On Monday, the State Department informed the Senate that the Trump administration would cut all U.S. funding to UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund, which received about $69 million from the U.S. last year and more than $75 million in 2015. This cut will create a major obstacle to the work of UNFPA, the U.N.’s primary supporter of contraceptive access, safe childbirth, gender-based violence response, and advocacy against abusive practices like child marriage and female genital mutilation around the world. With a presence in more than 150 countries, many of which get no direct U.S. aid, UNFPA is one of the largest contributors to the health and rights of women on the planet.

The action came via the Trump administration’s interpretation of the Kemp-Kasten Amendment, a rider that prohibits U.S. funding of any organization that “support[s] or participate[s] in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization.” The amendment has been added to appropriations legislation every year since 1985. Since then, every Republican administration has used it to cut U.S. funding from UNFPA. Every Democratic administration has reinterpreted the amendment to restore UNFPA funding.

Founded in part with a large U.S. donation in 1969, UNFPA is the only organization that has ever been affected by this amendment. Right-wing lawmakers have argued that UNFPA’s presence in China means it helps enforce China’s now-relaxed one-child policy through coercive means. This is not true. A State Department investigation commissioned by George W. Bush found “no evidence that UNFPA has supported or participated in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization in China.” Bush defunded the agency anyway. And in spite of the broad successes UNFPA-funded programs have seen in areas with some of the worst indicators of women’s health, the Trump administration is doing the same.

At present, the U.S. is the world’s second-largest donor to UNFPA’s humanitarian work, bringing maternal health services and post-sexual violence care to women in some of the most punishing crisis zones in the world. UNFPA runs the only maternity ward for pregnant Syrian refugee women who’ve crossed the border into Jordan, at the notorious Za’atari refugee camp, which has become a near-permanent home for some. U.S. funds given to UNFPA currently make up half the clinic’s operating budget, allowing it to deliver more than 7,000 babies without one maternal death. The U.S. also supports a UNFPA-founded “survivors’ center” in Duhok, Iraq—the primary location for support for girls and women who’ve been raped, sexually abused, and imprisoned by members of ISIS.

UNFPA is an integral driver of health and empowerment for girls and women outside of crisis zones, too. In Guatemala, for instance, the agency helps fund several NGOs that provide health care, contraception access, and education. The country has exhibited particular need in the past few years, since USAID shifted much of its health funding away from Latin America and toward Africa and South Asia. (Now, its aid to Latin America mostly focuses on violence and poverty—issues that cause people to migrate to the U.S.) Though average rates of maternal mortality, child marriage, and teen pregnancy have seen some improvement in the past two decades in Guatemala, they’re still some of the worst in the region; and indigenous people, who make up more than 40 percent of the country’s population, might as well live in a completely different country.

Indigenous mothers are more than two and a half times more likely to die during childbirth. Sixty-six percent of indigenous children are chronically malnourished, nearly twice the rate of non-indigenous children. Forty percent of indigenous adolescent girls get married before they’re 18, nearly twice the rate of non-indigenous girls, and more than half of indigenous girls will have a child before they turn 20. The number of pregnancies among girls aged 10 to 14—a demographic not even measured in many reports—is disturbingly high (more than 4,000 give birth each year) and has risen in recent years.

With funding from UNFPA and other donors, a group called Abriendo Oportunidades (“Opening Opportunities”) has been working to show that targeted peer education can help close some of these gaps. The organization, founded in 2004 with a $100,000 UNFPA grant and run by the reproductive-health research nonprofit Population Council, hires young indigenous women in rural areas (called “mentors”) to teach girls aged 8-18 in their communities about their bodies and sexual and reproductive rights. I met with some of these mentors in March, and many told me they’d never had any education on menstruation, sexual violence, or preventing unwanted pregnancies until they joined Abriendo Oportunidades in their early 20s and learned the curriculum they’d be teaching adolescent girls in their towns.

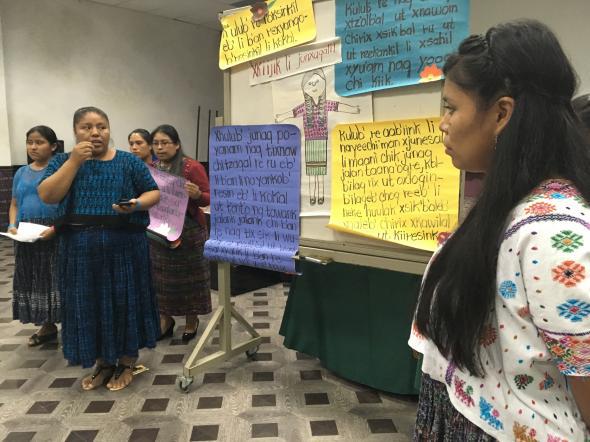

One of these women, Elizabeth, started as an intern with Abriendo Oportunidades several years ago and now works as a site coordinator in the department of Sololá, where she oversees 20 mentors and 800 girl students. “These girls have been overlooked, forgotten by the state,” she said. “They are girls who have limited access to schooling. They’re girls who don’t really know when their rights are being violated. Girls who, when they’re 12, 13 years of age, they run the risk of getting pregnant.” Sixty-nine percent of indigenous girls are illiterate, and in many of the communities where Abriendo Oportunidades works, few people speak Spanish, exacerbating existing barriers to education access. Mentors teach girls in their own indigenous languages, including K’iche’ and Kakchiquel, and sometimes learn new ones to broaden their reach.

When Abriendo Oportunidades mentors have their first interactions with the adolescents in their classes, they often have to counter common myths. Menstruation is thought to be an illness or sign of impending death, and most girls don’t know it means they could get pregnant, because their mothers and aunts never got that information either. Many believe babies arrive by stork delivery. One mentor told me that right off the bat, girls usually ask if she has any kids. When she says no, their eyes widen—some have never met a woman over 20 who wasn’t a mother.

Elvira Cuc Choc, 24, had never left her home community before joining Abriendo Oportunidades as a mentor. During her initial trainings, she learned that she didn’t know the proper names for genitalia: A vulva was a tamale or güisquil; penises were bananas or snails. Now she travels to other towns teaching girls that their body is their casa, their neighbor’s body is their neighbor’s casa, and no one has the right to enter another’s casa without permission. “It’s so important for girls,” she said. “By knowing their body they can prevent sexual violence. By knowing about reproductive issues, they can decide how many children they want to have, and also not become pregnant at an early age so they can continue studying.”

Christina Cauterucci

Another mentor, Elva Maria Tzoc Che, 26, said it was her “life’s dream to help girls and women,” so she was excited to answer a radio ad from Abriendo Oportunidades. She remembers learning the curriculum about dating, relationships, and partners who might try to pressure their girlfriends into sex. “Men I was dated were always asking for ‘proof of love’ and I didn’t know what they meant by that,” Tzoc Che told me. “It was hard for me, and I can relate to the young girls who have no information. … When I continued in the program, I realized it was my right to turn him down and say ‘no.’” Some of her former mentees still ask her for advice every now and then—when one recently got married, she called Tzoc Che to help recommend a family-planning method.

Population Council research has demonstrated the impact of Abriendo Oportunidades, which has reached 14,000 girls in hundreds of Guatemalan communities. A 2007 assessment found that girls given leadership roles in the program were 12 points more likely to finish sixth grade and 19 points more likely to avoid pregnancy than the national average. This success comes despite its already lean budget—in 2012, the total cost per girl per hour of education was $1.02—and any cuts will have an immediate impact on its reach and efficacy. “It is too early to know what exact effects the funding cuts will have for the thousands of girls who participate in Abriendo Oportunidades program,” Paola Broll, an Abriendo Oportunidades program officer said in a statement. “However, what is clear is that decision to pull support from the UNFPA jeopardizes many life-saving and life-improving programs like Abriendo Oportunidades for vulnerable girls and women in Guatemala and around the world.”

“If the Population Council no longer receives funding from UNFPA due to these cuts,” she continued, “Abriendo Oportunidades will need to significantly reduce its implementation or seek supplemental funding in a disadvantaged environment.”

The State Department’s memo on cutting UNFPA funding promised that the tens of millions of dollars that would have gone to UNFPA will go toward other “global health programs” the U.S. funds. But cutting funding from existing, successful programs will at the very least cause a disruption in service to women and girls who rely on UNFPA programs for critical care in times of need. Dozens of governments and NGOs not directly funded by UNFPA still rely on its heavily-discounted contraception procurement services to provide modern products to patients within their tight budgets. And there are many places and people that other organizations without UNFPA’s longevity, connections, and large-scale programs just don’t reach.

Delivering the babies of refugee women in Jordan, providing culturally competent care to rape victims of Boko Haram and ISIS—these are not services you can provide on a whim. Seema Jalan, executive director of the Universal Access Project (an organization that supports U.N.-aligned reproductive health initiatives), says programs like this can’t easily be taken over by another NGO. “That takes a lot of infrastructure, a lot of expertise, that UNFPA is uniquely qualified to provide,” she said in a press call on Tuesday. “This can’t be a game of chess.”