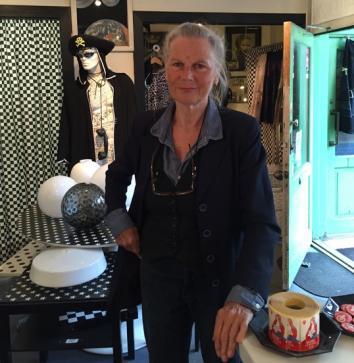

There is a radical feminist thrift store in Denmark run by the former art director of Cosmopolitan magazine. I learned this by accident. Taking a break from Women Deliver, a massive international women’s health conference taking place in Copenhagen, I went wandering down Gothersgade Street and stumbled into a basement shop selling junky furniture, old feminist propaganda posters, shirts silkscreened with a clenched first inside the Venus symbol, and a small bowl decorated with Emma Goldman’s face. Presiding over it all was a striking 72-year-old woman named Lin van Roe, who I soon discovered used to be known as Lene Bernbom, back when she designed Cosmo for Helen Gurley Brown.

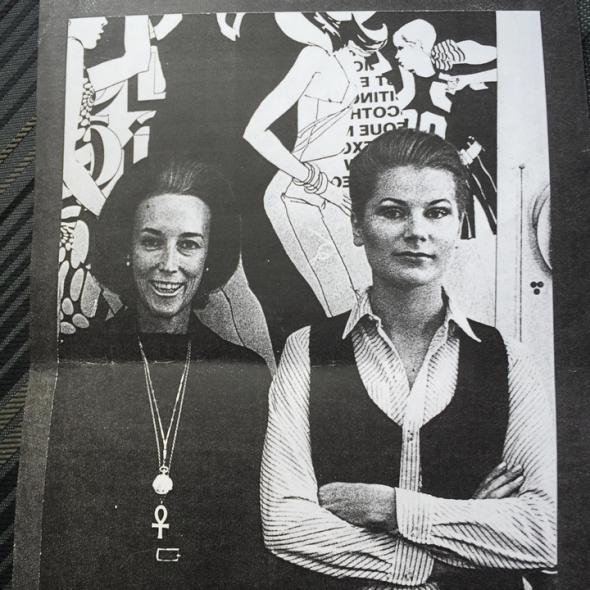

Van Roe left Denmark for the U.S. when she was 19 and joined the pioneering women’s magazine in 1966, when she was 22. As much of a product of its era as Playboy, Cosmo urged women to liberate themselves from the sexual strictures of the times—to have affairs and cultivate their libidos—even as it instructed them on submitting to regressive gender norms. If “you’re not a sex object, you’re in trouble,” Gurley Brown once said.

Van Roe found her domain at once freeing and oppressive. Gurley Brown, she says, was like a mother to her, but she often disagreed with her boss’s vision. “She kept asking, ‘Why don’t you put a pair of big tits on the cover?’ ” van Roe recalls. “I thought, Why make it vulgar?” She and Gurley Brown sometimes had screaming matches in the office. “Helen was famous for not raising her voice,” says Brooke Hauser, author of the new book Enter Helen: The Invention of Helen Gurley Brown and the Rise of the Modern Single Woman. “Lene was the only person who could get her to raise her voice.”

In 1970, a group of feminists picketed Cosmo, demanding $15,000 in “reparations,” a monthly feminist column, and an “immediate end to sexist advertising and articles which perpetuate the image of women as sexual conveniences for men.” Van Roe, who at the time could have passed for one of the magazine’s models, says the feminists yelled at her for conforming to sexist beauty standards. She was hurt, but she also felt they had a point about her industry. “That’s why I got out of it,” she says. “I thought they were right.”

Michelle Goldberg

Being pretty, she says, never brought her much joy. “Sure, now I look good—so what?” she says of her younger self. “It didn’t make me any happier. If I had been a young man, I could go down to the Russian Tea Room, which was very close to the office, and have a drink at night. Sit at the bar and have a drink. But you couldn’t do that, because then you were a hooker! Right away some asshole would come up.” A few moments later, she adds, “Everybody wanted a blow job. I got so tired of men.”

But the beauty imperative isn’t so easily waved away, and van Roe felt its pressure even as she disdained it. She describes herself as plagued by 5 kilograms (about 11 pounds) she couldn’t lose. It didn’t help that she was in an environment that fetishized thinness. “Helen Gurley Brown is famous for encouraging women to be skinny,” Hauser says. Hauser’s book describes a dinner Gurley Brown once served to a Cosmo writer: a single shared hard-boiled egg, lettuce, and a dressing of mineral oil—a laxative.

Van Roe developed an eating disorder. “I’d go out at night to the drug store and buy a box of chocolate and ask them to gift-wrap it,” she says. “And then buy two yogurts.” At home, she’d tear the paper off and devour the candies until there were only a couple left. Then, overcome with regret, she’d go downstairs and throw them into the incinerator.

Eventually, van Roe visited a doctor recommended to her by a male model. At her first appointment, she says, the entire cast of Hair was in the waiting room. The doctor started her on a series of shots, a combination of B12 and amphetamines. She was also smoking a lot of pot. She got thin but also started to crack up.

Her crisis came to a head in the Côte d’Azur, where she was sent to do a story about traveling the French Riviera on a budget. Seized with a sense that she had to get away, she rented a Volkswagen and drove back to Denmark. Her parents weren’t sure what to make of it when their daughter, the big American success, showed up at their door. “They didn’t know what a nervous breakdown was,” she says.

A journey into new age spirituality and a long but ultimately failed marriage to an alcoholic followed. Then, in 1990, she walked into Kvindehuset, the women’s house, a sort of feminist cultural center. It published a small magazine, hosted a counseling service, and organized annual women-only camping trips that still take place. At the time, the community was at war over lesbian separatism; all were suspicious of the elegant woman who wanted to join them. “It was pretty tough to come in here with all these concrete feminists, the heavy duty lesbians, and here I was with lipstick,” says van Roe.

But she was drawn to feminism and kept coming back to Kvindehuset, eventually taking over the basement thrift store. Twenty-five years ago she married a woman. Van Roe started printing feminist T-shirts and teaching girls from underprivileged backgrounds about fashion design. Hauser tried to track her down when she was working on Enter Helen, but she has a new name and no email address, and it seemed as if she’d disappeared. Van Roe still lives on the money she made at Cosmo, which she says was invested wisely by the alcoholic.

She says she’s finally found peace. “For me, in this house here, with all these young women, all these young feminists, it’s wonderful,” she says. “I’m happy here.”