For a procedure so common, there’s surprisingly little information about how, why, and where Cesarean sections are performed. Last year, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data placed the U.S. C-section rate at 32.2 percent, with a higher rate for women of color than for white women. The World Health Organization, meanwhile, stresses that doctors in many wealthier nations are performing unnecessary C-sections, which can put infants and the people birthing them at risk.

In April, the WHO reiterated its global target for C-section rates: 10 percent. Less than that, and maternal and infant mortality rates rise. More than that, and risks increase but mortality rates don’t improve. Accordingly, U.S. health officials hope to shrink the country’s C-section rate among women with low-risk pregnancies.

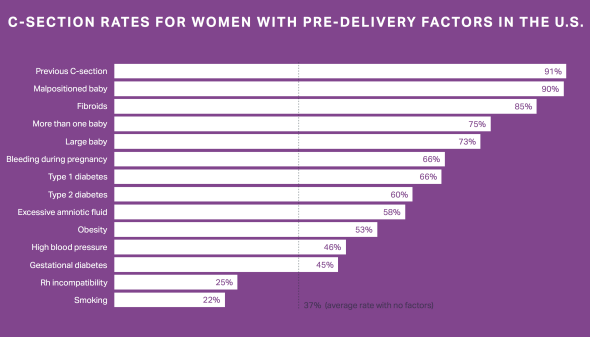

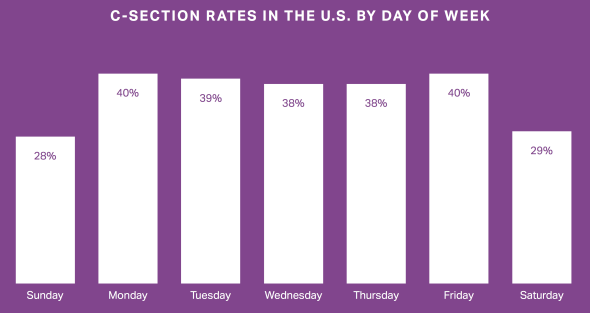

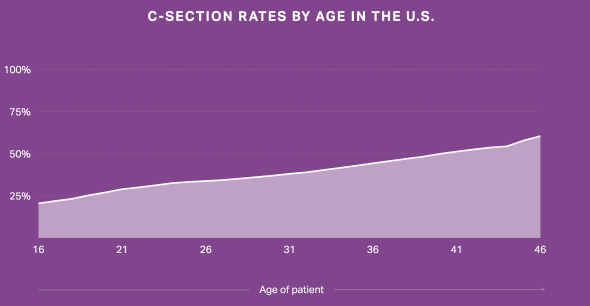

Patients now have a new tool to help them gather more information about potential doctors and ask better questions once they’re on the exam table. Amino, a company that runs a free site to help patients find and book an appointment with a doctor based on how many people with the patient’s given condition the doctor has treated, released a study yesterday that analyzes U.S. patients’ likelihood of getting a C-section. Using data from insurance claims from 4.4 million deliveries between 2010 and 2015—that’s 3.5 million people who’ve given birth, and about 22.6 percent of all U.S. births—Amino examined the medical conditions that are likely to lead to a C-section and sorted the C-section rate by the day of the week and patients’ age and geographic location.

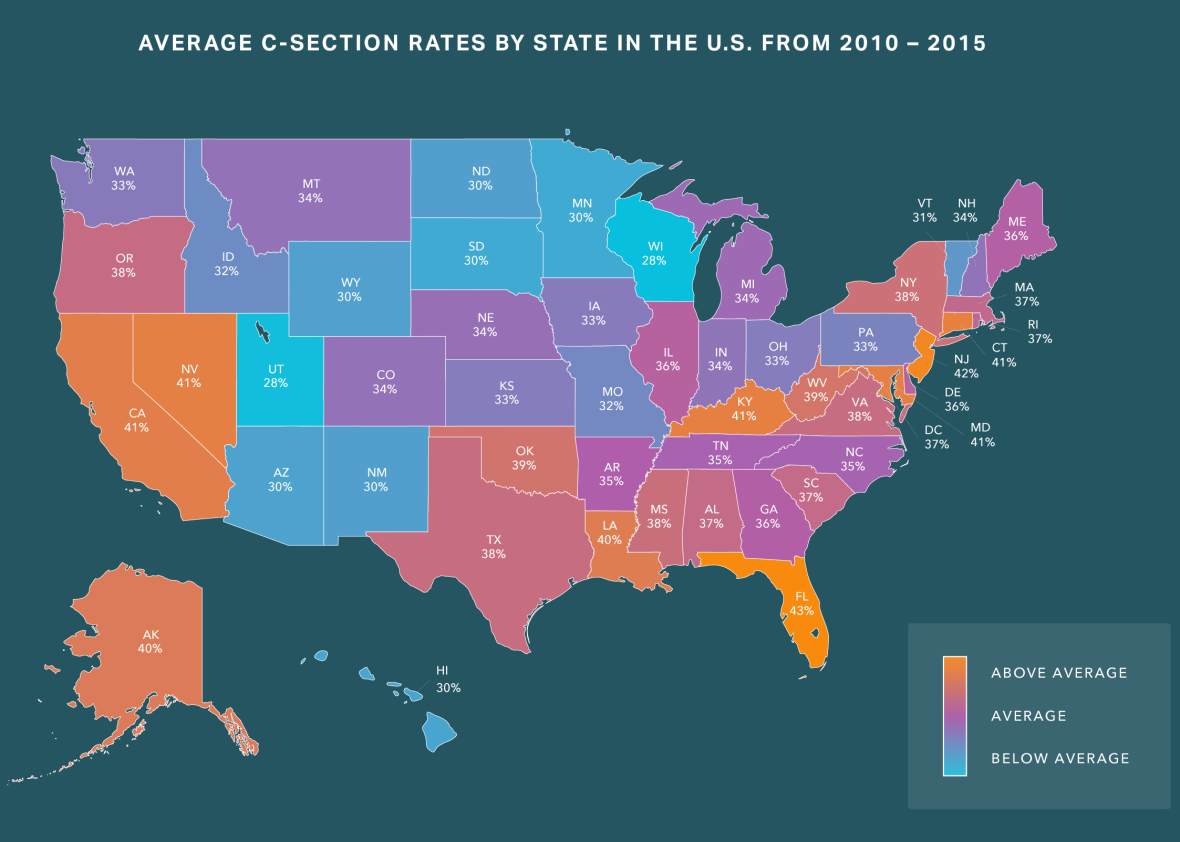

Courtesy of Amino

Courtesy of Amino

Courtesy of Amino

The interactive map Amino’s created shows a few clear hotspots for C-sections: Florida has the nation’s highest rate, 42.8 percent, with New Jersey not far behind at 42.3 percent. Wisconsin has the lowest C-section rate in the U.S.: 20.8 percent, more than 7 points below the next lowest state, Utah. Here’s how the study explains the wide discrepancy between states:

A woman’s ethnicity, race, culture, and socioeconomic status all might affect her chance of having a C-section. There are also staff practices at hospitals that can affect childbirth outcomes. For example, one recent study shows that 24-hour on-call obstetricians and availability of midwifery care may lead to a lower rate of C-sections.

Amino has also built a C-section predictor, which takes in information about a pregnant patient’s age, location, history of C-sections, pregnancy complications, and medical history, compares it to data collected from the 4.4 million deliveries, then spouts out the patient’s likely chance of getting a C-section.

In most pregnancies, the decisions surrounding a C-section don’t stem from the patient—a 2013 third-party report from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists found that “elective” or “maternal request” C-sections only accounted for 2.5 percent of all U.S. births. This new information could help empower pregnant patients to assess their own needs and risks, giving them a leg up in discussions with their doctors.