Uber is staging a major PR defense for the second time in recent weeks after a former employee published a detailed account of persistent sexual harassment and discrimination she allegedly faced while working as an engineer at the company. Susan Fowler, who left the company in December after about a year of employment, claims in her Feb. 19 blog post that her manager sent her sexual chat messages soon after she was hired. When she reported him to human resources, she writes, she was told that it was his “first offense” and that she should switch teams if she didn’t want a negative performance review from him. Fowler later found out that other women had reported witnessing inappropriate behavior from this same man, and each were told that it was his “first offense” and not a big enough deal to require action.

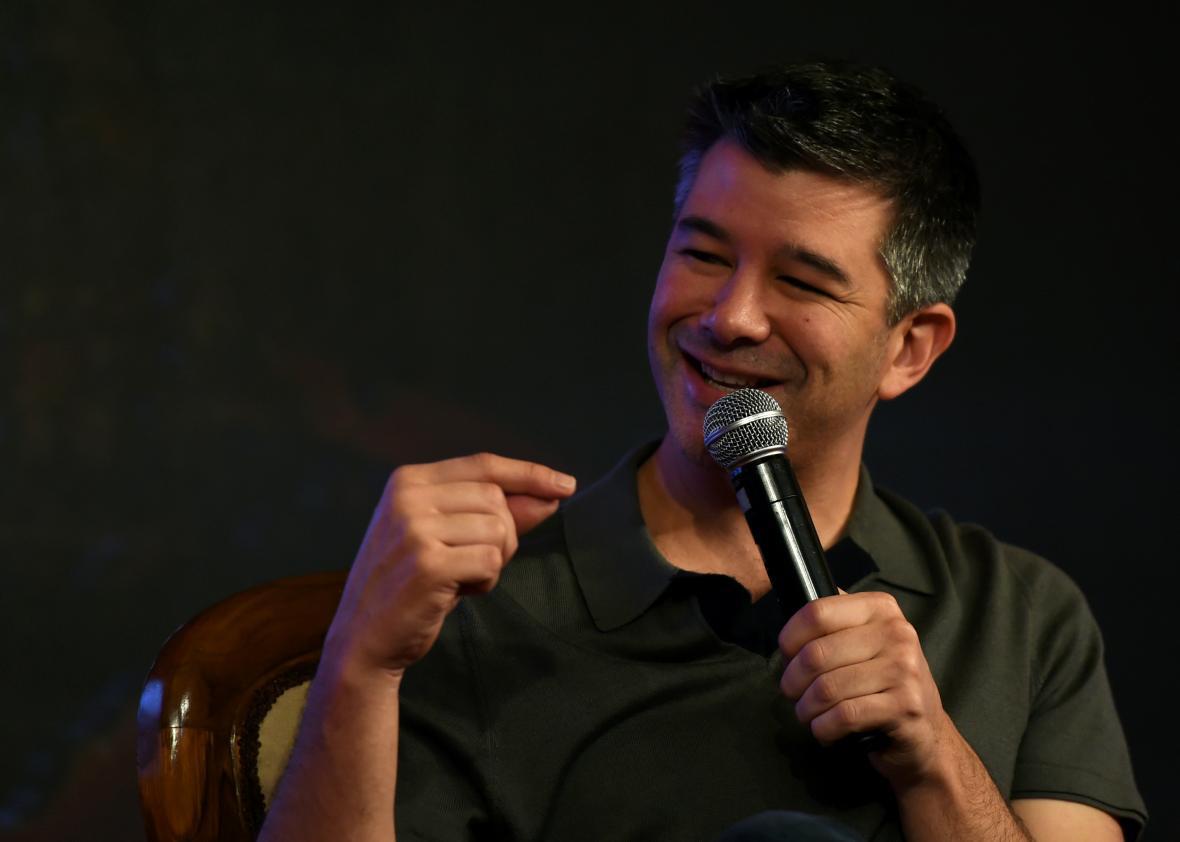

Fowler’s story, which gets even more convoluted, is an alarming reminder that there are many overlapping reasons why tech companies often have a meager population of women on staff. Uber CEO Travis Kalanick revealed in a memo to employees on Monday that the company employs just 15 percent women in its technical roles. (For comparison, Google reports that 19 percent of its tech workforce is female, Airbnb reports 26 percent, and Twitter is even with Uber at 15 percent.) The gender gap in tech starts with teachers and toymakers discouraging girls from pursuing STEM interests. It’s cemented by structural biases that find female MIT graduates earning far less than their male peers in a larger wage gap than alumni of any other elite university. And it’s justified by the president of the United States’ closest advisor, who advanced the misogynist fairytale of women having an innate intellectual deficiency in math.

But there’s another, more egregious barrier to women entering and succeeding in the tech sector: the industry itself. A 2009 report from the National Center for Women & Information Technology noted that women left tech careers at a “staggering” rate. While 74 percent of women in tech said they were “loving their work,” the industry had a 56 percent attrition rate among women within 10 years—a higher rate than both science and engineering, and about twice as high as the attrition rate for men. In 2015, a Stack Overflow survey of 26,000 programmers found that 92.1 percent identified themselves as male. Software engineer Kate Heddleston came up with an instructive analogy that explains the inadequacies of current efforts to get more women into the tech pipeline:

Women in tech are the canary in the coal mine. Normally when the canary in the coal mine starts dying you know the environment is toxic and you should get the hell out. Instead, the tech industry is looking at the canary, wondering why it can’t breathe, saying “Lean in, canary. Lean in!” When one canary dies they get a new one because getting more canaries is how you fix the lack of canaries, right? Except the problem is that there isn’t enough oxygen in the coal mine, not that there are too few canaries.

Tech’s gender gap is a problem in and of itself, but it should be seen as a symptom of an industry that’s rewarded hostility to women. When women see Apple forcing a woman’s face to smile to demonstrate a new photo-editing feature, hear a Microsoft CEO telling women to stop asking for raises so they have better “karma,” and notice the sexually humiliating environments created at tech conferences, they wonder whether a career in tech is worth years of listening to men joke about the size of their “dongles.” When they learn that 60 percent of women in tech say they’ve been sexually harassed in the workplace, the tradeoff seems even less appealing. It’s widely known that women sometimes leave tech companies because they encounter hostile work environments or, as in Fowler’s case, because they’re denied promotions or fired for reporting inappropriate behavior. It is much harder to measure how many women don’t pursue programming jobs in the first place because they anticipate male-dominated workplaces that foster demeaning, discriminatory behavior.

In her blog post, Fowler accuses a manager of changing her performance scores after a stellar review to keep her from getting a transfer to another team, because it reflected well on the manager to prove he could retain female engineers on his team. This is a particularly outrageous deed in an account full of outrageous deeds. Instead of enforcing a zero-tolerance sexual-harassment policy or asking female employees how management could better support them, Uber has allegedly moved to improve its substandard track record on gender by narrowing opportunities for women on staff and sweeping harassment allegations under the floor mat. Fowler writes that she made repeated, documented human resources complaints about the unfair treatment she endured, but she was gaslighted by an HR representative who told her the emails she sent never happened and that men are better suited for certain jobs than women. It took a statement on a public blog to get any action from company leadership. A current Uber employee would never be able to take that kind of risk. More likely, she’d suffer in silence as long as she could stand it, then quietly leave the industry, marked by a small percentage shift on Uber’s gender data report.