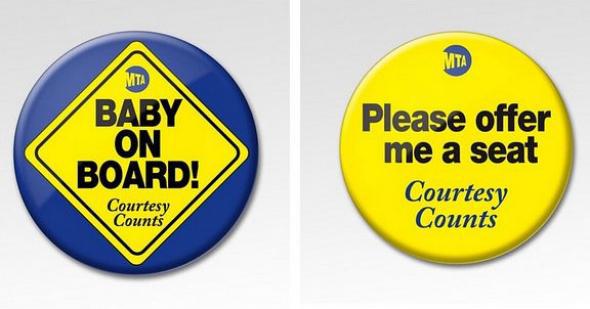

While our federal government is still trying to decide whether pregnancy should count as a pre-existing condition, New York City, at least, is taking a small step toward improving the lives of pregnant women: The city’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the organization that oversees the subway system, plans to start handing out “Baby on Board” buttons for pregnant riders to wear and silently signify that they’d like a seat, please.

Though you wouldn’t know it from the aforementioned health care conversation, being pregnant takes a physical toll on women’s bodies: They deal with fatigue, swelling, and all manner of bodily discomforts that go along with carrying so much more weight than they’re used to. So yes, their need to sit is more pressing than that of most of the rest of the people on the train. The same is true of the elderly and/or disabled, who will get MTA buttons of their own with a more general “Please Offer Me a Seat” message.

The agency’s politeness campaign—it previously tackled the scourge of “manspreading”—may seem like a funny thing to focus on in the midst of the “rapidly deteriorating” subway system crisis, but hey, it’s a nice thought, and we should all be so lucky as to have a transportation authority that can do both.

Whether the buttons idea will actually get more pregnant butts in seats is a tougher call. As Jezebel put it, the buttons “[suggest] that what’s really coming between seats and the people who need them isn’t simple obtuseness, but an abundance of caution.” The MTA thinks New Yorkers are too polite to risk implying that someone looks pregnant/disabled/old, marking the first time in history New Yorkers have been accused of being overly deferential. The buttons don’t address other, more likely, potential reasons behind not offering seats, such as inattention (many subway riders are on their phone or reading, with their ears protected by headphones, not scanning the crowd for people who look like they could use a seat) or flat-out selfishness (other subway riders just don’t care: first come, first served).

So what’s a pregnant woman who wants to take a load off between the Bronx and Battery Park to do? By all means, try your button. Wear it proudly, and try to angle your chest especially in the direction of the rude and oblivious people taking up all the seats in your car. But when that doesn’t work, here’s a novel idea: Why not try asking?

Slate women who have ridden subways while pregnant report that asking for a seat feels awkward. (As pop psychology tells us, asking for what you want often does.) Talking to a stranger on a subway at all is a departure from the norm, but it’s bound to feel even weirder when your goal is to get something, even if that thing, a seat, is free, and you deserve it. And how do you decide who to ask among the benches full of people, each one more uninterested than the next? In the 1970s, a social experiment sought to study how people reacted to being asked to give up their subway seats, but one of its main findings turned out to be that the experimenters found it incredibly difficult to ask in the first place.

What’s the worst that could happen? You get a no, a dirty look? When women (and old people, and disabled people) don’t feel comfortable asking for what they need, the rest of the world is more than happy to erase them. There are already too many forces in the universe that don’t want to support women, the elderly, and the disabled—it’s the whole impulse behind the belief that not every one deserves health care. Asking for a seat is one way to fight against this, to stop acting like it’s fair for needy people to suffer in service of some misunderstanding of fairness and equality. People who don’t fall into the seat-needer categories can, in addition to getting up when the situation requires it, always help by supporting the seat-needers through shame and subtle bullying tactics against less-sensitive riders. It takes a village.

The MTA hasn’t totally solved this let-them-have-seats problem with its buttons—ignoring a button is just as easy as ignoring a cane or a protruding belly, and asking someone to move his or her butt so I can plop mine down instead will always be hard. But being able to point to a button by way of explanation does provide some additional ammunition for those seeking seats. At the very least, it’s a thing to point to while you start to clear your throat and gather up your courage to say something. Until the MTA endows pregnant women with remote controls that allow them to forcibly eject other riders from seats, that may be the best we can hope for.