This week, the U.S. Treasury announced that Harriet Tubman will replace Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill. For some, this is an act of revolutionary change. It is a momentous action for a nation that supported slavery for close to 300 years (including the colonial era) and freedom for half that. To recognize the life of a formally enslaved woman on federal currency is a significant statement.

However, for some, placing Tubman on American greenbacks is an extension of the commodification of enslaved people and a slap in the face to her legacy. “I don’t want to see Tubman commodified with a price, as she once was as a slave,” wrote the Guardian’s Steven W. Thrasher last summer. “It’s clear that putting her face on America’s currency would undermine her legacy,” declared Feminista Jones in the Washington Post. How should we evaluate these arguments in a moment where so many relics of the past are being removed, revised, rewritten, and relocated?

As a scholar of American slavery and someone who’s published books and taught courses on black women in America for nearly twenty years, I can’t separate my feelings about Tubman’s ascension to the $20 from the historical context. First, Tubman: Most Americans know her story (or parts of it), and she is often one of the few enslaved women people can name. She is an icon and a figure who facilitated revolutionary change. Born into slavery and relegated as property, Tubman defied the commodification of her personhood by liberating herself and many others. Because of her vast knowledge of the geography and topography of several states, she served as a scout for the Union Army during the Civil War. Her story is one of perseverance, of bravery, of survival, and it highlights the importance of liberty.

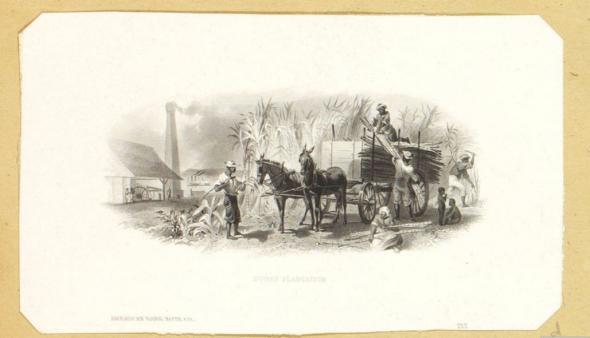

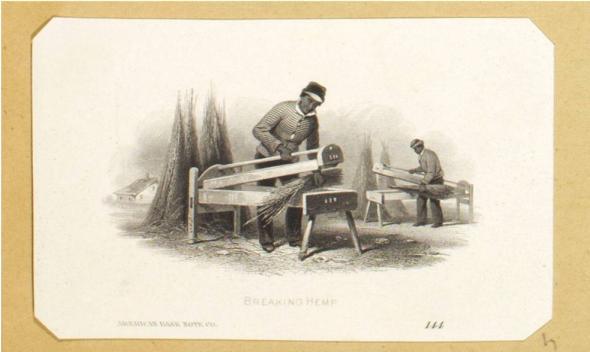

Harriet Tubman will be the first African American (male or female) to appear on federally sanctioned currency, but she is not the first enslaved person to appear on paper money circulated in the United States. Before the 1860s, it was common for banks to issue their own notes embellished with images that served as anti-counterfeit devices. Several bills printed in Confederate states during the Civil War featured sketches of enslaved people. These images depict enslaved people in captivity with plantation tools and crops in their hands. The American Bank Note Company and Bald, Cousland & Company also issued a series of vignettes intended for print currency that contained scenes of draymen and field hands breaking hemp, hauling sugar cane, tapping sap from large trees, and picking cotton. The original engravings remain at the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Library of Congress, but we cannot tell if they ever appeared on any bank notes. It’s likely these particular vignettes did not—but the fact that the images were created in the first place indicates how central slavery was to America’s identity in the 19th century.

Library Company of Philadelphia

Library Company of Philadelphia

Since the announcement that Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson—along with other major overhauls to the $5, $10, and $20 bills—colleagues, students, family, and friends have expressed concerns about the (mis)appropriation of Tubman, some claiming that her exploitation has extended beyond the grave. Is Tubman’s postmortem appearance on the $20 comparable to the exploitative images of anonymous enslaved people on Confederate currency? Or will the new $20 find a new way of depicting black bodies on money—one that is empowering rather than degrading?

In my forthcoming book about black bodies and postmortem commodification, I argue that even when black bodies were relegated to property, black people saw themselves as human beings and expressed their humanity by any means possible, including geographical movement. Along these lines, and in the context of the Tubman announcement, the life of a formerly enslaved woman named Nanny is particularly instructive. Nanny of Jamaica was a self-liberated runaway who led a community of maroons—fugitives who escaped slavery and lived in some form of isolation—to fight against the British in the First Maroon War from 1720 to 1739. On more than one occasion she used guerilla warfare to claim territory in Blue Mountains. She is one of Jamaica’s national heroes, and she is the first Jamaican woman to appear a widely circulated bill, the $500 bill.

What do Tubman and Nanny have in common? Simply put, revolutionary movement. Both liberated themselves and helped others acquire freedom. They defied opposition and operated undercover, traveling through remote and uninhabited places. They were freedom fighters and they risked their lives to liberate others. Their faces on contemporary currency are wildly different from the anonymous enslaved bodies found on Confederate currency. The images on Confederate bills celebrated the institution of slavery; Tubman’s and Nanny’s bills celebrate individuals who fought against it.

Putting these women on currency is a fitting tribute to their revolutionary movement. Just as Tubman and Nanny moved, so does currency. It crosses county lines, state boundaries, even national borders, enabling payments and purchases that can in themselves be acts of independence and self-determination. Soon Tubman will be on federally regulated banknotes in circulation. Rather than interpret this as an act of commodification, this is a commemoration that is long overdue. To be sure, Tubman is not on the bill for sale—rather, like Nanny, she will be on the bill that facilitates it.