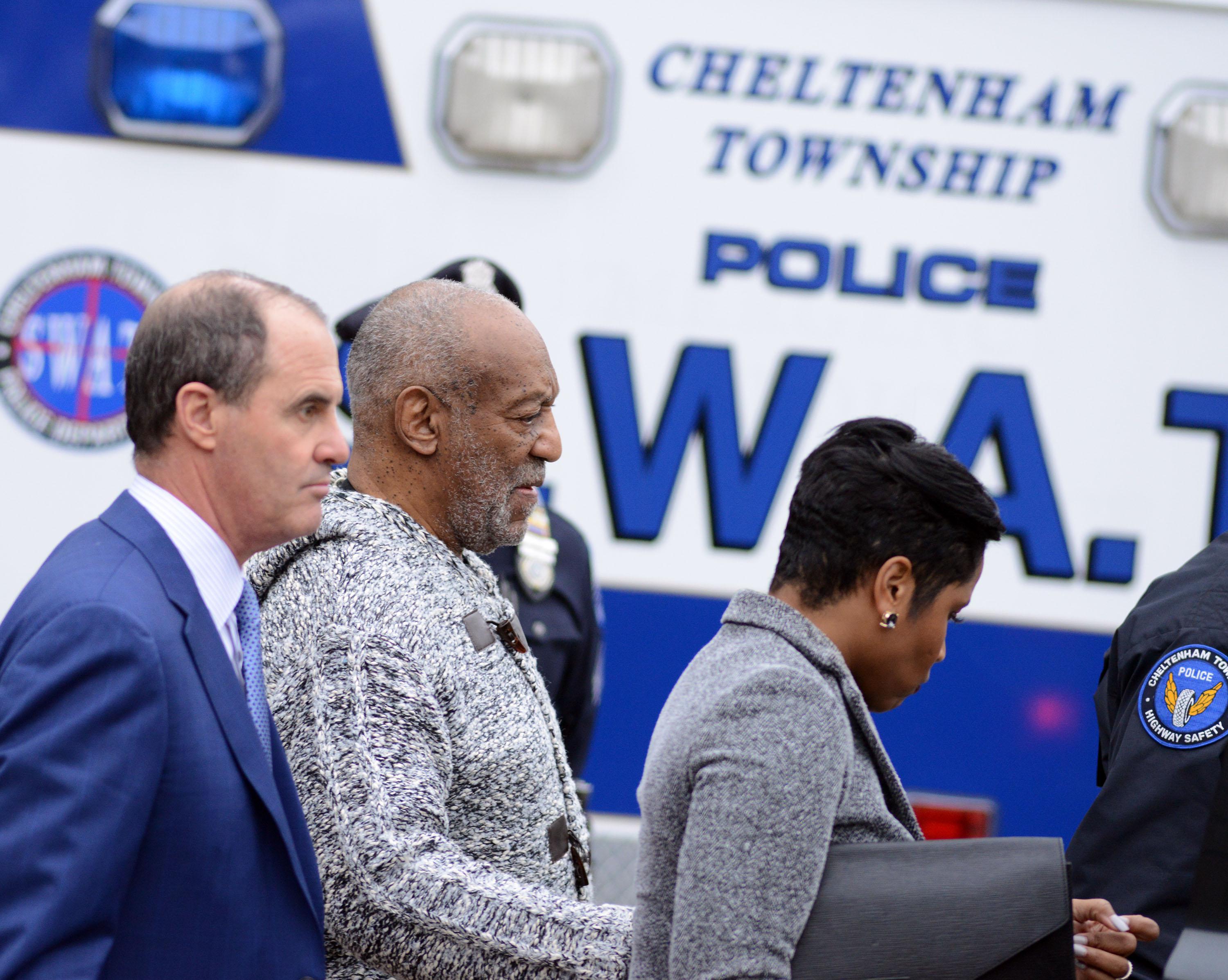

Yesterday’s filing of sexual assault charges against Bill Cosby provides a decent preview of what a trial would likely entail. According to the complaint, Cosby drugged his victim before fondling and digitally penetrating her. The woman, Andrea Constand, recalls that, shortly after consuming the drugs and alcohol, her legs became “rubbery” and “like jelly”; her vision became “blurry”; she felt “nauseous” and she was “in and out.” While Cosby was touching her, she was “frozen” and “paralyzed,” unable to move or speak.

The complaint also describes Cosby’s version of events. In a statement to police and later at a civil deposition, he admitted to providing Constand drugs (Benadryl, he told investigators). He also acknowledged engaging in the sex acts in question, but nevertheless claimed that Constand consented, since she never told him to stop or pushed him away.

Cosby’s fame, and the number of women who have come forward to relate similar experiences of victimization, make this case unusual. But the sexual assault of a person impaired by intoxicants is hardly uncommon. According to a 2010 survey published by the CDC, 8 percent of women in the U.S. haveexperienced alcohol or drug-facilitated sexual assault. These cases raise important questions about how the law defines rape.

More than half of U.S. states still define rape in terms of use of physical force. In these jurisdictions, an alleged victim’s lack of consent alone does not mean she was raped. (The Model Penal Code, which is designed to influence state legislatures, also falls into the “force required” category, although this may be changing.) Many states, including Massachusetts, Illinois, and California, expressly require force as an element of the crime, while others define rape as sex without consent, but then include force as a component of non-consent. In Pennsylvania, “aggravated indecent assault,” with which Cosby is charged, outlaws penetration without the complainant’s consent. But rape—the more serious crime involving sexual intercourse—does not include a similar provision. While intercourse with an unconscious person and intercourse after administering drugs to prevent resistance are both considered rape, as a general proposition, intercourse without consent is not. “Forcible compulsion,” it should be said, is defined more expansively in Pennsylvania than in most states, which continue to adhere to a view of force as purely physical. And remarkably, in a handful of states, the use of significant physical force is required.

Compare this rather retrograde understanding to one that, in this past year, has ascended in colleges and universities around the country. On an estimated 1,500 campuses, rape is now defined not by force but by the absence of affirmatively expressed consent. For example, Yale’s definition of consent requires “positive, unambiguous, voluntary agreement at every point during a sexual encounter—the presence of an unequivocal ‘yes’ (verbal or otherwise), not just the absence of a ‘no.’” Similarly, at the University of Iowa, “consent must be freely and affirmatively communicated between both partners in order to participate in sexual activity or behavior. It can be expressed either by words or clear, unambiguous actions … Silence, lack of protest, or no resistance does not mean consent.”

Affirmative consent standards like these have quickly become the rule on campus. Whether the criminal law should move in this same direction—or instead to insist that the victim resist, physically or verbally—remains a subject of great controversy.

As lawmakers consider this option, it bears notice that a small number of states, including New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Vermont, have for decades required affirmative consent. In a recent paper, I surveyed the cases that have arisen in these states. I found that they tend to involve a passive victim: one who is either sleeping, fearful, or extremely intoxicated. Overall, the facts of these cases do not suggest a problem of “mixed signals”—an oft-cited basis for opposition to codifying affirmative consent. Indeed the cases tend to involve predatory behavior, not confusion. What we do see in the affirmative-consent jurisdictions is a formalized understanding that is—or is becoming—uncontroversial: a victim who is unconscious, sleeping, or immobilized by fright does not consent to intercourse simply by virtue of not resisting.

By her own account, Andrea Constand was passive. She could not move, could not see clearly, could not fully grasp what was happening to her. She did not express her non-consent. This fact was not lost on Bill Cosby. In his civil deposition, he explained his behavior as follows: “I don’t hear her say anything. And I don’t feel her say anything. And so I continue and I go into the area that is somewhere between permission and rejection. I am not stopped.”

Stripped of its more sensational facts, the Cosby case presents a scenario that will continue to recur: an individual who is “not stopped” and feels entitled to proceed. Whether the law endorses this behavior—that is, whether passivity is equated with consent or with its absence—is of tremendous importance.