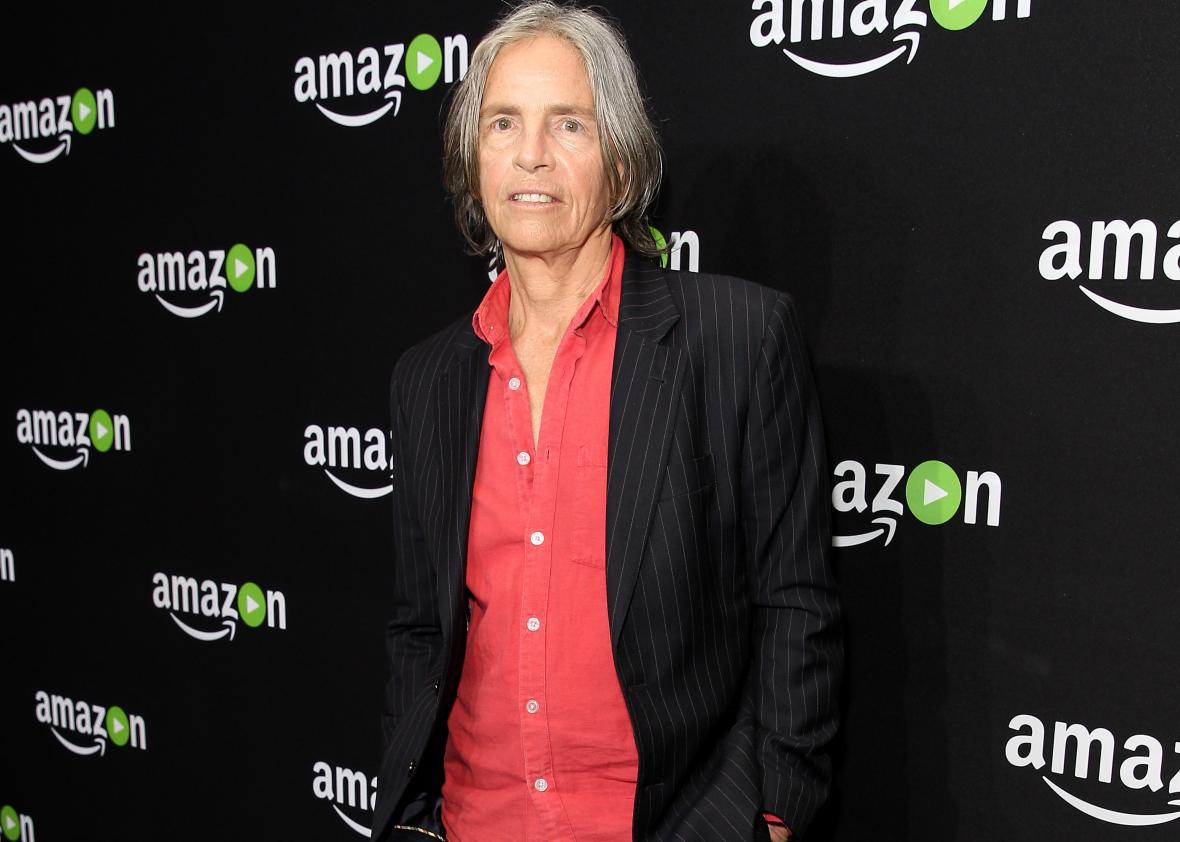

If there were any American feminist hearts yet uncaptured by Eileen Myles, today they were won. The acclaimed poet spoke with the New York Times’ Ana Marie Cox for the latter’s “Talk” column, and the resulting Q&A is just as edifying as anything you might expect from Myles, an unapologetic gender warrior.

The uninitiated and short on time need not read much past the interview’s exquisite, succinct headline, “Eileen Myles Wants Men to Take a Hike,” to get a sense of the artist’s general thrust. For of a more detailed primer on Myles’ career as a radical performer and one of the most artful, perceptive writers of our time, read on: The one-time presidential candidate offers a defense of poetry (“Poetry always, always, always is a key piece of democracy. … As things get worse, poetry gets better, because it becomes more necessary.”) and a sexual paradigm for the voting booth (“a dirty, ecstatic, alone moment, which is what every American deserves”).

When Myles ran for president in 1991 and 1992, she pegged herself as an “openly female candidate,” finding new ways to critique and find meaning in the tedious, increasingly grotesque quadrennial election spectacle. “This wasn’t a Deez Nutz-style stunt—it was an act of political protest,” Andrea K. Scott noted in the New Yorker. In 1995, Myles wrote that she was moved to campaign after learning that candidates did not write their own speeches, and thus were not speaking their minds, as she would do. “This year I would probably not say what was on my mind so you can see how from year to year a woman’s candidacy can change,” she went on. “It’s a flexible thing.”

Myles’ uninhibited musings on electoral politics offer a refreshing outsider’s take on a race that’s desensitized many habitual observers to its more ludicrous phenomena. “She’s probably as openly female as a Republican can be,” Myles told Cox of Carly Fiorina. “That party does not support the reality of a female in any way, so what does it mean to be a woman running under the banner of that party?” What unexpected pleasure to read such a perspective in the Grey Lady. “Eileen Myles Is the Only Good Pundit in America,” Jezebel proclaimed of Times piece. In her interview, Cox discovered that Myles had never heard Donald Trump’s campaign slogan before; when Cox enlightened her, Myles called it “so forgettable.” She also put forth her own proposal for Making America Great Again:

I think it would be a great time for men, basically, to go on vacation. There isn’t enough work for everybody. Certainly in the arts, in all genres, I think that men should step away. I think men should stop writing books. I think men should stop making movies or television. Say, for 50 to 100 years.

Myles’ brilliantly hyperbolic suggestion recognizes that even the smartest, best-intentioned efforts aimed at gender equity can only yield incremental change—and in the arts, only a profound shake-up could begin to compensate for the millennia of cultural erasure women have endured.

In addition to her exquisite poetry and novels, Myles has granted us some of the most nuanced explorations of gender available in mainstream media. In an interview for a New Yorker profile of Transparent showrunner Jill Soloway, with whom Myles constitutes a dreamboat power couple, Ariel Levy confronted Myles about people who use “they” as a singular gender-neutral pronoun. “I’m obsessed with that part in the Bible when Jesus is given the opportunity to cure a person possessed by demons,” she said. “And Jesus says, ‘What is your name?’ And the person replies, ‘My name is legion.’ Whatever is not normative is many.” The possibilities of gender, in other words, are as vast and manifold as the individuals who claim identities outside the norm need them to be.

Myles has illuminated the complexities of gender in her own life, too; she’s said that she felt like a boy as a child and prayed she’d grow into a man as she aged. Now, she told Levy, “I’m happy complicating what being a woman, a dyke, is. I’m the gender of Eileen.” During Myles’ recent Times interview, Cox tried to catch the poet in a binary bind: “You’ve said that if you were born 30 years later, you might have wound up transitioning to male. Yet you’ve written so much about femaleness and your love of vaginas. There are a lot of men who also love vaginas, but wouldn’t you miss yours?”

“Well, I think one can be more male and keep the vagina,” Myles countered. Despite all the popular fascination with the genital happenings of transgender or genderqueer people, trans identity is not defined nor limited by any individual body part. Myles is advancing a looser, freer conception of gender in the vein of Buck Angel, a trans man and porn superstar who’s thoroughly embraced his vagina and the pleasures it affords him, billing himself as the “man with a pussy.” That Myles has done this work in private and public, whether hyped or under-the-radar, for decades, is a commendable achievement. “Whoever falls in love with me is in trouble,” Myles once wrote, in a journal that nurtured Soloway’s crush on the poet. After reading today’s Times Q&A, I fear we’re all doomed.