The New York Times has been dominating the Hollywood diversity beat in the wake of #OscarsSoWhite—see, for instance, a recent feature analyzing the nature of the roles that have gotten black actors nominated for Oscars. (They typically involve incarceration, violence, and poverty—a sad reflection of how Hollywood honchos see black people.) Now, the Times has devoted considerable resources to an interactive featuring the personal anecdotes and observations of 27 Hollywood veterans—including actors, directors, screenwriters, producers, and a cinematographer—who aren’t straight white men. Think of it as an oral history of discrimination in modern Hollywood.

No one will be surprised that Hollywood is dominated by white men, but you might be surprised by just how incredibly boneheaded and callous those white men can be. The Times feature, drawn from a series of interviews by Melena Ryzik, is a collection of aggressions both macro- and micro-. Latino actors Eva Longoria, America Ferrara, and Jimmy Smits recall being told they don’t look or sound Latino enough or that there can’t be more than one Latino actor in a movie. Morgan Freeman’s producing partner remembers a studio head insisting that the actor couldn’t play the president of the United States in a sci-fi movie. Actor Wendell Pierce tells a story of stunning ignorance, when a casting director told him, “I couldn’t put you in a Shakespeare movie, because they didn’t have black people then.” Then Pierce outdoes himself with a tale of a network executive asking Gregory Hines whether black people kiss their kids. “That was the most offensive thing I think I’ve ever [heard],” Pierce adds.

Those last two anecdotes happened in the 1980s and 1990s—and since then, much has changed for the better. The increase in representational diversity over the past decade, on television in particular, has been well-documented. But the Times feature powerfully shows why improvements in onscreen diversity are not enough: Hollywood needs more women, people of color, and sexual minorities in leadership roles in all studios and departments. Many of the miscommunications, conflicts, and hurtful comments recounted in the Times interviews almost certainly wouldn’t have occurred if the upper echelons of Hollywood were more diverse. For instance, Julia Roberts recounts a frustrating conversation with the producers of Erin Brockovich about a scene that would have gratuitously sexualized her character:

I remember my first meeting with the producers on “Erin Brockovich,” before Steven Soderbergh came onto it, and saying, “This scene where she’s shimmying down a well in a micromini? I can’t do that.” [They said], “But that’s really what happened.” And I go, “I know, but once you make it a movie, you have to re-examine, what’s the function of this scene?” I didn’t feel I was being fully understood. People assumed it was about my sense of modesty. And you just think, “No, you’re not hearing what I’m saying.”

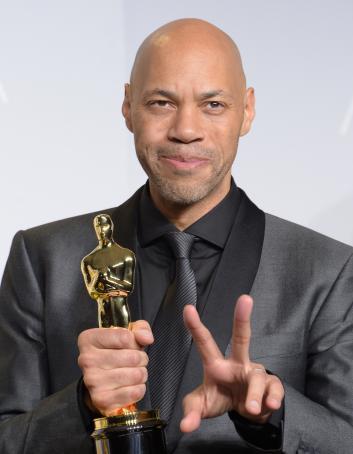

It’s unclear whether there were other women in the room during this conversation—Erin Brockovich’s production team was, unusually, equally split between men and women—but it’s hard to imagine a woman not hearing what Roberts was saying. Similarly, consider this dismissive comment made by an executive to 12 Years a Slave screenwriter John Ridley, which likely wouldn’t have happened if the executive worked with other black people:

[In a mid-1990s] meeting, it was determined the lead [for a film] would be a black woman, and I remember the executive saying, “Why does she have to be black?” And me saying: “She doesn’t have to be; I want her to be black. Why would you not consider it?” It was stunning that they were so comfortable [saying that] to a person of color. That was the most painful, that casual disregard for my experience.

Then there’s director Karyn Kusama, who discovered that even when women dominated the creative development of a movie, they still had to deal with a male-dominated, thoroughly sexist marketing department:

The marketing department wanted Megan [Fox, star of “Jennifer’s Body”] to do live chats with amateur porn sites, and I was like, “I’m begging you not to go to her with this idea, she will become so dispirited.” It was fascinating to have the writer be female, the director be female, the stars be female, and my head executive be female, and then we get to the top of the mountain, all those [male] marketing people. It was crushing.

More diversity in marketing departments, C-suites, and boardrooms won’t fix all of Hollywood’s problems. But it will forestall some of the flagrant discrimination that women and people of color in creative positions put up with today. And it will also make it more likely for stories by and about people who aren’t white men to make it onto the screen. “We don’t have enough people in the decision-making process,” actor and director Eva Longoria told the Times. Until that changes, movies and TV will never reflect what America really looks like.