When the novelist Lionel Shriver delivered her now-notorious speech about cultural appropriation at the Brisbane Writer’s Festival last month, it wasn’t clear whether she was wrestling with a real intellectual menace or a straw man. Censorious identity politics, she argued, are potentially suffocating to literary inspiration, since authors fear that creating characters from marginalized backgrounds will invite charges of cultural pillaging. Shriver, who is white, described a “climate of super-sensitivity, giving rise to proliferating prohibitions supposedly in the interest of social justice that constrain fiction writers and prospectively makes our work impossible.” She delivered these remarks while wearing a sombrero.

The outraged response to Shriver’s speech, from festival organizers as well as onlookers, seemed to confirm her point. (“Lionel Shriver’s Address on Cultural Appropriation Roils a Writers Conference,” said the New York Times headline.) Yet the speech itself was short on examples of writers being hounded for borrowing from other cultures. (“So far, the majority of these farcical cases of ‘appropriation’ have concentrated on fashion, dance, and music,” she said.) Shriver quoted a prissy review published “out of San Francisco” of Chris Cleave’s 2009 novel Little Bee, a book by a white man written from the perspective of a teenage Nigerian girl.

Mostly, though, Shriver appeared indignant about criticism of her own work, including a Washington Post review that called out “racist characterizations” in her latest novel, The Mandibles. Indeed, it is dicey for a white writer to depict a white family leading an uncontrollable African-American woman around on a leash, as Shriver does in that book. It’s not dicey enough, however, to preclude invitations to deliver keynote addresses at international literary conferences. In other words, it’s hard to see who is enforcing the “proliferating prohibitions” Shriver describes.

All the same, inhibition is subjective; if writers feel inhibited, they are. The white novelist Jess Row wrote a penetrating critique of Shriver in the New Republic: “Shriver’s ‘crisis,’ in any demonstrable, concrete sense, is a fantasy—a powerful, successful artist’s bad dream, in which some faceless censor, or critic, or angry brown-skinned person, is going to come and take everything she has away.” Yet Row himself notes, almost as an aside, that his agent urged him against writing his novel Your Face In Mine, in which a character undergoes “racial reassignment surgery,” due to the political backlash it would invite. Due to a combination of culturally ascendant left-wing politics and the roving shame squads of social media, at least some people feel like they need to watch what they say. And anxiety about tripping over taboos isn’t great for literature.

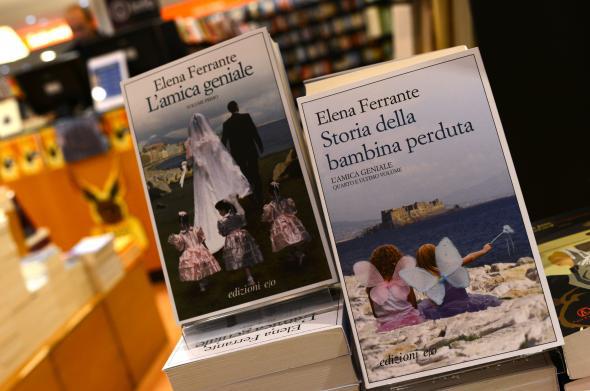

This is why I’m pleased to see the outing of Elena Ferrante being met with such protective indignation on behalf of the beloved author, even though it now seems that she didn’t come from the desperate milieu that forms the background to her famous novels. As you surely know by now, the New York Review of Books, in concert with French, German and Italian publications, has published Claudio Gatti’s exposé of the real identity of Ferrante, who wrote the four novels known as the Neapolitan Quartet under a pseudonym. Ferrante is also the author of a book of purportedly autobiographical miscellanea titled Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey, which will be released in the United States in November. In that book, Ferrante suggests that she shares the poor Neapolitan background of Elena and Lila, the characters whose friendship is at the core of her four-book epic, though she also coyly warns the reader that she might be lying to shield herself.

Gatti, a literal-minded investigative journalist, yanks away the veil of mystery Ferrante has created. “Far from the daughter of a Neapolitan seamstress described in Frantumaglia, new revelations from real estate and financial records point to Anita Raja, a Rome-based translator whose German-born mother fled the Holocaust and later married a Neapolitan magistrate,” he writes. He has revealed Ferrante as a middle-class Jewish woman, not a child of gang-ridden slums. An accompanying article about Raja’s family background begins, “There are no traces of Anita Raja’s personal history in Elena Ferrante’s fiction.” Ferrante has taken the details of a distant subaltern world and turned them into novels that feel viscerally real.

In other words, as Adam Kirsch writes in the New York Times, it “appears that one of the world’s best-loved writers is actually a sterling example of the power of appropriation.” The response to this revelation has been fury—not at Ferrante’s obfuscation, but at Gatti’s invasion of her privacy. “For Literary World, Unmasking Elena Ferrante is Not a Scoop. It’s a Disgrace,” says an NPR headline. In The New Yorker, Alexandra Schwartz derides Gatti as a self-righteous philistine. “He, not Ferrante, seems to be the fictional persona, a puffed-up pedant straight out of Nabokov, right down to his Nabokovian name: Claudio the Cat, prowling around in search of secrets,” Schwartz writes. “Gatti is the kind of reader who sees ‘clues’ in a writer’s work, as if she has constructed a puzzle to be solved rather than written a novel to be read.”

In the reaction to Ferrante’s unmasking, we have a spontaneous, impassioned affirmation that the value of fiction is independent of the identity of its creator. Shriver’s fear that jejune objections to cultural appropriation would filter into literary criticism turns out to be, if not groundless, then overblown. Readers and writers alike still have a deep-rooted belief in the right of artists to venture beyond the fences of their own privilege, as long as the art itself justifies it.