A new algorithm could revolutionize the way police process rape kits, making sense of fragmented DNA evidence that previously left human analysts stumped, according to the science and tech website Vocativ. “It’s a little bit like this amorphous, magical unicorn thing,” Kristi Lanzisera, a supervising criminalist in the Alameda County Sheriff’s forensic biology unit, said of the software. “Everybody is either in the process of purchasing or plans to purchase and will purchase it in the future.”

Criminalists have high hopes for the new technology because the laborious process of testing rape kits has contributed to a notorious backlog. Best estimates suggest that hundreds of thousands of kits—which contain the forensic evidence collected, through an often-invasive physical exam, after a woman reports a rape—are languishing in storage all over the country. Some have been there for decades; untold others have been destroyed untested. Now, a process called probabilistic genotyping may be able to do in minutes what previously took hours of careful work. The Vocativ story explains why extracting usable evidence from rape kits can be such a time-consuming endeavor:

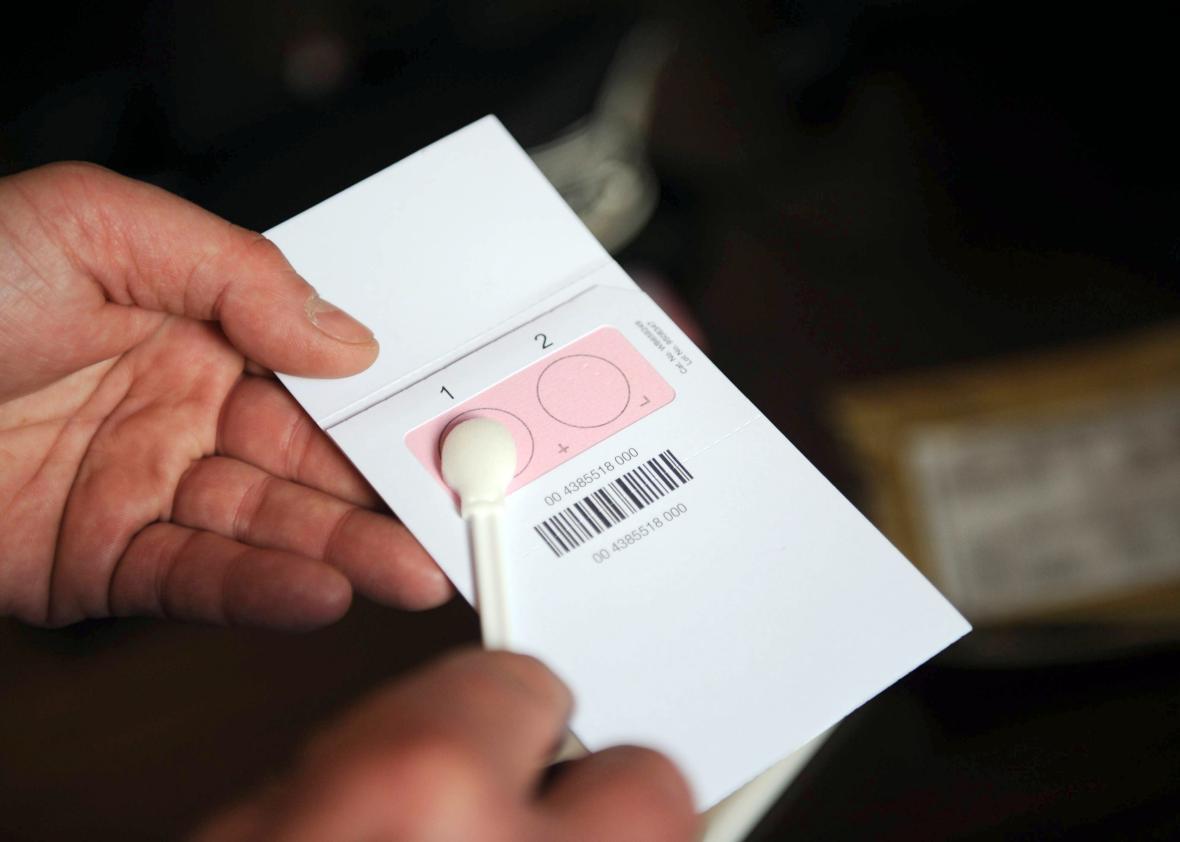

Rape kits often contain samples with both the victim’s DNA, as well as that of at least one perpetrator. These are known as mixtures and they’re incredibly difficult to analyze. In identifying a genotype, analysts typically compare variations, or alleles, on 13 points in the DNA. But when there are multiple people’s DNA involved in a sample, it can be difficult to tell which alleles belong together or, put another way, to the same person. Probabilistic genotyping software performs complex mathematical computations—much faster and with greater accuracy than a human can—of the statistical likelihood of the individual genotypes in a mixture.

As police departments begin adopting the new genotyping software, politicians are making their own efforts to address the rape kit backlog. Vice President Joe Biden raised the issue’s profile in 2014, when he proposed that the White House put $35 million into testing kits. (Since processing costs between $1,000 and $1,500 per kit, and the Department of Justice estimated that around 400,000 kits remained untested nationwide in 2014, the total budget needed to eliminate the problem would likely have exceeded $500,000,000.) Just this month, Congress unanimously passed a “bill of rights” for survivors of sexual assault, which gives women more control over the fate of their kits. President Obama is expected to sign the bill, which would provide free forensic exams to all victims (in some states, women are still expected to pay out of pocket), and would guarantee that labs must inform victims of any results. The bill also mandates that rape kits be preserved for 20 years or the duration of the statute of limitations, and gives victims the option of a notification before the kit is destroyed, and the ability to extend its time in storage.

Innovations in rape kit testing matter because, as my colleague Christina Cauterucci has written, “Rape kit–testing initiatives in cities around the country have proven that prompt processing can identify serial rapists and prevent them from committing further crimes.” For example:

After New York City began testing every rape kit that came into police custody, the city’s rape arrest rate rose from 40 percent to 70 percent. With the help of advocates like local businesswomen and Erykah Badu, Detroit has nearly eliminated its 11,341-kit backlog from 2009, identifying 652 potential serial rapists along the way. A new analysis out this week projects that Cleveland’s effort to clear its backlog will yield nearly 1,000 new convictions; the researchers “conservatively” estimate that 25 percent of rapists go on to rape again if they’re not convicted after their first crime.

Though some states have vowed to eliminate their backlogs, Vocativ reports that technological advances could, paradoxically, delay the achievement of that goal. With the software, “evidence that was previously discarded as uninterpretable is now giving positive or negative results, that is implicating or exonerating an accused [person] or being suitable for upload to a database,” John Buckleton, the co-creator of a probabilistic genotyping program called STRMix, told Vocativ. That could create more work for the overburdened, underfunded labs devoted to processing the kits—but it could also send more rapists to jail, and give more victims the comfort of seeing justice served.