Two Princeton economists released a study on Monday that puts the United States’ recent spike in heroin and prescription drug overdoses in alarming perspective. Overall death rates among middle-aged white Americans are rising due to a huge jump in suicides and certain drug- and alcohol-related deaths, while at the same time falling in every other age group, racial or ethnic group, and wealthy nation in the world.

The study’s authors, Anne Case and Angus Deaton, a married couple, were each working on unrelated research projects when they hit upon this trend. Though deaths from suicides, accidental drug and alcohol poisonings, and liver diseases related to alcohol abuse are on the rise among all education groups in middle age, they’ve had a particularly detrimental effect on whites with a high school level education or less. In this education group, the mortality rate for whites aged 45 to 54 rose by 134 deaths per 100,000 people—from 602 to 736—between 1999 and 2013, enough to turn around the previous downward overall trend of mortality rates for the entire age and race group.

Over email, Deaton explained why the data surprised him, how this epidemic compares to the HIV/AIDS crisis, and why the study matters to discussions of income inequality. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

It sounds like you sort of stumbled across this discovery while looking at other data. How did that happen?

Anne was working on [researching] pain and morbidity, and I was working on suicide. At some point, I thought it would be useful to put the suicide data in the context of overall mortality, and did so in comparisons with other countries. We then immediately saw that the U.S. was doing very badly in this group, discovered the rising mortality rate, and saw that it could not all be suicides, though suicides contributed. So then we went through the causes of deaths, and found the poisonings. At first, we thought of cyanide, or accidentally drinking Drano, but then we realized what it was [alcohol and drugs].

What did you think to yourself when you first noticed the trend?

That it surely must be wrong! We spent an enormous amount of time going over the data over and over, and checking and triangulating it.

You told the New York Times that HIV/AIDS is the only good analogue as far as these death rates go. Can you expand on that comparison?

We calculated that about 500,000 middle-age Americans died who would still be alive. AIDS has killed more than that but the numbers are in the same ballpark. The comparison is useful because people have a hard time thinking about changes in mortality rates—so many per 100,000. And everyone knows about HIV/AIDS: People wear ribbons and it is seen as a national tragedy. But there are no ribbons, no awareness for this, and there should be.

In the study, you present a few possible reasons for the climb in morbidity, including the fact that middle-aged people are experiencing more chronic pain than in previous years, which could lead to suicide or drug abuse. What implications could this study have on discussions of U.S. health care?

I am not sure this has much to do with health care. Addiction is very hard to treat, and it is not clear that insurance, even with the extension to mental health, is helping as much as it can.

This paper could contribute to conversations on income inequality, too, considering that suicide rates have gone up among poor Americans as their real income has fallen.

Yes, I hope so. We already know that income gaps are widening between better-educated and less-educated people. This study says the people with low incomes are losing out not only on income, but also on health.

Did you look at any regional data breakdowns within the U.S.?

There are broad regional patterns in the paper. It is not so easy to break down the increase in deaths by state and education, [though], and it is a colossal amount of work. We do know that some of the patterns of self-reported morbidity worsening in middle-age are increasing in the same way in every one of the 50 states.

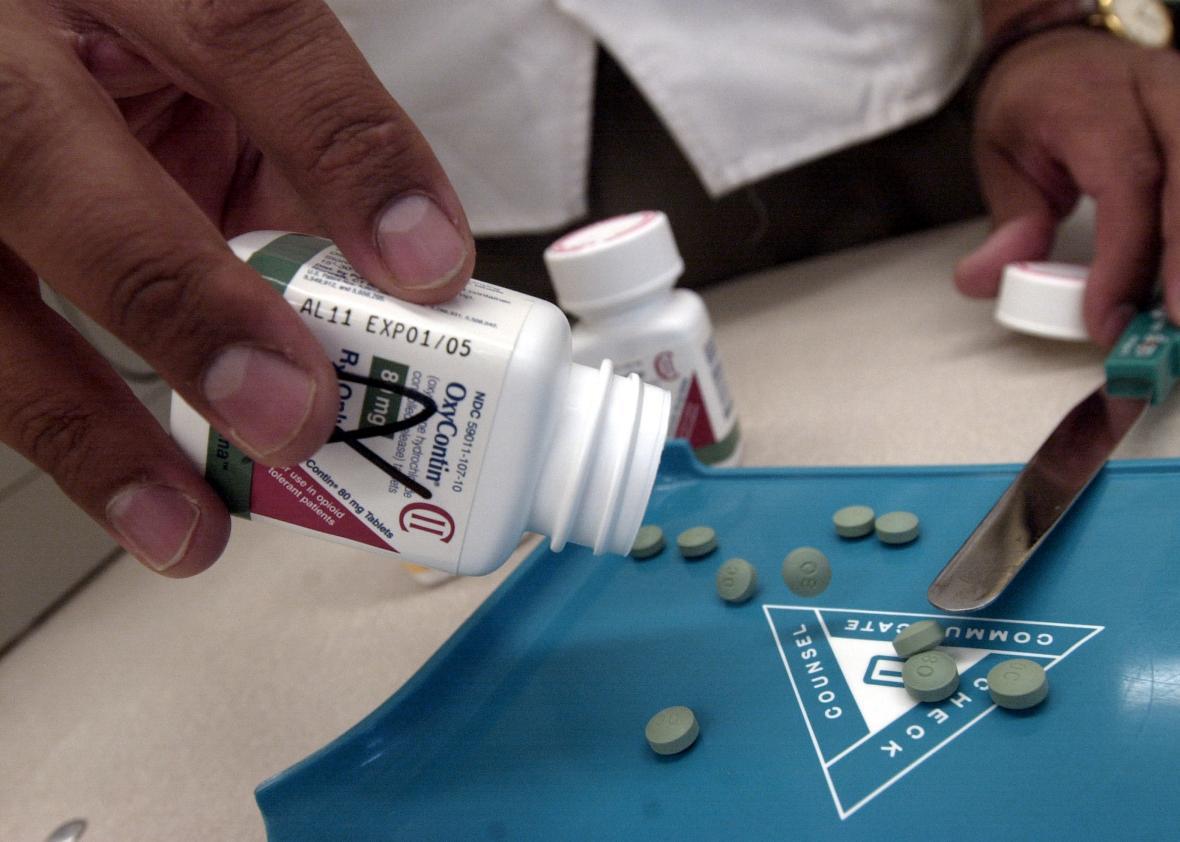

Why did you combine alcohol poisoning with drug overdoses, and heroin with prescription opioids, in your data analyses?

It seems sensible to put all of the accidental poisonings together. Also, some of the literature suggests than when people can’t get opioids, they turn to opiates. And alcohol is also a drug in a similar sense. But we grouped those with liver disease and with suicide because drinking and drugging can all be thought of as ways of killing yourself, just more slowly than with a gun.

Rising death rates are troubling for the country at large, but many of the calls from white people for a kinder, gentler drug war and better drug treatment have only come after this enormous recent spike in opioid-related deaths. What do you make of the fact that this study may finally get white people to pay attention to how the U.S. treats people who are addicted to drugs?

There is a famous history of drugs and drug policy on opiates in the U.S. by David Courtwright called Dark Paradise, which notes that how America treats opiates (and opioids) has always depended on who are the users: rich or poor, black or white, educated or not. So what we are seeing now, with a kinder gentler war as addiction moves from blacks to whites, has happened before.