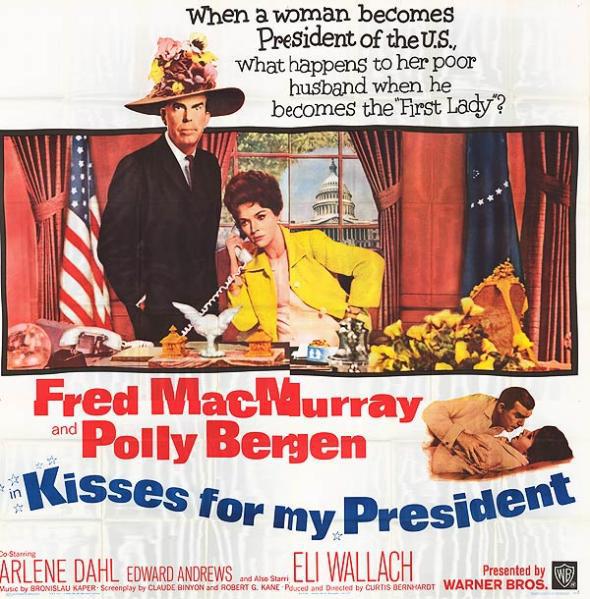

Before the concept of a woman winning the American presidency became a real possibility, it was fodder for popular entertainment. In 1964, Kisses for My President arrived in theaters, receiving middling to negative reviews. It was the first American movie to depict a woman winning the White House, and, now that Warner Brothers has made it available for rental on YouTube, it’s a fascinating and possibly instructive document to revisit as America faces the real thing.

In the film, Fred MacMurray, then at the peak of his film and television career, plays Thad McCloud, the president’s husband (the starring role), while Polly Bergen plays Leslie McCloud, the nation’s first woman president. The film begins with her inauguration, and we learn that forty million women enthusiastically embraced her candidacy. How and why is unclear. Today, it’s worth noting that we may be about to witness something similar: Hillary has opened up the largest gender gap in the polls ever recorded, and married, college-educated white women, long a Republican group, appear likely to turn out for her. When the dust settles after Nov. 8, I wonder what we’ll learn about one of the issues that Kisses pushes off-screen: differences of opinion between married women voters and their husbands over how they may have voted.

Picking up on another trope that has surrounded Clinton, Kisses emphasizes the male subordination wrought by a female president through Leslie’s husband Thad. Before his wife reached for power, Thad was an entrepreneur who owned an electronics company with significant government contracts. He sold the firm upon his wife’s election to avoid conflicts of interest, and thus now has little to do—a situation the film presents as equal parts worrisome and comical. We Americans are used to having First Ladies; indeed, their inaugural ball gowns fill the most popular gallery in the National Museum of American History. But the prospect of a “first man” remains something alien. After 1920, when a constitutional amendment gave women the vote—at least outside the Jim Crow South, where black women’s voting rights were still denied—discussions of the idea of a woman president often focused on the outlandish consequence of a man holding the traditionally ceremonial, feminized role.

In numerous belabored, unfunny scenes, First Gentleman Thad contemplates the feminine décor in his office and bedroom. White House staffers press him to choose the menu for meals and deal with the couple’s two bratty children, tasks that require wifely skills that he lacks. Of course, some real-life First Ladies have stretched the role to take on unusual duties, notably Eleanor Roosevelt and Clinton herself. Michelle Obama has become an icon of strong African American women and remains one of the nation’s most popular public figures. What Bill Clinton would do with the position remains unclear—but, in a worryingly macho move, we do know he already submitted Hillary’s old cookie recipe in place of an original one.

While Thad is wringing his hands over domestic concerns, President McCloud is preoccupied with affairs of state—which we know because we repeatedly see her husband trying to initiate intimacy with her, only to have her called away by phone calls from cabinet members reporting crises. Thus we see again how political ambition in women continues today to desexualize them, calling to mind a thousand sexist tropes about frigidity and Hillary’s pantsuits. Meanwhile, an old flame of Mr. McCloud’s has appeared: one Doris Weaver (Arlene Dahl), who, naturally, had been President McCloud’s roommate at Radcliffe back in the day. Doris now owns a chain of beauty salons as well as a line of cosmetics. She sees that Mr. McCloud is unfulfilled and unhappy. “Do I detect a wounded male ego?” she asks. “Not wounded, deceased,” he replies. She offers him a job as vice president of the men’s cologne division of her company. He realizes he must decline: “If I take the job, I’ll have two presidents,” he says.

The rest of the plot, such as it is, consists of warmed-over early Cold War motifs, which play out to exceedingly sexist conclusions. Naturally, the hero of the movie, the one who saves the country from the machinations of a Latin American dictator named Valdez, is not Leslie McCloud, but Thad—who first punches out Valdez in a bar brawl, and then offers skillful hearing testimony exposing that Walsh, a corrupt senator, is secretly doing Valdez’s bidding. The unmistakable message, of course, is that Thad is the brains behind the president.

To be fair, there is one element in the film that was considered progressive at the time. One of the few interesting sequences shows the newly inaugurated Madam President shaking hands with the White House kitchen and domestic staff, who are African American. News reports indicate that some interpreted this scene as an example of a success resulting from an NAACP-led campaign in 1963 to increase the availability to black actors of roles as extras in Hollywood pictures, as well as to improve their pay relative to their white counterparts.

But from today’s standpoint, Kisses cannot help but look wretchedly old-fashioned. In an absurdly abrupt, deus ex machina conclusion, the moviemakers invoke yet another sexist premise—apparently the only way out of the mess that female ambition has made. President McCloud faints, a scare which is followed immediately by the announcement by her press secretary that “The President is pregnant.” She resigns, since her doctors have told her that she must either give up her strenuous position or else lose the baby. And as the movie closes, her husband reminds her that although it took forty million women to get her into office, it only took one man to get her out, thus proving the natural superiority of his sex.

Kisses for My President is at once a relic of a time thankfully long gone, and a reminder of the deeply ingrained sexist assumptions that we still carry around in our heads and we may take with us into the privacy of the voting booth. Ambitious women will surely recognize, in its interminable scenes, some of the impossible double binds in which they have been placed. And even while female voters’ motivations are left out of the film’s narrative frame, its opening scene—the sounds of women chanting “Leslie!” as Mrs. McCloud places her hand on a Bible to utter the oath of office—is nonetheless a powerful reminder of how many millions of American women and girls have hoped to see such a vision, perhaps one day soon.