Under a wave of criticism over its planned inclusion of artifacts related to Bill Cosby in an upcoming exhibition about black entertainers, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture has reversed an earlier claim that it would present the items without reference to Cosby’s alleged history of sexual assault.

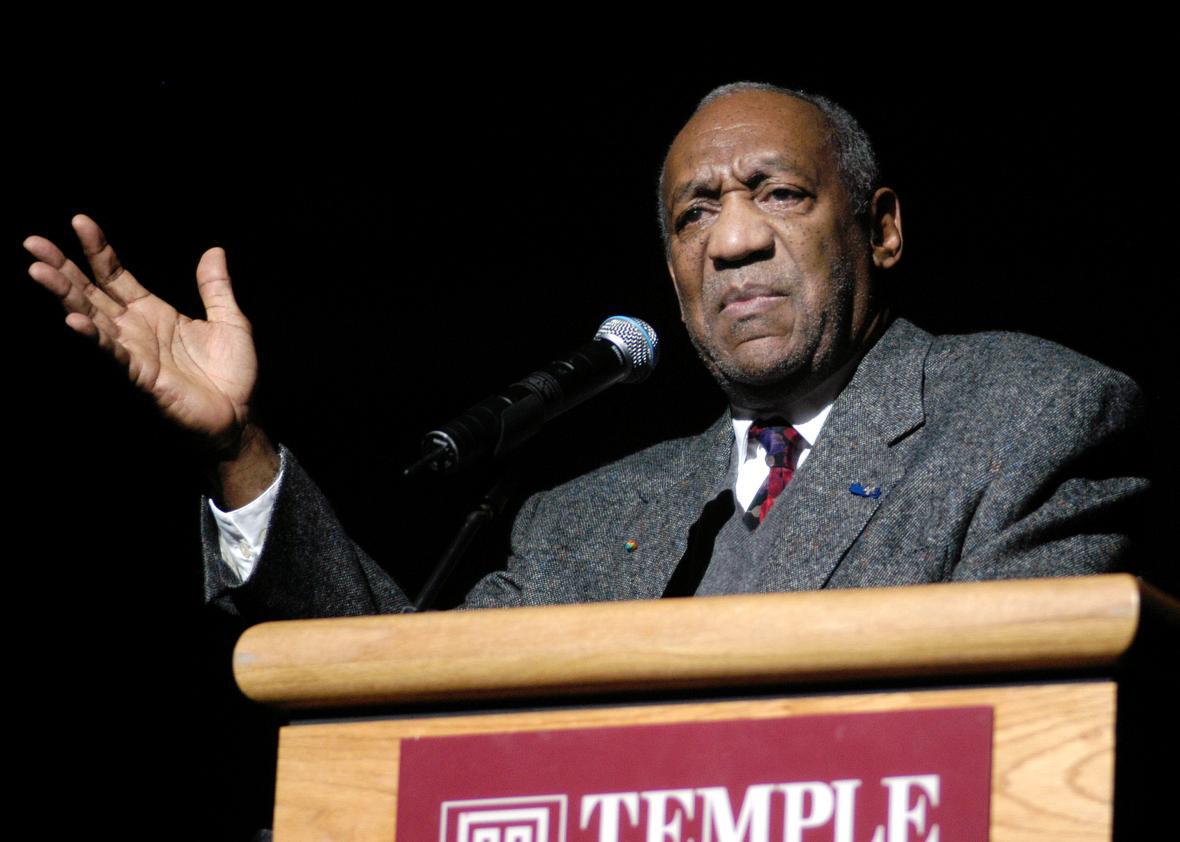

A March 27 New York Times preview of the museum, which is set to open in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 24, reported that the exhibit would showcase one of Cosby’s comedy records, a comic book related to his TV show I Spy, and videos of I Spy and The Cosby Show. “Curators said they wanted Cosby’s place in history to stand alone without their mentioning the current allegations,” Graham Bowley wrote, quoting a curator who identified Cosby as perhaps the most important African-American figure in 20th-century television.

In the days following that report, women who’ve accused Cosby of sexual abuse denounced the museum’s painting-over of an inconvenient turn in the comedian’s popular image as a squeaky clean—moralizing, even—family man. The museum defended its decision. “There is not a Bill Cosby exhibition,” it said in a statement on Twitter. “The museum explores a diverse and complex history that reflects how all Americans are shaped by the African American experience.” A Smithsonian spokeswoman confirmed to the Washington Post that the text accompanying the Cosby artifacts would not address the dozens of sexual assault allegations leveled against him, some of which are still progressing through the courts.

On Thursday, the NMAAHC’s founding director, Lonnie Bunch, released a statement countering that party line. “Like all of history, our interpretation of Bill Cosby is a work in progress, something that will continue to evolve as new evidence and insights come to the fore,” he wrote. “Visitors will leave the exhibition knowing more about Mr. Cosby’s impact on American entertainment, while recognizing that his legacy has been severely damaged by the recent accusations.”

The statement said some observers have recommended that the museum dump any reference to Cosby, lest it blindly applaud an alleged serial rapist or give the impression that the Smithsonian condones his alleged crimes. “We understand but respectfully disagree” with that suggestion, Bunch wrote. “For too long, aspects of African American history have been erased and undervalued, creating an incomplete interpretation of the American past. This museum seeks to tell, in the words of the eminent historian John Hope Franklin, ‘the unvarnished truth’ that will help our visitors to remember and better understand what has often been erased and forgotten.”

Bunch is right—the contributions of people of color have been underplayed and written out of every branch of historical study. In arts and culture in particular, white people have adopted and profited from black traditions for generations. But the lives of sexual assault survivors have been excised from popular histories, too, bolstering the legacies of men who abused their power at others’ expense. As Kriston Capps wrote in the Atlantic earlier this week, “This is how culture works to protect powerful alleged sexual predators.” It sounds like the museum was poised to varnish the truth, so to speak, by erasing the stories of more than 50 brave women who’ve come out against Cosby, many of whom are women of color. NMAAHC officials were smart to reconsider their impulse to make Cosby’s legitimate contribution to American culture the sole pillar of his legacy.

Bunch’s reversal also indicates that the Smithsonian may have learned a lesson from the outcry that accompanied its 15-month exhibition of Bill and Camille Cosby’s art collection at the National Museum of African Art. The show, which closed this January, opened in late 2014, just as discussions of the years-old allegations against Cosby gained new traction and several new women came out against him. The Cosbys, longtime friends of the museum’s director, Johnnetta Cole, had donated more than $700,000 to the museum. Back in 2014, Cole defended the exhibition as “fundamentally about the artworks and the artists who created them, not Mr. Cosby.”

Was it, though? The show included a quilt covered in images of Cosby and his family, a painting by his daughter, quotes attributed to Cosby on the gallery walls, and placards praising his commitment to African-American art. In a particularly tasteless move, the museum kept one of Cosby’s family quilts, made of old T-shirts, on display. It contained a square that read, “What part of no didn’t you understand?”

Several months after the show opened, the museum made a marginal concession to protesters by adding a tone-deaf sign at the entrance that seemed to blame anyone concerned about the allegations against Cosby for ruining a perfectly good exhibition. The country’s preoccupation with the comedian’s alleged sex crimes had, the sign read, “cast a negative light on what should be a joyful exploration of African and African American art.”

The case of the NMAAHC is both weightier than that of the African Art Museum, since it’s a permanent display, and less so, because the entire exhibition does not hinge on Cosby’s name. The museums’ equivocation speaks to the predicament of many African-American cultural institutions that are grappling with the prospect of Cosby as a fallen star. The Cosby Show was a treasured reflection of black life for people who rarely saw their families represented in popular media, and it both normalized and complicated white America’s understanding of the black upper-middle–class family. There is no doubt that Cosby was an influential force in American comedy and a groundbreaker for black actors and comedians—that’s why the revelations about his alleged history of sexual abuse have so completely shocked and appalled the country. Cosby should absolutely have a place in a museum of black history and culture. But if we are to do right by future generations who’ll interpret Cosby’s legacy from exhibitions like this one, it must not evade the complicated truths of his story.