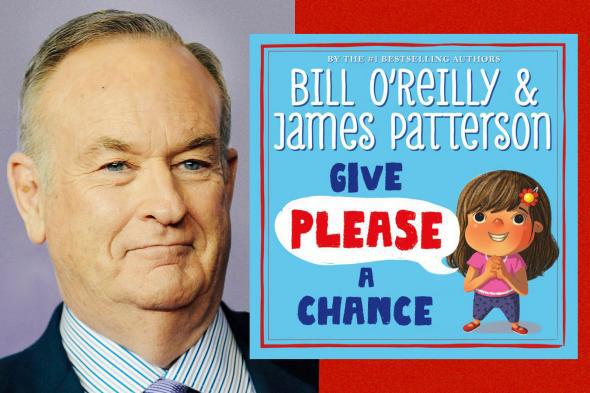

Bill O’Reilly’s latest children’s book, Give Please a Chance, is a deeply creepy artifact. In this book, co-credited to the prolific thriller writer James Patterson, children with Keane-ishly big eyes dangle from swings, gaze longingly at kittens through shop windows, or crave cookies. On the left-hand page of each spread, they beg for some object of desire; on the right-hand page, they suppress their wishes long enough to ask permission, using the “magic word.” In this book, even the kids who are actually in pain or trouble—one girl dangles, at a loss, from a rock-climbing wall, and another holds out a hand, asking “Daddy” to “make the splinter go away”—are enjoined to remember their “pleases” in asking for adult help.

The idea of Bill O’Reilly dispensing advice on politeness is hilarious. This is the man who refined “shut up” into an art form, foisted himself upon his female coworkers (okay, allegedly), and loves a good tantrum. Given the author’s record, the pedantry of Give Please a Chance is profoundly hypocritical, sure. But we can learn something important about O’Reilly’s appeal from that hypocrisy. The disconnect between his own actions and the behavior he and his coauthor expect is a relic of patriarchy, where “etiquette” and social mores constrain some people more than others.

O’Reilly’s advice for children is framed as generational wisdom. His brief preface to Give Please performs what Justin Peters identifies as the classic O’Reilly trick, framing one man’s perspective as only “common sense.” O’Reilly was a boy, once, he reminisces: “Life was much easier in those days because there were rules most Americans followed. Holding the door for someone. A nod and a hello. Even just saying ‘please.’ Most kids did those things back then, but now there is confusion in many places.” In an earlier advice book, The O’Reilly Factor for Kids (2004), the host also tapped his childhood experience in counseling kids to compromise and ask nicely. (“The more polite you are, the more responsive the other person will be. Remember that in any debate.”)

Lots of children’s literature is pedantic, bordering on manipulative. (As a new parent, I have recently acquired many, many pieces of propaganda on the virtues of sleep, designed to get baby to pass out so I can go watch the NBA playoffs in peace.) But O’Reilly’s advice books specifically teach children the virtue of submission. In a 2016 review of Give Please a Chance, Josh David Stein put it well: “What’s latent in the pages of Give Please a Chance isn’t politesse. It’s a societal framework where those who have less power are forced to beg from those who [have more].” O’Reilly’s authoritarian “advice” for children and his harassment of women are not unrelated. Both are products of a worldview in which power rules, and inconvenient people without power should learn blandishments in order to get along.

A person who, like O’Reilly and his older, whiter, maler viewership, remembers when his life was eased by the polite subservience of women, children, and minorities might well think back on those times with longing. Why do some people who should know better excuse Donald Trump’s bad behavior? Because in the patriarchy, Dad is allowed to be a jerk. For everyone else, the sugary-cute pages of Give Please a Chance offer a manual for behavior: Feel free to ask Dad for what you want or need—as long as you say the magic word.