Last night, former Gawker writer Dayna Evans published “On Gawker’s Problem with Women” in Matter. Through a close read of a recent oral history of the site and interviews with former and current employees, Evans chronicles indignities both micro and macro. There were the incessant rape gifs in Jezebel comment threads that Gawker refused to address. There were dismissive comments, few women in leadership roles, and editors who threw the good scoops to male writers, who subsequently earned more money and public acclaim.

Evans’ piece in Medium exposes a few inequities that aren’t limited to Gawker. The gender wage gap is, of course, a nationwide phenomenon that doesn’t rest entirely on one-off discriminatory behavior. Employees are often paid based on previous salaries and their willingness to negotiate; while men benefit handily from kinder perceptions of their hardball negotiating, many hiring managers just want to pay out as little as possible for the best talent. And the leadership pipeline that Evans describes—where women are shunted into managerial editing roles that require some of a publication’s hardest, most thankless work—is a pervasive dynamic in an industry that produces a disproportionate number of male bylines and male top editors. Ditto Gawker’s lack of racial diversity.

But the sniping, backstabbing culture Evans depicts is unique to Gawker, and despite Evans’ thesis, it’s perpetuated by the company’s women, too. A comment on the article names several instances of women writers and editors lobbing mean-spirited blog posts at other women who did nothing to deserve a public shaming. Women writers linked to hacked nude photos of women celebrities—a hallmark of Gawker’s editorial strategy—on multiple occasions; Evans herself sent a boatload of traffic to the shameful “fappening” photos on 4chan last year. Natasha Vargas-Cooper used emails unearthed in the Sony hack to mock the “crotch-intensive” personal hygiene products purchased by former Sony head Amy Pascal. Maureen O’Connor negotiated for nonconsensual nude photos with a creepy celebrity stalker.

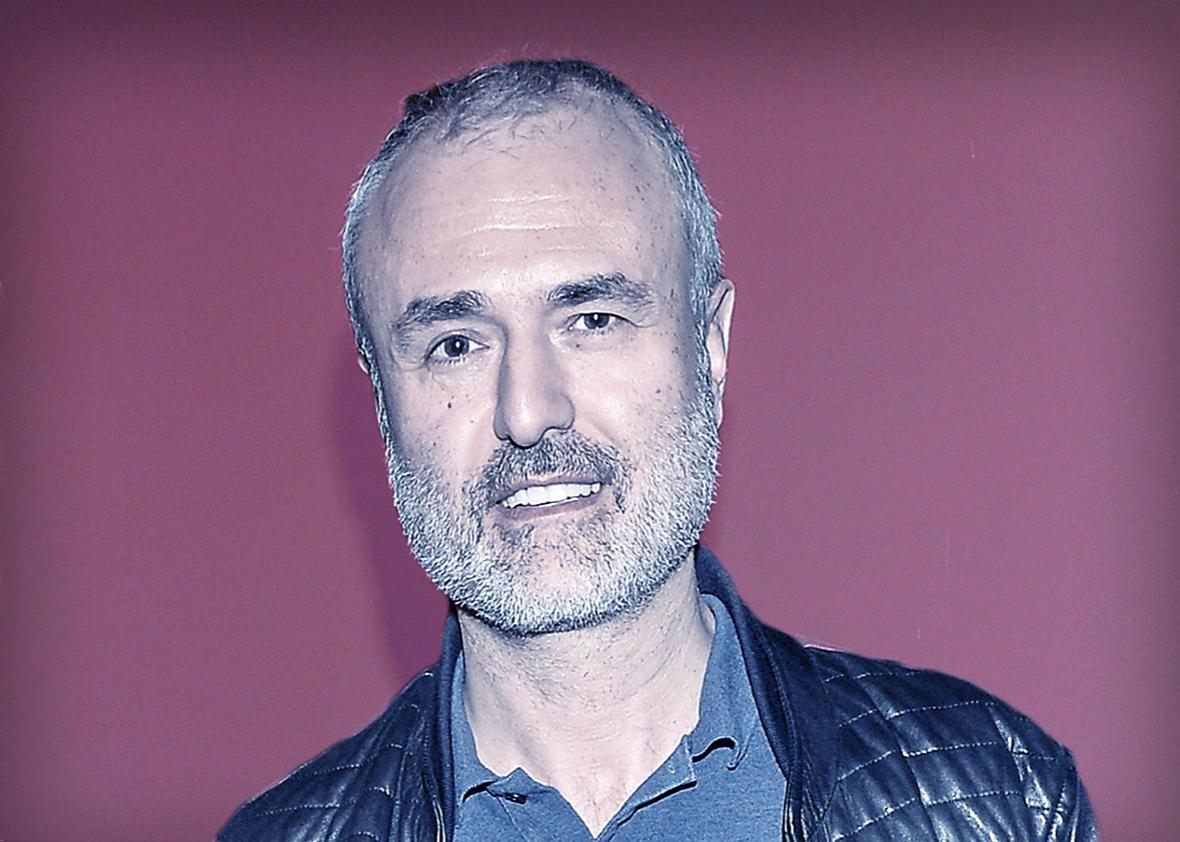

It’s impossible to extricate the will of the writer from the directives of the mostly male Gawker leadership, but it’s safe to say that the men of Gawker—including founder Nick Denton—weren’t the only ones nurturing a culture that exploited women in decidedly misogynist ways for traffic. Gawker’s business model rewards the kind of salacious, ethically questionable stories that are particularly harmful to women in the public eye. In Carla Blumenkranz’s n+1 assessment of Gawker from 2002 to 2007, she places some of the blame on former editor Jessica Coen:

Gawker had always sold itself as mean but it now became, actually, very mean. [Former editor Choire] Sicha, who liked to pretend to be a news organization, had sent “correspondents” and “interns” to official media events. Coen found more of them, and she sent them not only to launches and readings but also to private parties, where they took embarrassing party photos. This was the important development: the decision to treat every subject, known or unknown, in public or private situations, with the fascinated ill will that tabloid magazines have for their subjects.

On Twitter today, journalist Melody Kramer shared an old email she received during Coen’s tenure after applying for a Gawker internship in 2005. In the response she received, someone writing from the email address Jessica@gawker.com invited Kramer and another female applicant to “formally be my bitches” along with the other “editorial punkins.” At 20 years old, Kramer tells me, she just wrote it off as “bizarro.” Now, she thinks it’s “completely inappropriate.”

In her Medium article, Evans relates an anecdote from 2008, when the New York Times Magazine was set to publish a personal essay from former Gawker writer Emily Gould.

Days before the story — which would embarrass both Denton and the company — was published, Denton saw a video of Gould mimicking a blow job on a plastic tube and fed it to Gawker writer Andrew Krucoff to post. Even now, in 2015, while being interviewed for the Oral History, Denton remarked: “Why not? She’s a public person. I’m a public person. This was publicly available.”

That little phrase—why not?—is a neat sum-up of Gawker’s editorial philosophy. Shame that it’s so readily deployed against its female subjects, by men and women writers alike.