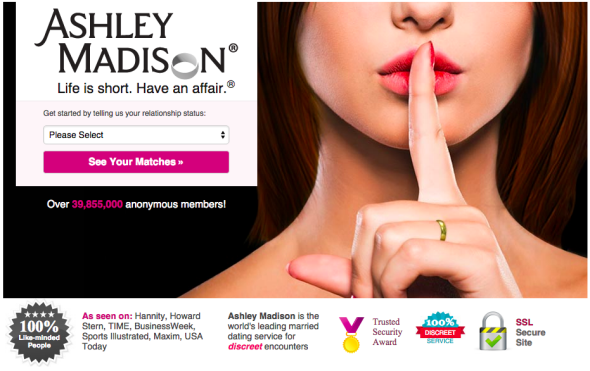

Here’s a safe bet: If your husband’s name turned up in the Ashley Madison data released by the hacker group Impact Team, he probably isn’t cheating on you.

While Ashley Madison claims to have almost 40 million members, very few of them seem to have gotten much out of the site. Studying internal emails from the company’s management, Gizmodo’s Annalee Newitz claims to have “found ample evidence that the company was actively paying people to create fake profiles.” And many of the profiles created by real women, Newitz argues, were inactive. If this is true, the site’s male users—who Newitz reports had to pay to send “custom messages” to women—were essentially talking to themselves. Above all else, they’re a pitiable bunch, but that fact is unlikely to spare them from the ongoing parade of public shaming—as well as the threats of extortion and identity theft—indiscriminately directed at those implicated in the leak.

The lucky users were those who got out before getting trapped, though even they are feeling the heat. In this week’s “Dear Prudence” advice column, a married reader wrote in claiming to have created his account when he was “single, bored, and curious,” adding, “I surfed the site for an hour or two, and didn’t contact anyone.” Because the site never purged the data of former users, even those who paid to be removed, his information was still there.

It’s possible that Prudie’s correspondent was just covering his ass, but if he’s telling the truth, he’s not alone. Few if any of the site’s male users were successfully employing it to set up extramarital affairs. According to Newitz, about two-thirds of the site’s male users—slightly more than 20 million men—had checked their messages at some point after creating their accounts. But only 1,492 women had looked at theirs. Whether or not real women were logging on to the site, Newitz argues, their accounts “were not created by women wanting to hook up with married men. They were static profiles full of dead data.” Unless the men were all chatting up one another—unlikely given the site’s almost compulsory heterosexual framing—the messaging stats suggest that relatively few visitors were engaged in real correspondence.

If hardly anyone was successfully using the site for its ostensible purpose, the primary line of attack against those found on its hacked user lists—that they’re actually cheaters—starts to seem dubious. Troy Hunt, who maintains a site that lets people check whether their information has been compromised on the Internet, has compiled a list of reactions to the hack from his commenters. “I’m glad someone is providing some true justice in the world,” goes one typical response. Another reads: “Anyone who signed up to this sick site deserves everything they have coming to them.” In their minds, just having an account is an Old Testament–level offense.

But even if millions of men who joined the site did so in pursuit of real infidelity, they did not, for the most part, achieve it—at least not via Ashley Madison. Any explanation of what made them sign up—even the marginally famous like Josh Duggar—is bound to be speculative at best. Ultimately, the site gave such users little more than the idea of adultery, what Dear Prudence’s Emily Yoffe called a desire “not to actually get into bed with strangers, but to imagine what it would be like to do so.”

Whatever their original intentions when they created their accounts, most of Ashley Madison’s members committed little more than thought crimes. Sure, they may have taken those thoughts one step further by signing up for a cheating site, but that, in and of itself, tells us nothing about their marriages. Condemning acts of the imagination is a familiarly dark path. It encourages us to pathologize ordinary proclivities, such as porn consumption, to justify our contempt for harmless behaviors. Yet, by and large, most of us know and accept that fantasies are just fantasies, and the evidence that Ashley Madison is ultimately a bust may not be all that surprising. Newitz’s revelations should stop all the finger-pointing and public bounty hunting, but it doesn’t seem likely that they will. The men who either dabbled briefly or chased after make-believe visions in Ashley Madison will always be branded by their time on the site.

Perhaps that’s because the Internet itself has irreversibly blurred the lines between real and fake, life and dream. Anonymity—or at least the illusion of it—can bring out the worst in us, giving us permission to behave in ways that we never would if we knew we could be identified. One view of human nature would say that when we behave badly on the Internet, free of society’s strictures, we are more fully ourselves. According to this increasingly common conceit, even a whiff of the unseemly online seems to guarantee real awfulness.

It’s not just old-fashioned moralism, then, that inspires us to wag our fingers at the victims of the Ashley Madison hack. Instead, it’s the way that the Internet tricks us into qualifying fantasy as fact. As Newitz’s research shows, the men most dedicated to the site suffered from this firsthand. We, however, would do well to remember the distinction. In the end, Ashley Madison was a haven not for sinister cheaters, but gullible dreamers. And now they’ve had their rude awakening. Let’s go easy on them until they have their coffee.