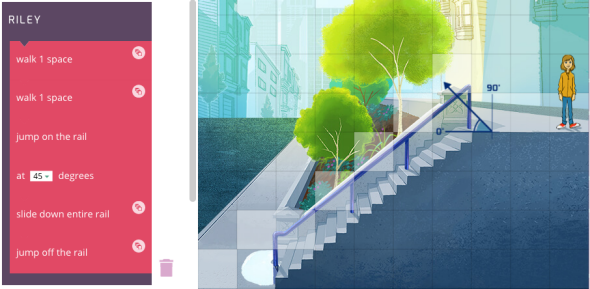

Kids who loved Inside Out can now code their own sequences for the film’s main character, Riley, to act out in a new online game from Google and Pixar. Users snap pre-programmed action commands into place to get Riley’s avatar to, say, slide down a banister or navigate a room littered with toys. It’s action-oriented enough to keep a child entertained, difficult enough to give her a sense of accomplishment, and remarkably similar to the format and syntax of actual programming code. It’s also made specifically for girls.

The three-level game is part of Google’s Made with Code initiative, which aims to nurture young girls’ interest in computer science through interactive coding projects and IRL events. Getting young girls into programming is one of the buzziest challenges the tech community has embraced in recent years—it’s spawned education programs like Black Girls Code and Girls Who Code, documentaries like Codegirl and CODE: Debugging the Gender Gap, and toys like GoldieBlox’s Ruby Rails, named for one of today’s most popular coding languages. High School Story, a popular app game that claims to have reached 30 percent of high-school girls in the U.S., just announced a new storyline about a young girl coder. Games are considered one of the easiest ways to target and attract girls to computer science: Most girls play games on their computers or phones, so the medium is frictionless and fun.

Some might protest, as they have with GoldieBlox, that Made with Code’s pink-and-purple color scheme and traditionally feminine subject matter, like designing a dress or accessorizing a selfie, solidify the same prescriptive stereotypes that limit girls’ career ambitions in the first place. But meeting girls where they’re at—a society with rigid gender norms—is a valid baby step toward an important end that doesn’t require first dismantling an entire set of assumptions. (When companies use these stereotypes in their STEM initiatives targeted at adult women, though, it’s a different story. See: IBM’s recent campaign to get women to hack a hairdryer.)

Will these games work? In a 2008 Australian study, high-school girls who chose not to take computer science courses said it was because the subject was uninteresting, they didn’t like computers, and the subject didn’t seem relevant to their future careers. Others have suggested that, in order for girls to achieve self-efficacy with computers—the idea that they can do something computer-related, and do it well, which encourages them to continue—the most important step is simply to do it, and do it well. Games that attract girls with themes and formats they already associate with fun, then gives them pathways to success, could address two of the top barriers to girls’ achievement in computer science.

But the more difficult stumbling blocks lay beyond girls’ self-perception. When girls look at the tech field and don’t see women, it stymies their sense of self-efficacy in computer science. The attitudes of the adults in their lives matter, too, and schools and parents are sending girls all manner of subtle and not-so-subtle cues that STEM careers are for boys. Meanwhile, for now, at least, men are the ones hiring programmers, promoting them to the top, and making boneheaded moves that keep women from feeling comfortable at tech events. Changing adult and male perceptions of women and their capacity in tech-related fields is just as important as changing the way young girls see themselves.

Behind many of these girl-coding endeavors lies a fear that women will miss out on a lucrative, fast-growing segment of the job market and that the future fruits of the tech sector—inventions that will shape the health care, education, communication, and entertainment of tomorrow’s world—will stem solely from men’s perspectives. The prevalence of men in STEM fields has led to such blunders as Clippy, the too-eager anthropomorphic paperclip of Microsoft Word, and crash-test dummies based only on an average man’s height and weight, which led car companies to tailor their safety features around test results that applied primarily to men.

If we want the best people in critical tech jobs, leaving out a sizable portion of the population is a losing bet. Games that encourage girls to see themselves in tech careers are an important development in tech education. But to change a tech industry that has become notorious for its sexist culture, boys’ perceptions matter, too.