In photos from last Thursday’s amfAR gala at Cannes, it might look like auction host Uma Thurman wasn’t perturbed by the surprise open-mouthed kiss she fielded from “playboy industrialist” and Fiat heir Lapo Elkann. With a gracious smile, she stood for the cameras as he pressed his sweaty face against hers and dangled his lit cigarette dangerously close to her updo.

Elkann, who formerly worked as the head of marketing for Fiat and a personal assistant to Henry Kissinger, had placed the winning $196,000 bid for two tickets to the Victoria’s Secret fashion show.* When he posed for a series of celebratory photos with Thurman, he went in for the kiss.

Those pictures belie the reality of the situation: As Thurman’s rep later made clear, the kiss was “not consensual.” “It is opportunism at its worst. She wasn’t complicit in it,” Thurman’s rep said in a statement. “Somewhere in his head [Elkann] must have thought it an appropriate way of behaving. It clearly wasn’t. She is very unhappy that this happened to her and feels violated.”

Elkann’s behavior springs from the prevalent belief that while an unwanted kiss might be uncomfortable, it’s ultimately benign; that since it doesn’t involve sex organs or any body part usually covered by clothing, it’s not a form of sexual assault; that it’s OK to take the kiss first and ask permission later. Elkann’s actions were also informed by the idea that celebrities owe the public some intimate part of themselves, a notion furthered by the routine obligation for celebrities (especially women and people of color) to remain composed and courteous in front of the cameras or risk embarrassing the company that hired them and coming off as frigid, angry, ungrateful divas.

Another famous product of the intersecting cultures of celebrity and rape: the surprise kiss Adrien Brody planted on Halle Berry at the 2003 Oscars. When he stepped onstage to accept the Best Actor award for his work in The Pianist, Brody overtook Berry—whose arms were open for the customary congratulatory hug and cheek smooch—by dipping her into a full-on kiss. “I bet they didn’t tell you that was in the gift bag,” he began, as if she’d be crazy to object to an unexpected wet one foisted upon her in front of an audience of millions. “It’s obvious from the tension in Berry’s closed eyes … and the way she sort of disgustedly wipes her face as he begins his speech that the incident wasn’t pre-planned or welcome,” wrote Stacia L. Brown at PostBourgie in 2008. “I’m still left wondering, even after all these years, why there wasn’t more controversy or fall-out surrounding this moment.”

Indeed, the general response to Brody’s forced makeout was one of amazed admiration. USA Today published Susan Wloszczyna’s weak-kneed homage to the “swooningly smooth” nonconsensual kiss, quoting a romance novelist who quipped, “Women want a man to sweep them off their feet, and isn’t it wonderful that PC notions can’t change that universal feeling.” Wloszczyna herself wondered, “Who could blame women for wondering in unison, through tears and smiles, ‘Who is that guy?’ ”

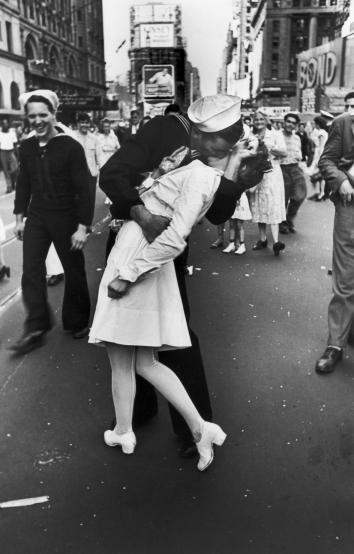

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Pix Inc./Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

The surprise stranger kiss–as–romantic gesture has roots as American as “V-J Day in Times Square,” the iconic photo of a World War II sailor smooching a nurse that’s found its way onto generations of college dorm posters. It’s long been hailed as the epitomic image of patriotic romance, though a 2005 interview with the nurse, Greta Friedman, revealed that it was more akin to a sexual assault. “Suddenly, I was grabbed by a sailor. … I did not observe anybody taking pictures. I was anxious to get back to work,” she recalled, calling herself a “bystander” to the incident. “It wasn’t my choice to be kissed. … The guy just came over and grabbed.”

Though Friedman was not a celebrity, her situation bears similarities to Thurman’s and Berry’s. Her body language—her limp left arm, contorted right arm, and tight fist—is visibly tense and uncomfortable, like Berry’s. The sailor exerts his physical will on her by clutching her face, like Brody grabbed Berry’s, and like Elkann seized the back of Thurman’s head with both hands. The world reacted to “V-J Day in Times Square” with sentimentalism; the audience at the 2003 Oscars and the after-the-fact media critics applauded Brody’s bold display of joy and lust, barely, if ever, stopping to question whether Berry enjoyed it—and even if she did, whether Brody ever gained her consent before putting his lips on her face. The other sailor in “V-J Day” laughs at the spectacle of his compatriot snatching an unsuspecting woman on the street; Jack Nicholson and Nicolas Cage, whom Brody beat out for the 2003 Oscar, cheered Brody’s crass behavior with glee.

Giphy

The kiss Elkann forced on Thurman has aroused far more controversy than the one Brody foisted upon Berry. This can be explained by four social phenomena. For one, over the past couple of years, mainstream media has engaged in far broader and deeper conversations around rape culture, which likely gave Thurman more leeway to voice her anger and more traction once publications got word. There’s also a nascent celebrity trend of speaking out against haters and violators, making space for feel-good narratives of women taking agency over their own bodies and images. The fury for Thurman that Berry never saw is indicative of an imaginary hierarchy of sexual assault, which says that Brody is handsome, talented, and swoon-worthy, so Berry should count herself lucky to be on the receiving end of his saliva. (On the other hand, since no one’s swooning over Elkann, Thurman seems more justified in her protests.) Berry, the only woman of color to ever win a Best Actress award, also faces more and stricter barriers to raising a fuss over a public violation of her body than the white Thurman.

But the most disheartening part of these images is that the women remain composed and gracious, keeping the focus on their respective events, even as their bodily autonomy is invaded. Thurman went along with Elkann’s too-close hug at first. After Brody grabbed and kissed her, Berry turned around with a good-natured laugh, as in, “This guy! What a stud!” Thurman’s characterization, “opportunism at its worst,” is apt. Elkann, Brody, and the “V-J Day” sailor took the risk of forcing a kiss on an unsuspecting woman in places where they knew they’d face at least temporary impunity: a charity gala, an awards show, a bustling public square brimming with patriotic zeal, a space in front of the camera’s watchful eye, where women would be unlikely to scream or sock them. And the audience clapped.

Correction, May 24, 2016: This post originally stated that Elkann worked as the CEO of Fiat. He was not the CEO; he was the head of marketing.